Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Book Excerpt: A Brief

History of Napa Valley, Part II

SURVIVING PROHIBITION & THE RECOVERY YEARS, 1920–1959

In the American imagination, the 1920s were a boozy, riotous era when flapper girls and gangsters commingled in underground speakeasies. While the extent of this licentiousness is likely exaggerated, one thing is certain: all that wickedness was born of Prohibition, a legislative attempt to promote sobriety and lawfulness. Ironically, liquor consumption actually increased during the “dry years,” and many illicit fortunes were made in its trade. The same cannot be said for the wine industry, however: Prohibition was a nearly fatal blow. Those few wineries that survived, like Beaulieu Vineyards and Beringer, did so mainly through religious or medicinal contracts, the only legal channels for wine production at the time.

Grape growers fared slightly better than winemakers. A provision in the Amendment allowed every household to produce 200 gallons of fruit juice a year; while the wording was clear that the juice must be “non-intoxicating,” this small allowance effectively served as a license for home winemaking. Growers were able to save their vineyards by selling fresh grapes, or grape concentrate, to home winemakers all over the country. However, the often arduous journey via railcar proved problematic for most grape types, and vineyard compositions shifted to favor heartier, thicker-skinned varieties that could better survive such a trip. These “shipper varieties” were almost always red, though Muscat of Alexandria was a popular white. Growers hastily grafted over or replanted to these varieties, often interplanting the different grapes within the same plots. These jumbled plantings became known as “mixed blacks,” and the scattered sites that remain today are among the oldest producing vineyards in California. By 1926, the vineyard breakdown for Napa Valley was 40 percent Alicante Bouschet, 30 percent Petite Sirah, 16 percent Zinfandel, 13 percent Carignane, and 1 percent everything else. Almost all of the premium varieties favored in the 1890s had disappeared.

When Prohibition was repealed in December 1933,

the wineries of Napa Valley were in serious disrepair, the vineyards were

planted to pedestrian varieties, and America was in the throes of the Great

Depression. Nonetheless, many moved to capitalize on the newly liberated market

for wine—old wineries coughed back to life, releasing what little inventory

they had managed to retain, and newcomers scrambled, fast-forwarding through

many of the steps necessary for the creation of fine wine. The result was a

disaster. Much of the wine that hit the market following Repeal was made of

inferior grape types and crafted with antiquated, faulty equipment. The best

was merely poor in quality, the worst completely biologically unstable; all of

it did little to endear a thirsty country to its national product.

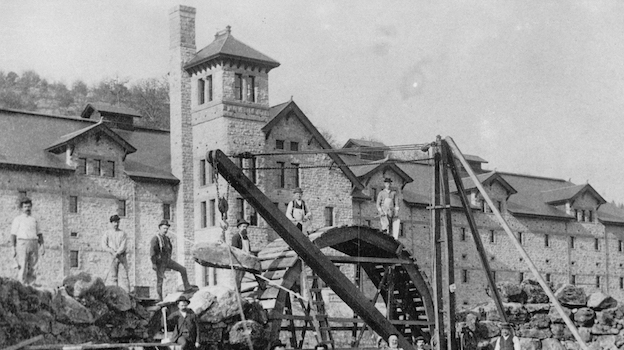

Greystone circa 1900. Upon its completion, Greystone was the largest stone winery in the world.

Quality advocacy became the buzzwords of the

day. Esteemed wine critic Frank Schoonmaker began campaigning for regional and

varietal information to be advertised on labels. UC Davis started taking on a

more proactive, advisory role within the winemaking community, largely through

the work of professors A. J. Winkler and Maynard Amerine. Even the government

stepped in, establishing some basic standards for table wine production, such

as the restriction of chaptalization, and the setting of upper limits on

volatile acidity and lower limits on total acidity. Equally important were the

efforts of a frustrated Georges de Latour, owner of Beaulieu Vineyards, who

through his connections to the clergy was uniquely poised to profit after

Repeal, only to see all his wine rejected as unsuitable. De Latour knew he

needed a proper winemaker, preferably with a background in chemistry, and set

off to France to find one. He returned in 1938 with the Russian Andre

Tchelistcheff, a man who would prove crucial to the future of American wine.

But beyond the immediate quality concerns lurked another, perhaps greater stumbling block to Napa’s return to glory. It can be argued that the biggest victim of Prohibition was the American palate. In the 1920s, American cooking underwent a serious transformation: kitchens shrank, canned food was the latest craze, and the rise of soda pop after World War I had given America a sweet tooth. By the time of Repeal, wine had long been eradicated from the dining table, and those that had continued to drink it during the dry years were now accustomed to the crude, homemade brew of their neighbors. Fortified and sweet wines were the new preferred styles, often sold under purloined European monikers. The wineries of California released a slew of sherries, ports and other “stickies”; more than one winery even offered a “Château d’Yquem.”

The restoration of Napa Valley to a center of quality table wine production was a long, slow process, tackled by a stalwart few. The majority of activity in the 1930s surrounded the reopening of closed wineries, such as Inglenook, Beringer, and Larkmead, along with the arrival of some very important newcomers. Louis M. Martini moved his winemaking operations to St. Helena in 1932 (just prior to Repeal), and the Mondavi family purchased the Sunny St. Helena winery in 1937. The 1940s also saw a handful of key players enter the arena. Freemark Abbey, Lee Stewart’s Souverain, Stony Hill, and Mayacamas were all freshly founded this decade, and old edifices breathed new life with the Mondavi family’s 1943 purchase of Charles Krug and the Trinchero family’s 1946 purchase of the old Sutter Home estate.

World War II played a consequential role in Napa’s revival. European wines became increasingly difficult to import, and the resulting demand for domestic products helped many of the Napa wineries regain some lost footing in the market. Eastern distributors were compelled to look to California when their French supplies ran out, which begat relationships that survived well beyond wartime. World War II also forced many wineries to begin estate bottling, as the shipping of casks of wine to East Coast bottlers became impossible when the rail cars that carried them were commandeered for military purposes. Estate bottling drastically improved the quality of much of Napa’s wine, and allowed the wineries greater control over not only their finished product, but also their branding and marketing.

After the war, and throughout the 1950s, Napa Valley continued to inch forward. Internally, Andre Tchelistcheff canvassed the valley, encouraging the planting of better varieties in better places, as well as improved winemaking techniques. Beyond Napa, a young and irrepressible Robert Mondavi traveled the country on behalf of the Charles Krug winery, endlessly campaigning for fine wine in general, and fine wine from Napa in particular. This resilient collection of individuals and estates could hardly guess that all their tireless efforts were close to paying off. The slow progress of the three decades since Repeal was about to reach a tipping point. The renown of Napa Valley was poised to soar.

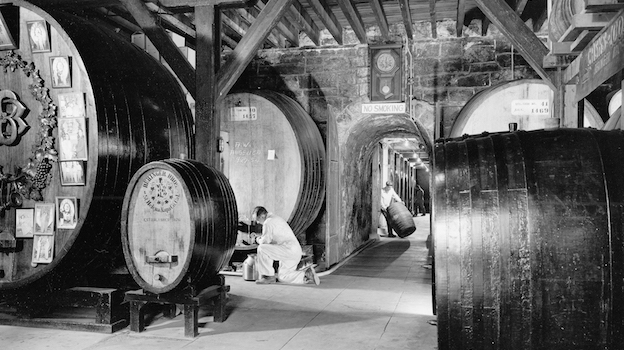

Interior shot of Beringer's winery in 1954.

GROWTH SPURT THROUGH THE JUDGMENT OF PARIS, 1960–1976

The 1960s were a period of enormous growth for Napa. At the decade’s open there were only around 10,000 acres of vines in the county—still less than half of the 1891 acreage, and only 6 percent of that total was dedicated to Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir combined. But both figures would change rapidly as vineyard acreage exploded, most of it dedicated to premium varieties. The interest of outside investment in Napa Valley intensified during the 1960s, mirroring Americans’ growing taste for fine wine. A critical victory for the California wine industry came in 1967—the first year in which table wine beat fortified wine sales in the United States, as well as the year that annual per capita consumption topped one gallon. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what caused the shift in domestic appetite—some credit a rising American affluence, some posit that the growing ease of jet travel was exposing more Americans to European customs, and certainly the growing appreciation for French cooking as championed by Julia Child had furthered the cause. However you explain it, it was good news for fine wine. More wine drinkers could support more wine producers, and those as-yet unfounded wine producers were about to storm the gates.

The decade of the 1960s can boast of the birth

of several wineries and one very decisive death. In 1964, John Daniel, Jr. sold

his family estate, Inglenook, to corporate interests. In a few short years, the

reputation of Inglenook, considered by many to be Napa’s crown jewel, was

destroyed. But this rain cloud over the Valley could not overshadow all the

positive happenings. Many of today’s best wineries got their start in the

1960s. Names like Heitz, Chappellet, Sterling, Spring Mountain Vineyard, and

Robert Mondavi all set up shop during this remarkable decade. Importantly, many

of these new wineries would take a good long look at Cabernet Sauvignon as the

key to quality. Also of critical importance to the future of Napa Valley was the

creation of the Agricultural Preserve. In 1968, Napa County made history when

it enacted legislature that would safeguard 26,000 acres (now 38,000) of valley

floor and foothills for either agriculture or open space use, thereby

preventing unchecked development. Though this ruling was quite controversial at

the time, today it is widely regarded as a triumph of green over greed, and

marks the beginning of a series of landmark environmental achievements for Napa

Valley.

The 1970s saw another swell of newcomers to the valley. Many of the wineries that formed in the first half of the decade remain among Napa’s most illustrious: Diamond Creek, Clos du Val, Silver Oak, Caymus, Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, Stags’ Leap Winery, and Joseph Phelps. The people behind these brands were inspired by the achievements of those that came before them, and had moved their families (and often their fortunes) to Napa in the hopes of joining the party. Though by now there were several dozen wineries in the Valley, life in Napa remained agricultural, remote. The lifestyle was pastoral but it was also gritty. The decision to found a winery was still largely an act of optimism mixed with folly. And while there was sage council available (Tchelistcheff, Mondavi, Amerine), a great deal of the work was speculative, and much of the success pure luck. And even if the stars aligned and great wine was produced, it still needed to be sold. Though an appreciation for fine wine was growing in the United States, California wines were still relatively unknown. And where they were known, they were often regarded as an anomaly, more of a curiosity than a serious contender. The 1976 Judgment of Paris changed all that.

Timed to coincide with the United States bicentennial, the Paris tasting was organized by British wine merchant Stephen Spurrier, who owned a wine shop in Paris. Spurrier traveled to California, selected what he deemed to be the Golden State’s best Cabernets and Chardonnays, and pitted them against some of France’s top wines in a blind competition scored by a panel of esteemed French wine professionals. The controversial results placed California in first place for both white and red, with the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay and the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars S.L.V. Cabernet Sauvignon. The tasting was witnessed by a single journalist, an American named George M. Taber, who covered the event for Time magazine in the June 1976 issue. The “article” was in fact a single column with no photograph, placed toward the back of the magazine. But despite its lowly positioning, enough of Time’s massive readership (20 million, composed largely of the American middle class) read the piece to cause a marked spike in California wine sales. Before long, the buzz surrounding this event built to a roar as other publications rebroadcast the results, spreading the good word. Though the tasting and its scoring has been relentlessly critiqued, in the eyes of many, this single event brought the wines of California into the international dialog.

Two Christian Brothers tasting wine

FROM THE FLOODGATES TO THE FLOOD, 1977–1989

The flow of fresh blood into the Valley positively surged after the Judgment of Paris. In the four years between 1978 and 1981, 46 new wineries opened. This list includes such luminaries as Duckhorn, Niebaum-Coppola, Grace Family Vineyard, Opus One, Shafer, Saintsbury, Frog’s Leap, and Far Niente. As a consequence of all this new production, planted vineyard land exploded, topping 25,000 acres by 1980. The new vines and wines were all established in the hopes of wooing a nation that was just warming up to the idea of wine drinking as an inextricable part of the good life.

The American middle class’s growing interest in

wine at this time was shaped in no small part by the efforts of Robert Parker’s

Wine Advocate and the Wine Spectator, founded in 1978 and ’79,

respectively. Both publications attempted to simplify the subject for a largely

uneducated populace, by fixing a wine’s worth to a simple numerical value.

Though the 100-point scale has been widely criticized, it cannot be emphasized

enough how empowering this seemingly simple and democratic system was to the

nation’s fledgling wine drinkers. Both magazines found a lot to love in Napa,

and the Valley’s place as California’s preeminent wine region grew ever more

irrefutable. The very word “Napa” began to act as a kind of implicit stamp of

approval, bearing all the same promises of quality as the embossed seal of a

luxury brand.

An important side note in this evolution is Napa Valley’s inaugural wine auction in 1981, a charity function that would grow to become the preeminent wine lifestyle event in the United States. Over the years, the auction would attract boundless celebrity and money to a region that was becoming increasingly glitzy. The rise of this event-turned-phenomenon perfectly encapsulates Napa’s shifting image from a humble agricultural outpost to a playground for the wealthy. In fact, Napa’s shiny veneer and the boom economy worked to attract a new type of vintner to the Valley. Though wine country had always offered a bucolic appeal, many of those who rushed the valley in the 1980s were more interested in owning a brand than making the wine themselves. The shift away from the owner-operated winery of yore to a château-type model was happy news to the escalating number UC Davis graduates who entered the job market each year. Winemaking was becoming an increasingly legitimate career path.

Though valley life seemed all blue skies in the

1980s, there was a storm brewing just over the horizon. In the planting boom

that began in 1983, vineyard land in Napa tripled, much of it planted to slake

America’s newfound thirst for Chardonnay. But Napa’s old nemesis phylloxera had

been dormant in its rich and varied soils since before the turn of the century.

The severe flooding of the winter of 1986 put more than 13,000 acres of land

under water, and the pest, which was still found in isolated pockets, was

spread valley-wide. This was of no consequence to the old vines on St. George

rootstock, but much of the Valley’s explosive growth had been planted on the

questionably resistant AxR-1. It took a handful of years for the infestation to

fully manifest, but once it did, Napa’s viticultural slate was wiped clean once

more.

In 1958 UC Davis had published a study promoting AxR-1 as a phylloxera-resistant rootstock; its increased yields and ease of cultivation effectively dethroned the ornery St. George. Though many other nations and scientific institutions denounced AxR-1 from the early days, UC Davis did not officially forswear its advocacy until 1989, at which point the damage in California was done. The resulting massive replant was considered both a blessing and a curse. Though the cost was enormous, it provided a rare opportunity for vintners to completely reengineer their vineyards, allowing for recent innovations in viticulture, as well as a shift in varietal preferences. Vineyard managers like Andy Beckstoffer and David Abreu led the charge, touting lessons lifted directly from Bordeaux, such as close-planting and vertical shoot positioning (VSP). Importantly, the replant, which extended from the late 1980s through the early 90s, was the final push toward Cabernet’s supremacy in Napa. Prior to this, Petite Sirah, Zinfandel, even Chardonnay had led the pack. Napa’s insect-driven Bordeaux makeover seemed to many to announce the Valley’s coming of age—the perfect matching of grape to region. Napa Valley was officially Cabernet country.

You Might Also Enjoy

Announcing Vinous Napa Valley Vineyard Maps, Antonio Galloni, May 2016

Vertical Tastings of Mondavi’s Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve and I Block To Kalon Vineyard Fumé Blanc, Stephen Tanzer, May 2016

Book Excerpt: A Brief History of Napa Valley, Part 1, Kelli White, April 2016

Old Vines, Deep Roots: Calistoga's Frediani Family, Kelli White, March 2016

-- Kelli White

This excerpt is taken from Kelli White’s book, Napa Valley, Then & Now. © 2015, Kelli A. White. Used With Permission.