Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Vertical Tasting of Beaulieu Vineyard’s Georges de Latour Private Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon: 1965–2016

BY STEPHEN TANZER | APRIL 11, 2019

Beaulieu Vineyard is one of California’s most famous and historically important wineries. The flagship Cabernet Sauvignon, the Georges de Latour Private Reserve, will be celebrating its 80th anniversary in June. The winery staged an extensive vertical at my request in March. Covering vintages reaching back more than 50 years, the tasting was directed by new chief winemaker Trevor Durling, who took over in early 2017 as only the fifth full-time maker of this legendary bottling.

The Origin and Early Decades of Beaulieu Vineyard

Bordeaux native Georges de Latour established Beaulieu in Rutherford in 1900; his wife Fernande named the small ranch in Rutherford beau lieu, or “beautiful place.” In short order Latour purchased 128 adjacent acres and planted his first vineyards—80 acres of Zinfandel and Petite Sirah—which he called BV Ranch #1. After selling grapes for a few years, de Latour began making wine in 1909, not from his own vines but from purchased fruit and grapes grown under lease arrangements. He subsequently bought the 146-acre BV Ranch #2 on the south side of Rutherford from the Catholic Church in 1910, then planted it in stages over the following several years.

Thanks to his previous experience in Bordeaux, de Latour knew that all of California’s vineyards would have to be replanted due to the spread of phylloxera, which had first emerged in Sonoma County as early as 1873. And so he began importing resistant French vines, establishing a nursery in Paris to regraft them onto Rupestris St. George and 3309 rootstock and making them available to his winemaking colleagues in California. Then, prior to Prohibition, as more and more wineries were shutting down, de Latour leased another winery and purchased tanks and barrels to increase his production capacity. He also had the foresight to obtain a permit to produce altar wine for the Catholic Church well before the 18th Amendment was passed. Thus Beaulieu was able to expand during Prohibition (de Latour even opened an office in New York expressly for the sacramental wine trade) while other producers had to close down.

The Beaulieu Vineyard winery, originally built in 1885.

De Latour then purchased the old Seneca Ewer winery in 1923. The building dates back to 1885 and its four original stone walls are still the framework of the Beaulieu winery today, situated on the east side of Highway 29 in Rutherford. (A few acres of land came with this purchase and in the early 1990s Beaulieu bought some adjacent parcels; today BV #10 comprises 91 acres.) Also in 1923, de Latour purchased the first two blocks of what would become BV #3 from a property owned by the St. Joseph’s School on the east side of Rutherford just inside the Silverado Trail, then added a third block in 1928. He purchased a final fourth block in 1933, just before the repeal of Prohibition.

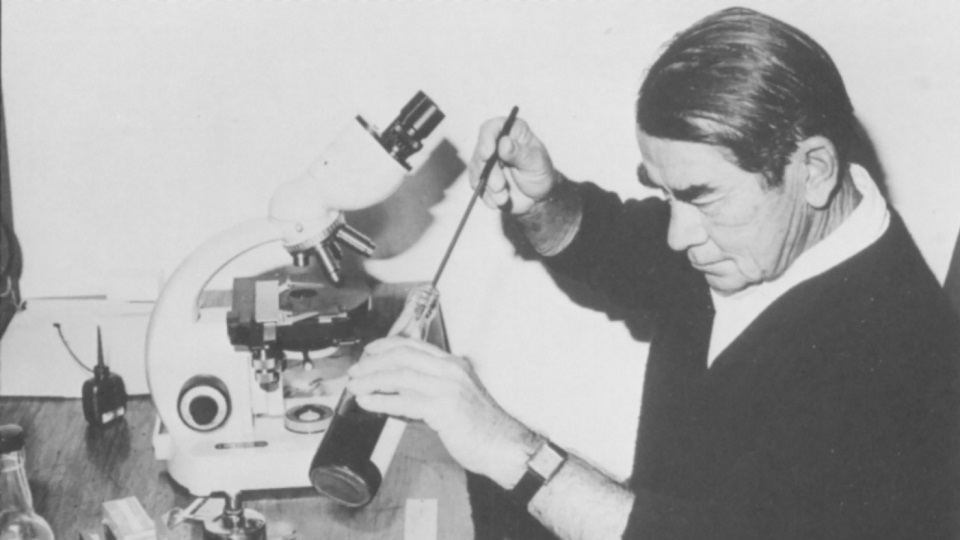

De Latour met the Russian-born viticulturalist/enologist André Tchelistcheff in France in 1938 and quickly hired him as winemaker at Beaulieu, in time to bottle the 1936 Cabernet Sauvignon, a highly concentrated wine from a growing season in which production was cut dramatically by severe late-spring frost. When Tchelistcheff arrived at Beaulieu and tasted what was at the time the de Latour family’s private wine, he insisted that it be bottled as Beaulieu’s flagship. The ’36 was released in 1940 and was labeled Georges de Latour Private Reserve after its founder, who had just died in February of that year. This bottling soon became California’s first icon wine—by most accounts, the 1936 Georges de Latour was California’s first varietal California Cabernet to gain international recognition—and Tchelistcheff became California’s most famous and influential winemaker, remaining in charge at Beaulieu through 1973.

Tchelistcheff made a number of crucial contributions to Beaulieu and to the California wine scene in general (and to the fledgling Washington wine industry as well, as Tchelistcheff began a consulting relationship with Chateau Ste. Michelle in 1967 that lasted for more than 20 years). He introduced temperature-controlled fermentation, adopted European methods of cultivating and pruning vineyards, pioneered the use of the laboratory as a multipurpose winemaking tool, and advocated for the use of malolactic fermentation for red wines. Prior to his arrival, most of the California wine industry didn’t believe that malolactic fermentation existed. Through the 1940s and ‘50s, Beaulieu’s top bottlings were frequently used as wines of state. And in 1943, George de Latour’s widow Fernande continued to expand the Beaulieu holdings. When 90 acres of the Martin Stelling Jr. property in Oakville became available in 1943, she snapped it up and it became BV #4. (Stelling had purchased a huge tract of vineyards that had been under the umbrella of To-Kalon Winery but that had been abandoned following Prohibition).

The Modern Era at BV

Here’s where the history of Beaulieu Vineyard gets complicated. Heublein Inc. purchased Beaulieu Vineyard in 1969 from the daughter of Georges and Fernande de Latour. Andy Beckstoffer, a top executive at Heublein at the time, was instrumental in the firm’s purchases of extensive vineyard land in Napa Valley and in 1970 he set up a farming company—Vinifera Development Corporation—as a subsidiary of Heublein. By 1972, Beckstoffer’s company was farming 3,000 acres, or 10% of Napa Valley. Beckstoffer then purchased his company from Heublein in 1973. In 1988 and 1993 respectively, he purchased BV #3 and BV #4 from Heublein, both of which had supplied fruit for the Georges de Latour Private Reserve in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and renamed these vineyards Beckstoffer Georges III and Beckstoffer To Kalon.

Heublein was subsequently acquired by RJR Nabisco, then sold to Grand Metropolitan in 1987, which made that conglomerate one of the largest wine and spirits companies in the world. Grand Metropolitan then became Diageo in 1997 through a merger with Guinness. In 2016 Diageo sold Beaulieu Vineyard, along with its other holdings—Provenance, Hewitt, Sterling and Acacia—to Treasury Wine Estates. Still with me?

The BV #1 vineyard, across Highway 29 from the winery in Rutherford.

After Tchelistcheff departed in 1973, the winery went through a transitional period, with general manager Tom Selfridge making several vintages with the help of Tchelistcheff’s son Dimitri. Selfridge then hired Joel Aiken in 1982 and Aiken took over winemaking duties with the 1985 vintage. André Tchelistcheff, in his early ‘90s at the time, returned as a consultant from 1991 until his death in early 1994. Jeffrey Stambor joined Beaulieu in 1989 as viticulturalist and enologist, then assumed winemaking responsibilities in 1999, with Aiken remaining as vice president of winemaking from 1999 through 2009. (During his time at Beaulieu, Aiken was the co-founder and, through much of the ‘90s, president of the Rutherford Dust Society as well as head of the Napa Valley Vintners growers’ association.)

The old stone winery and its original barrel cellar were cleaned up and redone between 1999 and 2001, and a new state-of-the-art facility in an adjacent building that was previously a barrel cellar was opened in 2008, dedicated to the production of the Georges de Latour Private Reserve. Following the retirement of Stambor at the end of 2016, Trevor Durling, who was then making wine at neighboring Provenance Vineyards and Hewitt Vineyard and for several years had worked with both Stambor and Aiken in making the Georges de Latour blend (Hewitt had supplied BV with grapes since the 1960s and continues to do so today), took over as general manager and chief winemaker in March of 2017.

Total annual production at BV has grown over the years to about 130,000 cases, excluding the BV Coastal range, which going forward will no longer have BV on the label. A Cabernet Sauvignon specialist since day one, Beaulieu’s output is still around 90% Cabernet Sauvignon and red Bordeaux blends. This production includes a sizable quantity of BV’s Tapestry Red Table Wine, a Bordeaux blend intended for earlier drinking, as well as what Trevor Durling describes as its “winemaker’s playground wines”—limited releases of Cabernets from single clones or selected lots—plus some larger bottlings from broader appellations. Production of the Georges de Latour flagship bottling reached a peak of nearly 30,000 cases in 1974 (production was higher in the ‘70s and ‘80s due to the greater use of contracted fruit during that period) but in recent years has been in the range of 6,000 to 9,000 cases.

The BV #2 vineyard in 1939.

The Georges de Latour Private Reserve, an Archetype of Rutherford Dust

Beaulieu’s flagship wine has long been based on its original two parcels, BV #1 and especially BV #2, planted on well-drained alluvial fans at the base of the Mayacamas Range on the west side of Highway 29. These vineyards, featuring gravel, sand and loam soils, are located at the widest point in Napa Valley. They enjoy more hours of sunshine than anywhere else in the Valley, but cool nighttime temperatures allow for steady, even ripening. (With around 3,000 total degree days during the growing season, Rutherford is normally a warm Region II viticultural area or a Region III.) Rutherford, incidentally, was granted appellation status in 1993, at the same time as neighboring Oakville.

Fruit from prime Rutherford vineyards typically offers excellent natural balance, with surprising natural acidity. The term “Rutherford dust,” originally coined by André Tchelistcheff as another way of saying “clean dirt,” is widely used as a general descriptor to characterize the region’s unique terroir, encompassing the notes of pencil shavings, cocoa powder, chocolate, tobacco, coffee, and loam that are frequently shown by the wines from this area, as well as their underlying minerality and powdery, fine-grained tannins.

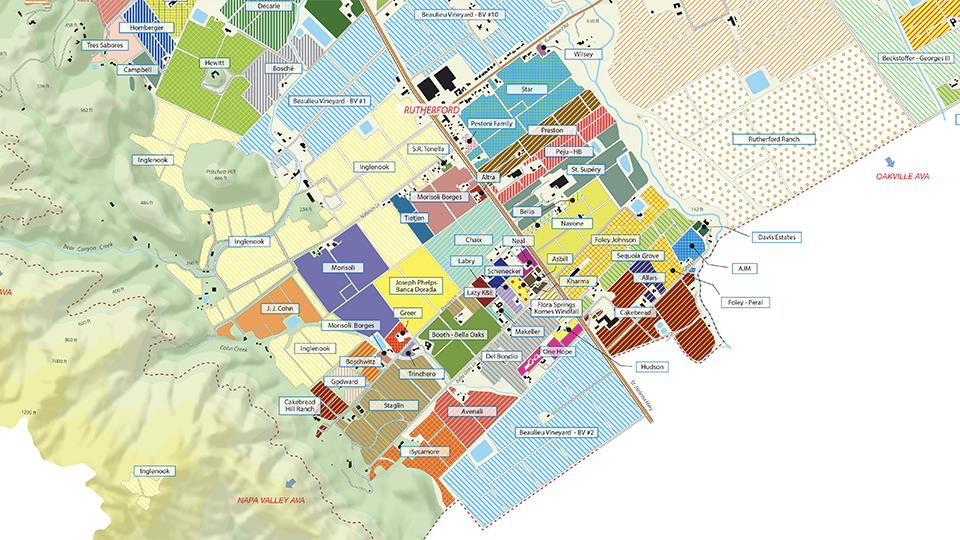

Beaulieu Vineyard’s BV #1 and BV #2, as shown in the Vinous Map: The Vineyards of Rutherford, by Antonio Galloni and Alessandro Masnaghetti, 2016.

In more recent years, some additional fruit from vineyards outside Rutherford has made it into the Private Reserve blend, including some from a hotter site in Calistoga. But from the start this flagship bottling has been a celebration of Cabernet Sauvignon. The vintages through the 1980s were 100% Cabernet Sauvignon, but a bit of Merlot from BV #1 made it into the blend in a few vintages beginning with 1990. Nowadays the only other varieties used in the blend are a tiny percentage of Petit Verdot from a block in BV #1 planted in the early ‘90s, and, beginning with the 2007 vintage, occasionally a bit of Malbec. The PV essentially succeeded the Merlot in the mid-2000s, as these vines began performing at a high level as they gained in age. But starting again in 2014, the replanted Merlot has begun finding its way back into the blend, and winemaker Durling says these vines tend to perform better in drought years like 2015. Still, the Georges de Latour has never been less than 93% Cabernet Sauvignon and indeed, until alcohol levels began to trend higher in the 2000s, the wine was always made in a relatively restrained Médoc style.

Vineyards #1 and #2 were replanted to Clones 4 and 6 in the early 1990s, and today the oldest vines that go into the Georges de Latour date back only to 1991. In recent years, the Private Reserve has been made from grapes picked over a period of about five weeks, typically from mid-September to late October, with fruit from Hewitt Vineyard usually the first to come in.

The

Evolution of Winemaking at Beaulieu Vineyard

Tchelistcheff made the Georges de Latour Private Reserve in open-top stainless steel fermenters and huge closed redwood tanks. In the early decades the malolactic fermentation took place in the redwood tanks, but by the 1980s these receptacles had been relegated to use as storage vessels. Tchelistcheff then aged the Private Reserve in mostly 180-gallon American oak puncheons, plus some smaller American oak barriques, for at least two years. He preferred to use second-fill barrels and avoided the use of new oak. A percentage of French oak was introduced in the late ‘80s and grew steadily; as of 2008, the Georges de Latour has been raised entirely in French barrels. Similarly, some new oak was introduced in the early ‘90s and the percentage of new barrels in recent years has been between 90% and 100%.

What with higher crop levels, lower grape sugars and the absence of new oak, the wines through the 1970s and ‘80s were typically austere, if not lean, in their youth, despite the fact that the winery typically held back the release of its flagship Cabernet until 18 months after the bottling. But winemaker Durling, who is quick to note that today’s consumers are demanding earlier accessibility, is continuing—and building on—the steps taken by Jeffrey Stambor to make the wines more approachable in their youth, while maintaining sound acidity levels and structure for aging.

In his selection of harvest dates Durling focuses on tannins—specifically, on not picking as long as the tannins are still green. He looks for more hang time so that he can get better phenolic ripeness before grape sugars climb too high. “We keep more natural shade than most of our neighbors do, by leaving more leaves in the fruit zone,” he told me. “It can take longer to get rid of pyrazines but that’s not normally a problem in our Rutherford vineyards on alluvial soils.” Yields are typically between three and three and a half tons per acre for Beaulieu’s best Rutherford vineyards, lower than a generation ago but moderate by current Napa Valley standards. (Smaller yields would bring higher grape sugars earlier, and would risk throwing off the balance of the wines, noted Durling.) He also makes careful use of “targeted” irrigation, even for specific vine rows within blocks. While one objective of the vineyard work is to maintain sound levels of natural acidity in the grapes, light acidification is still needed in seven out of ten vintages, according to Durling, who prefers not to bottle wines with pHs above 3.7. Incidentally, Durling described BV’s 2004 through 2013 vintages as in “a very ripe, more extreme California style, relying as much on tannins and alcohol as on acidity for structure and longevity” (pHs were particularly high through much of the 2000s). Today, says Durling, the winery is shifting back to a more classic style, as is generally the case among the best producers in Napa Valley today.

André Tchelistcheff, a giant of California wine at just five feet tall, in his wine lab.

Durling begins by chilling the must to about 50 degrees F. and adding a small dose of sulfur for a pre-fermentation cold soak that lasts five to seven days. During this period he circulates the juice for a few minutes each day to extract color and tannins “but no aggressive tannins.” He then heats the must to about 75 degrees and inoculates with what he calls “targeted yeast strains.” The fermentation temperature then rises naturally to no higher than 87 degrees. After the juice begins to cool down toward the end of fermentation, Durling maintains the temperature at 75 to 80 degrees through a period of post-fermentation maceration that is carried out in years with high-quality tannins, which nowadays means most vintages. Total cuvaison now lasts three to four weeks on average. It was considerably shorter as recently as 20 years ago, noted Durling, when the fermentation started more quickly and more extraction was done during fermentation, including more pumpovers within a shorter period of time.

Jeffrey Stambor began experimenting with barrel fermentation in 2005. When renowned enologist Michel Rolland began a decade-long consulting gig at BV in late 2006 he liked the results, and by 2008 the winery was barrel-fermenting between 50% and 60% of the Georges de Latour. Durling told me he’s now dialing back that percentage a bit, and in addition to continuing to use some stainless steel fermenters he’s also using some concrete tanks “for their softening effect on mountain tannins” (although these tanks are sealed, they are more porous, enabling some oxygen intake). Still, Durling believes that barrel fermentation on the skins is a key tool for increasing early drinkability of the wine while extracting substantial tannins. He describes Sylvain, Nadalié and Taransaud as his most important barrel suppliers (he opts for medium and medium-plus toast), noting that the first two are most frequently used for barrel fermentation. Nowadays the malolactic fermentation of the Georges de Latour takes place entirely in barriques.

A Marvelous Vertical Tasting

The vertical in March, which began with the 1965 and included most of the vintages made here in the 21st century, was nothing less than spectacular, with numerous 40+-year-old wines still in splendid form. The great ’68 was still a knockout a half century after the harvest. I should point out that at least a few of the bottles poured at my tasting came from a secret room in the winery where André Tchelistcheff stashed special bottles under ideal conditions. The room was only discovered in 2012 and even today these bottles are kept hidden from all but winemaker Durling and his team.

As is the case with most other long-running Cabernets produced in California, the Georges de Latour bottling has changed dramatically in style since the mid-‘90s, and especially in the new century. The wine had never hit 14% alcohol until 2002—later than most of the North Coast’s more recently established icon wine producers. But in fairly short order, the 2006 hit 15%, and bottled vintages since then have ranged from 14.9% to as high as 15.7% (in 2010). Consistent with Durling’s desire to make a more classic style, the ’17 and ’18 should be bottled at around 14.7% and 14.5%, respectively. Today’s wines are denser, broader and fleshier than ever before, certainly less forbidding in their youth and presenting more pristine fruit in the early going. And yet, with a couple exceptions, their Rutherford dust character comes through unmistakably—a testament to the strength of terroir shown by BV’s top vineyards.

Older, lower-octane vintages, not surprisingly, were more claret-like and less fruity—typically firm-edged, savory and classically dry in a northern Médoc way. But as a rule I did not find the element of rusticity I expected. Still, since the old wood tanks and other wood surfaces were removed from the cellar around the turn of the new century to address a nagging TCA issue, and especially since the new Georges de Latour facility was inaugurated in 2008, the wines have been more “modern.” It remains to be seen if today’s wines will be capable of evolving in bottle for a half century or more but the quality and amount of tannins, the healthy acidity and pH levels, the density of the wines and their overall cleanliness leave me confident.

See the Wines from Oldest to Youngest

You Might Also Enjoy

Dunn Cabernet Sauvignon Howell Mountain Vertical: 1979 – 2014, Stephen Tanzer, August 2018

Vintage Retrospective: 1991 Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon, Stephen Tanzer, July 2018

Williams Selyem: Pinot Noir Allen Vineyard 1987–2016, Stephen Tanzer, June 2018

Turley Zinfandel Hayne Vineyard: 1993 – 2015, Stephen Tanzer, May 2018