Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Williams Selyem: Pinot Noir Allen Vineyard 1987–2016

BY STEPHEN TANZER | JUNE 21, 2018

Whether a grand cru or a fine premier cru, Williams Selyem’s second flagship Pinot has established a 30-year record for individuality, longevity and consistency.

Back in the late 1980s, the earliest vintages of Williams Selyem Pinot Noir caught the attention of Burgundy lovers for their succulence and sweetness, as well as for their complex balance of sappy fruits, soil tones, spices and flowers, and their considerable early allure. I recall being blown away by the 1987 Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Pinot, which I considered to be the sexiest New World Pinot I had tasted up until then, with the possible exception of the 1985 Ponzi Vineyards Pinot Noir, a wine that had memorably been preferred by a group of my Burgundy-loving friends in the late ‘90s in a blind flight with 1985 Morey-Saint-Denis grand crus from Ponsot, Dujac and Domaine des Chézeaux.

Allen Vineyard, with fog over Russian River

If there was ever a fear expressed by early buyers of the Williams Selyem Pinots, it was that the wines tasted so good early on that people wondered whether they could possibly age. As it turned out, these worries were unfounded. About a dozen years ago, I conducted a tasting of all of the vintages made by now-legendary winemaker Burt Williams from the original Rochioli Vineyard vines (1985 through 1997). The wines showed spectacularly and were full of life. Introduced with the 1987 vintage, the Allen Vineyard Pinot Noir was the second flagship Pinot in the Williams Selyem range. My experience with the Allen Pinot also dates back to its maiden vintage. This March, the winery and current winemaker Jeff Mangahas staged a spectacular vertical tasting back to vintage 1989 of the Allen Vineyard for me. I was able to complete the vertical by pulling the first two vintages from my own cellar. So, this time around, I tasted Pinots dating back a full 30 years.

Williams-Selyem's new winery

The Origins of Allen Vineyard

Fourth-generation Californian and real estate developer Howard Allen, who already owned a small vineyard in Oakville, came to the Russian River Valley in 1970 because he thought it would be an ideal place to grow Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. There were barely any Pinot Noir vines in Sonoma County back then, with a few notable exceptions like Rochioli Vineyards, farmed by trailblazer Joe Rochioli, whose early-‘80s vintages were made by Gary Farrell, and Dehlinger Winery, with the wines then made by Fred Scherrer. Allen purchased a block of land adjacent to Rochioli Vineyard and planted it in 1974, using cuttings from Rochioli Vineyard’s West Block; at the time these were referred to as old Wente selections but they quickly became known as Rochioli selections, as the West Block essentially became the “mother block” for subsequent Pinot Noir plantings in Russian River Valley. The land Allen bought is mostly on the western, hilly side of Westside Road, in a spot where, as it turned out, acidity levels in the grapes remained sound even as sugars increased (previously the site’s lower, flatter section had been the home of a prune orchard, and sheep grazed on the hillside). The soil at Allen Vineyard is mostly pebbles, river rock and dark loam with streaks of red clay, while Rochioli Vineyard, which is across Westside Road along the Russian River, features a lot of loam over 50 feet of gravel.

Beginning in 1980, Allen started selling some of his fruit to Burt Williams, then a garage winemaker with his partner Ed Selyem. Burt and Ed, as they were widely referred to by their customers, officially established their Hacienda del Rio winery in 1981, but in short order re-named their operation Williams & Selyem after receiving a cease-and-desist order from Hacienda Winery. The first vineyard-designated Pinot Noir released by Williams Selyem was the 1985 Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir. It was followed two years later by the Allen Vineyard Pinot. In 1989, the Williams Selyem operation leased an old barn adjacent to Allen Vineyard and turned it into a low-tech winery. As the Williams Selyem wines in the late ‘80s received rave reviews, the winery quickly developed a cult following. Demand soon outstripped supply, so much so that by the mid-‘90s there was a two-year wait to get on the mailing list.

Williams Selyem's new Estate Vineyard (formerly Litton Estate Vineyard)

Winemaking Has Never Strayed Far from Burt’s Original Formula

I recently managed to track down Burt Williams, now retired and living in Santa Barbara, and quizzed him about the ancient history of his Allen Vineyard Pinot. My first question was whether he was trying from day one to make wines that would reward extended cellaring or whether they were intended more for early consumption. His response: “I was just trying to make balanced wines that showed where they came from and the vintage character. I never gave any thought to preservation.” In fact, Williams made very limited use of sulfur products, and he did not pump, fine or filter his wines. A key to the Allen Vineyard’s quality is that the vines are nearly always harvested quickly in late August (Mangahas noted that Williams Selyem’s 4.4 acres of Pinot Noir – out of a total of 9.2 – are brought in within one or two days). Yields have always been extremely low – typically between a ton and a ton-and-a-half of fruit per acre in recent years – and annual production of the Allen Vineyard Pinot is normally in the range of 350 to 400 cases. Williams told me that he picked by taste “but also with a healthy pH,” as he didn’t want to make flabby wines.

Williams used foot treading to get the juice out of the berries (he normally retained about 33% whole clusters until 1991, then about 25% thereafter – “whatever was necessary flavor-wise and tannin-wise”), and began with a pre-fermentation cold soak lasting five or six days, using dry ice. Despite the cold maceration, the wines were never particularly dark, with the possible exception of the 1998 Allen, which was made from a drought vintage that featured very small berries. Williams then carried out about four daily punch-downs of the cap during a week of fermentation before taking the wines straight to barrels without any further post-fermentation maceration. At some point during the early years, Williams began to add small amounts of acidity during the fermentation in years when he thought it was needed, noting that the added acid mostly dropped out of the wines but had a salutary effect on pHs.

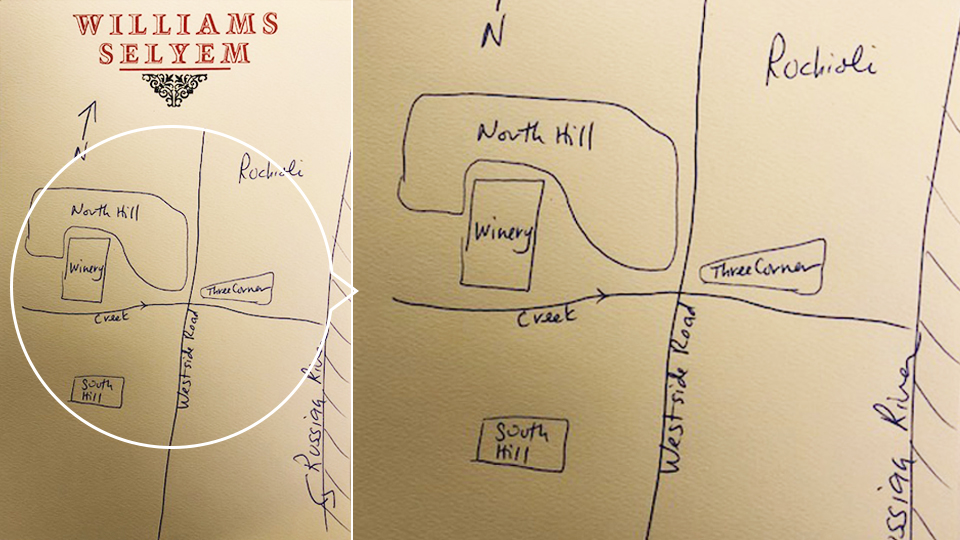

Winemaker rendering: Jeff Mangahas’ sketch of Allen and Rochioli Vineyards, not drawn to scale

From the start Williams aged the Allen Vineyard Pinot Noir in about one-third new oak – all Tronçais “toast of the house” (i.e., medium-plus) barrels from François Frères. The wines were racked just twice: in early spring and prior to the bottling, which normally took place the second December or January. He upped the percentage of new oak to 50% beginning in 1990.

There have been just two winemakers at Williams Selyem since Burt and Ed sold their winery in 1998 to John Dyson, who owned Millbrook Winery in New York’s Hudson Valley and had also been a long-time customer for the Williams Selyem wines. Bob Cabral, who had previously made wine at Hartford Court, took over winemaking duties in 1999 and was responsible for vinification through vintage 2013. (Williams stayed on for a year as a consultant, then left to purchase his Morning Dew property in Anderson Valley in 2000). Mangahas, who had also previously been winemaker at Hartford Court from 2006 through 2010, was hired by Williams Selyem in 2011 and took over as head winemaker when Cabral left after vinifying the 2013 harvest.

Three decades of Williams Selyem Allen Vineyard Pinot Noir

The Allen Vineyard Pinot Noir Over the Years and Now

The original Allen Vineyard was essentially divided into a northern section and a southern section (referred to by the winery as North Hill and South Hill), plus a third parcel that was variously known as Three Corner or Tri-Corner. This latter section was located just next to Rochioli Vineyard on the east side of Westside Road. After the 1996 harvest, Howard Allen gave the Three Corner parcel to his old friend Joe Rochioli and the old vines were no longer available to Williams Selyem. Some new vines were planted in Allen Vineyard in 1996, and a couple years later a tiny bit of clone 115 was planted in the southern part of the vineyard. But even today, fully two-thirds of Williams Selyem’s Allen bottling is from the old vines planted in the early ‘70s.

Mangahas’s approach to harvesting, winemaking and élevage appears to be a closer match to Williams’s original techniques than was Bob Cabral’s. Cabral typically picked a bit later, for fuller ripeness, at least during the first half of his tenure. He also raised the percentage of new oak for the Allen bottling from 60% to 70%. Mangahas has consciously been harvesting a bit earlier and using less new oak (now back to 50%), and today the winery uses barrels air-dried for two years, rather than the three years that Williams preferred. Since 2011, the wines have been raised and bottled at the Williams Selyem’s new facility, which is located less than a mile south of Allen Vineyard in the middle of their new Williams Selyem Estate Vineyard (previously called Litton Estate, as the property was purchased in 2001 from the descendants of Cecil and Luella Litton), but the crush and vinification continue to be done at the old barn.

Most of the early vintages in my tasting were fully mature but the best of them still retained considerable fruit character and appeal. In a few wines I was particularly struck by a captivating juxtaposition of evolved balsamic and even maderized notes and still-lively red fruits. (Of course, I must note that the wines I tasted at Williams Selyem have almost certainly been kept in near-perfect conditions through the years, and my samples of the ’87 and ’88 came from steady 55-degree storage). While wines from Rochioli Vineyard are characterized by blacker fruit character, typically fuller body and robust tannin structure (the wines frequently take a bit longer to open than the Allen), Allen Vineyard is more about red fruits, minerals, spices and flowers; it’s normally more delicate than the Rochioli, although Mangahas noted that Rochioli, despite having “a bigger tannin profile,” typically shows more refined tannins owing to more homogeneous tannin ripeness.

I have long considered Rochioli Vineyard to be an undisputed grand cru for California Pinot Noir. On that scale, Allen would rate as an exceptionally fine premier cru, on the order of a Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses or Gevrey-Chambertin Clos Saint-Jacques. But that’s a debate for another day.

See all the wines in the order tasted

You Might Also Enjoy

Turley Zinfandel Hayne Vineyard: 1993 – 2015, Stephen Tanzer, May 2018

Vintage Retrospective: The 2008 Napa Valley Cabernets, Stephen Tanzer, May 2018

O’Shaughnessy: Cabernet Sauvignon Estate Howell Mountain 2000 – 2015, Stephen Tanzer, April 2018

Crocker & Starr Cabernet Sauvignon Stone Place: 1999 – 2015, Stephen Tanzer, April 2018

Vineyard 29 Estate Cabernet Sauvignon Retrospective, Stephen Tanzer, April 2018

Vintage Retrospective: The 1997 Napa Valley Cabernets, Stephen Tanzer, September 2017

Verticals of Ramey’s Hyde and Ritchie Vineyard Chardonnays, Stephen Tanzer, July 2017