Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Dunn Cabernet Sauvignon Howell Mountain Vertical: 1979 – 2014

BY STEPHEN TANZER | AUGUST 1, 2018

From the outset, Randy Dunn’s flagship Cabernet has been one of Napa Valley’s slowest agers and most consistently outstanding wines. This retrospective going back to the inaugural 1979 vintage showed the Howell Mountain Cabernet to be a wine of great intensity and staying power but also of restraint and class.

Remember what I said recently about the riskiness of holding Napa Valley Cabernets for more than 25 years? Well, you can waive that rule for Randy Dunn’s Howell Mountain Cabernet Sauvignon. On the contrary: Dunn’s flagship bottling presents a very different challenge. For the first 15 or 20 years of its production (the first vintage was 1979), many collectors worried that these intensely flavored, powerfully tannic wines would never come around – or that they (the collectors) wouldn’t live long enough to enjoy the wines in their full flush of maturity.

But my extraordinary vertical tasting this spring laid that fear to rest as well. Yes, the Dunn Howell Mountain Cabernets may develop at a leisurely pace but their firm spine of acids and tannins eventually begins to unclench after 12 to 20 years. And their initial dark fruit, licorice, bitter chocolate and mineral flavors are complicated and softened by mellower notes of plum, red berries, caraway seed, leather, mint and earth. And these wines are as certain to reward extended cellaring as any wine made in California. Whereas many Napa Cabs are entering their plateaus of peak maturity at age 10 or so, the better vintages of Dunn need 20 years to reach this stage. In fact, in my utterly convincing in-depth survey of 29 vintages of this wine in March, a number of 30+-year-old vintages were in fine condition, with years of useful life ahead of them.

Dunn’s Creek Vineyard (part of the old Park Muscatine)

The Origins of the Dunn Howell Mountain Cabernet

Randy Dunn, who began his career in wine as the first enologist for Caymus Vineyards and subsequently consulted at several other wineries, started his own venture by purchasing a 14-acre parcel in Angwin in 1978 (then called Trailer Vineyard but now known as Alta Tierra following a total replant in the last few years). Five of its acres had been planted in 1973 and had been mismanaged, said Dunn, so that he only used this fruit for his first three vintages (1979, 1980 and 1981), supplemented by fruit from a neighboring property and some grapes from Beatty Ranch. In 1982, Dunn introduced a separate Napa Valley bottling, which was where his lighter lots from Howell Mountain went, to enhance his fruit from numerous Valley floor sources. (On the other hand, purchased fruit from valley floor sites in Napa Valley has “virtually never” gone into the Howell Mountain bottling, according to Dunn, with the exception of the few times he blended in some “to add a fruit component” to the Howell Mountain wine.) Today, following the recent purchase of Eagle Summit vineyard with its 6.5 acres of Cabernet, the Dunn family owns about 35 acres of vines on Howell Mountain, at altitudes ranging from 1,800 to 2,200 feet, safely above the fog line. Since 1979, the Dunns have also managed the Frank Vineyard, just west of the Dunn homestead, from which they get another 6.5 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon.

The first three vintages were made at Caymus and aged at the Dunn property, and Dunn’s winery was bonded in 1981. By 1984, Howell Mountain was approved as a sub-AVA of the Napa Valley, largely through the efforts of Dunn and Bill Smith of La Jota. The Dunn Howell Mountain Cabernet made an immediate splash in the marketplace and as production slowly grew, Dunn ran out of space to store his barrels; as he has aged his wines in oak for 31 or 32 months from the outset, he needed to keep three vintages in his cellar at any one time. So in 1989 he dug a large cave into the side of the hill next to his house. The roomy tunnels (12 feet high and up to 13 feet wide) maintain a near-constant temperature of 57 degrees and provide high enough natural humidity (around 90%) to minimize evaporation. In fact, Dunn told me that during élevage his wines lose alcohol rather than water, which is all to the good.

Dunn vineyards as seen in the Vinous Map: The Vineyards of Howell Mountain, by Antonio Galloni and Alessandro Masnaghetti

A Word about Viticulture and Winemaking

As the Dunn vineyards on Howell Mountain are above the fog line, they enjoy more sunshine hours during the summer thanks in large part to clear mornings; at the same time they typically avoid the extreme afternoon heat that can affect vineyards on the valley floor. But spring also arrives later at this altitude, and frost can be an issue between bud break (which normally takes place in the last week of March) and flowering (typically during the first week of June). On the other hand, the vineyards are often able to avoid the worst effects of cool, rainy weather late in the season, thanks to better drainage and air movement.

Vine yields here are generally steady, averaging about 2.5 tons per acre, but were just 0.75 in 2008 and under a ton in 2015 due to poor weather during flowering. Dunn told me that 90% of the time he doesn’t drop crop during the summer, except in his youngest vines. In fact, he noted that his vines naturally yield a modest crop and he’d be happier if they could produce more. But the poor soils here have minimal water availability and the vines routinely produce tiny berries.

Dunn does not sort his grapes (he doesn’t even own a sorting table), choosing instead “to leave the junk in the field.” He does vigorous pumpovers three or four times per day “until things are slowing down,” then stops because with further pumpovers the cap might not come back up, which would make the pressing more complicated. Dunn told me that his tanks – at least after the earliest vintages – are too large for him to do punchdowns. He does not carry out a pre-fermentation cold soak, nor does he believe in post-fermentation maceration. Total time on the skins is typically just 10 to 12 days, which might come as a surprise to those who marvel at the tannic power of these wines: Dunn believes this characteristic is more a function of his sites’ ability to produce fruit rich in extract than it is to the way he makes his wines.

The planting of the Lake Vineyard Block 3 (circa 2003)

Dunn started by using about 50% or a bit less new oak to age his wines, then gradually increased this percentage. In 2002, in response to a few vintages when he was troubled by noticeable brettanomyces (he believes the brett entered his cellar in 1999 with some purchased fruit from valley floor vineyards), he purchased all new equipment, and sharply stepped up his use of new barrels and phased out the older ones. In short order he was aging his wines in nearly 100% new barrels. At the outset, Dunn relied primary on Vicard barrels (from Nevers oak, with a medium-plus toast). He began adding some tighter-grained barrels in 2002, and especially in 2004, and at one point was working with a dozen or more coopers, but today that number is just five or six, all with medium or medium-plus toast. He racks his Cabernets three times in the first year, then again every six months.

Since his brush with brett, Dunn has also worked with higher levels of SO2. And from very early on he has sterile-filtered his wines, a process that scarcely appears to have affected their richness or complexity. “I don’t think filtration does a bit of harm to my wine,” he noted. “It makes it lighter in color but that’s because there’s no shit in suspension to make it look dark.” Dunn has also sealed the corks of his Howell Mountain bottling in wax from the beginning, and this step may contribute to the very slow development of this wine. (Dunn said that this was done primarily to distinguish the Howell Mountain bottling on store shelves, and he makes no special claims for its possible effects on the longevity of his wines.)

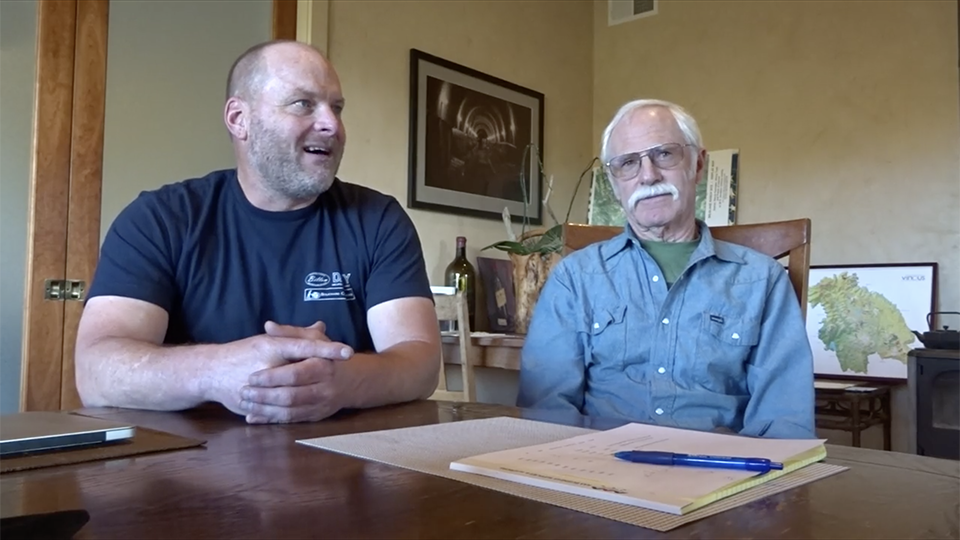

Multimedia: A Conversation with Randy and Mike Dunn

Alcohol Is Under Control

A key to the quality and style of the wines is Dunn’s aversion to high alcohol, which he believes can dull a wine and overpower its subtler flavors. “High alcohol changes a wine from being something you can enjoy through the whole bottle to one where a single glass is enough,” he explained. Until 2002, the Howell Mountain Cabernet weighed in at around 13% alcohol but even today it’s typically just under 14%, with Dunn choosing to de-alcoholize slightly in very ripe years using reverse osmosis. (He took this approach in 2004, 2009 and 2012.) Their pHs are typically around 3.8 – not particularly high for Howell Mountain Cabernet – with acidity levels around 6 grams per liter (or a hair below 4 grams expressed as sulfuric). Dunn routinely acidifies, usually during the fermentation but sometimes later, “depending on numbers and taste.” The Dunn vineyards on Howell Mountain are predominantly planted on low-pH red Aiken clay-loam soil rich in iron oxide, which gives the wines a mineral quality, but their old rootstocks are also potassium hoarders, and the potassium in the resulting wines can raise pH and buffer the wines’ impression of acidity.

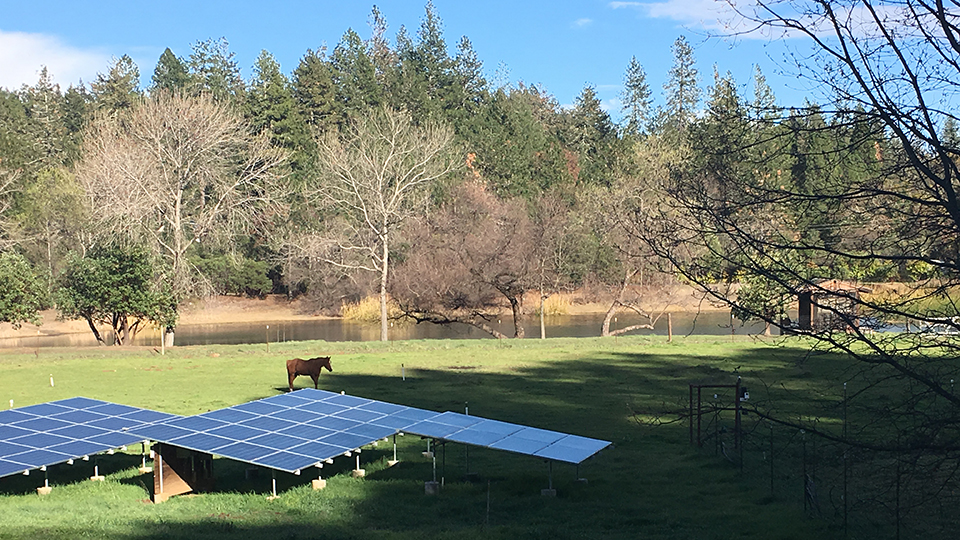

The bucolic Dunn Homestead

A Family Operation

From the start, this has been a family venture. Dunn’s wife Lori has long managed the estate, while his son Mike joined him in 1999, working part-time at the property for a few years before eventually taking over responsibility for wine production and directing the vineyard team. (Mike and his wife Kara also have their own label, Retro Cellars, specializing in Petite Sirah.) Randy Dunn’s daughter Kristina, who has a B.S. in Wine and Viticulture, was in charge of marketing and hospitality at the family estate for many years before becoming a full-time mom. And Dunn is still actively involved in every phase of the operation.

Production of the Howell Mountain bottling was 666 cases in its first vintage, 1979, but quantities have risen through the years and the Dunns now make between 4,000 and 5,000 cases of Cabernet each year, about 3,000 of them the Howell Mountain bottling. They are loath to expand further, as they’d rather work their vineyards than spend more time managing a business.

A sufficiency of Dunn Howell Mountain, with Mike Dunn

My Two-Part Tasting

When I showed up this past March at the bucolic Dunn compound on Howell Mountain, which is essentially situated in the middle of a pine forest (home, crush pad and winery, barrel caves, lake, horse pasture, and adjacent vineyards), the Dunns had prepared a good selection of vintages from five decades, dating back to their maiden 1979 release. Being a glutton for compelling wines and realizing that the odds were slim that I would ever again be able to experience an in-depth Dunn vertical with ideally cellared bottles, I decided to turn this rare opportunity into something far more comprehensive. So a couple weeks after returning home, I organized a parallel tasting of my own, filling in 14 more vintages spanning 30 years – including several of my favorites – and re-tasting a few older vintages as well. The older wines came from my personal collection, while I tasted the more recent vintages from Dunn’s cellar.

Dunn Vineyards' barrel cave

Overview of the Wines

The Dunn Howell Mountain wines don’t just age at a glacial pace; they evolve in classic Old World style, showing more soil-driven complexity, savory qualities and mellower tannins while retaining their shape and energy. (Mike Dunn noted that some vintages show a minty eucalyptus quality with bottle age – most of the Dunn vineyards are surrounded by pine trees, after all – but in my vertical tastings virtually none of the wines displayed any greenness that I would describe as intrusive.) Even as their spine of acids and tannins, which can sometimes be partly masked in the early going by extended aging in mostly new oak, begins to unstiffen, their retention of fruit even after 30+ years is remarkable – and rare. This is a wine of great intensity and staying power but also of restraint and class. Numerous times in my tasting, I found myself comparing the wines to Médocs, particularly Saint-Julien or Pauillac. Yes, Dunn Howell Mountain is a powerful, gripping wine, but it also stands out for what it isn’t: too ripe, too high in alcohol, or too much.

See All the Wines from Oldest to Youngest

You Might Also Enjoy

Multimedia: A Conversation with Randy and Mike Dunn, August 2018

Epic Dunn: Cabernet Sauvignon Howell Mountain 1979-1999, Antonio Galloni, February 2014

Vintage Retrospective: 1991 Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon, Stephen Tanzer, July 2018

Williams Selyem: Pinot Noir Allen Vineyard 1987–2016, Stephen Tanzer, June 2018

Turley Zinfandel Hayne Vineyard: 1993 – 2015, Stephen Tanzer, May 2018