Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

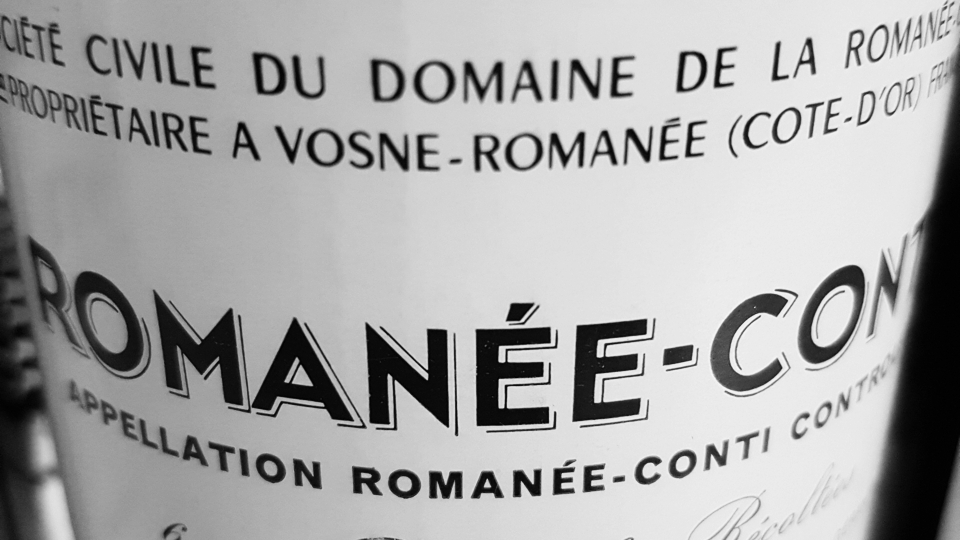

Fermented Grape Juice: Romanée-Conti 1953-2005

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 23, 2019

“More than one good judge agreed with me that it was almost impossible to conceive anything more perfect in its kind.” – George Saintsbury, writing about the 1858 Romanée-Conti in Notes on a Cellar-Book (1920)

You clicked open this article in disbelief. Like its author, you assumed that such a tasting could no longer be countenanced, that it was a Burgundy-lover’s chimera. Alternatively, you might be fulminating about words invested in a wine that cannot conceivably be imbibed by any sane person. Maybe you take umbrage that there is no cavalcade of perfect scores, notwithstanding the impudence of the title. Fermented grape juice? How dare he?! Perhaps one or two are grumbling that there is no update on the 1945 and demanding that I buy a damn bottle. And for that matter, why no 1947 Romanée-Conti? That pristine case of double magnums just arrived from China and requires a drinking window.

This article exists for a very simple reason: I tasted the wines. I could have vegged out in front of the TV on that drizzly Wednesday night. But I decided that my evening would be better spent at The Connaught, where one Omar Khan had organized a once-in-a-lifetime dinner, two of the attendees successful bidders at the Musique et Vin auction the previous June.

As a wine writer, my duty is to share thoughts and findings, even if they verge on polemic. No wine should be exempt from critique. Strip the label off a bottle of Romanée-Conti and a bottle of Bourgogne Rouge and you have the same thing: two bottles of Pinot Noir with their own strengths and weaknesses. I was two decades into my career before this tasting beckoned, and I doubt it will ever happen again (not that a repeat would completely ruin my day). Indeed, it was 17 years before even a single Romanée-Conti blessed with bottle age passed my lips. Up until that point, my assessments of a wine renowned for its longevity were limited to showings in barrel and just after bottling. (Yes, I know; poor me.) Like many people, I dreamed of tasting a mature Romanée-Conti, not only for the pleasure, but also to deepen my understanding and to cast my own judgment. Here was a chance to do just that – and go further by comparing multiple vintages against each other.

In writing this piece, I wanted to avoid hagiography. I encourage you to read the history of the vineyard, because it is full of colorful tales that are hopefully enjoyable to read. As with any winery, I endeavored to approach the subject matter with respect and without placing it upon a pedestal. I wanted to find out in fundamental terms: What is Romanée-Conti but fermented grape juice?

History

No maiden trip to the Côte d'Or is complete without paying homage to Romanée-Conti and taking the obligatory selfie, leaning against the lichen-mottled cross at the foot of the vineyard with its plaque dedicated to Gaudin de Villaine. Even after 20 years, if time permits, I make a quick detour just to drive by and… absorb. The vista across the vineyard is as transfixing now as it was that first time. But what are the domaine’s origins, and how did it come by such status? Several books tell the story; my favorite is Richard Olney's monogram, which is long out of print but well worth tracking down.

The domaine’s history stretches back eleven centuries to the priory of Saint-Vivant de Vergy. Olney pinpoints a land transaction in 1276 whereby prior Yves de Chasans acquired three journaux in Clos de Saint-Vivant that would have contained the vineyard then known as La Romanée. The following centuries witnessed various ecclesiastical transactions that I will bypass in this account.

Instead, let’s fast-forward to the next crucial date, August 28, 1631, when the land passed to the de Croonembourgs through marriage. Four generations of the family owned La Romanée, during which both the quality and the stature of the wine increased, in tandem with higher prices than surrounding vineyards, some five or six times those of distinguished growths by the 1700s. Then, on July 18, 1760, Louis-François de Bourbon, known as the Prince of Conti, acquired La Romanée from André de Croonembourg for 80,000 livres, a sum that sent shockwaves through the region (not unlike François Pinault's purchase of Clos de Tart in 2017). The contract of the sale describes the property as "a vineyard called la Vigne de la Romanée, enclosed by walls to the south and to the east containing thirty-seven ouvrées and a half including the enclosing walls... [and] another little parcel of vines called Richebourg, contiguous with La Romanée.” The wine itself would have been made in Vougeot.

Louis François de Bourbon, a.k.a. the Prince of Conti

There is a fascinating backstory to the acquisition. La Romanée was coveted by Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV. Louis François de Bourbon’s mother, Louise Élisabeth de Bourbon, had introduced Madame de Pompadour to the king, yet rumor around Versailles was that Pompadour had sabotaged Louis François’s military career. Therefore, the identity of the buyer remained secret until after the contract was signed, for fear that Pompadour would thwart the sale. A ruse was hatched whereby an intendant, Jean-François Joly de Fleury, stood in as a kind of decoy buyer. It worked. Louis François de Bourbon took charge of the vineyard, appended “Conti” to the name, and announced that henceforth Romanée-Conti was for his private use, enhancing its fabled status. One interesting fact gleaned from Olney’s book is that in those days, the wine would probably have contained around 20% Pinot Blanc, as the addition of a white grape variety was said to impart finesse. It would also have undergone a very brief cuvaison, since long durations in vat signified an inferior wine.

Louis François Joseph de Bourbon succeeded his father as Prince of Conti. During the Revolution, he fled in disguise for Turin, returning to Burgundy in 1793, at which time he was arrested and imprisoned. From his cell, he learned that La Romanée had been put up for sale as a bien nationale, although it took some months to find a buyer. Throughout the following year, posters extolling the wine as "the most excellent of all those of the Côte d'Or" appeared around Burgundy, and at this time we find the first mention of the wine Romanée-Conti. The vineyard was sold to the Defer family, whose tenure was relatively brief; they auctioned it off on September 22, 1819. The winning bidder was Julien-Jules Ouvrard, who paid Fr 60,050. As well as owning large slices of propitious vineyard, Ouvrard was a powerful figure and mayor of Vosne throughout much of the mid-1800s; however, his ownership was contemporaneous with a slump in Burgundy wine prices. In 1869, Romanée-Conti was on the market once more, and Jacques-Marie Duvault-Blochet finally purchased the domaine for the sum of Fr 260,000. Duvault-Blochet was a man of impressive business acumen who bought practically the entire 1846 vintage across the Côte d'Or and sold it at a handsome profit. He transferred the winemaking of Romanée-Conti from Vougeot to Château du Passetemps in Santenay, and when he died in 1874, there ensued a complex series of inheritance transactions within the Chambon family. Romanée-Conti eventually ended up in the hands of siblings Jacques Chambon and Marie-Dominique Madeleine Gaudin de Villaine.

The vineyard was in a sorry state when Marie-Dominique’s husband Edmond Gaudin de Villaine took over the management in 1911. Over the next three decades, he reconstituted Romanée-Conti as well as registering the name "Domaine de la Romanée-Conti." He resisted replanting the vines with American rootstock to protect them from phylloxera, like many owners of the noblest vineyards; instead, he injected the ground with carbon disulfide, an insecticide that did not cure phylloxera but warded it off. Most importantly for the region, together with the Marquis d'Angerville and Henri Gouges, he advocated rules and regulations to guarantee authenticity for Burgundy wines, whose reputation was being sullied by the more unscrupulous négociants. His most important decision about the domaine itself was appointing an ex-army officer, Louis Clin, as régisseur. Clin played a key role in overseeing many of the treasures from the first half of the 1900s.

Alas, by the 1930s the market for wine was in malaise. In his book Pearl of the Côte, Allen Meadows relates how the domaine had to be subsidized by the family’s farm in Moulins-sur-Alliers. Co-shareholder Jacques Chambon decided to relinquish his share, selling it to an Auxey-Duresses-based négociant, a young man by the name of Henri Leroy. Leroy made the difficult but ineluctable decision to uproot the vines in Romanée-Conti after the 1945 harvest, when just 608 bottles were made, such was the untenable unproductivity of the vineyard after spring frost and lack of carbon disulfide. Olney asserts that the vines would have dated back to 1585, when Claude Cousin purchased the vineyard from the priory of Saint-Vivant with a perpetual lease stipulating that vines had to be replanted with good-quality replacements, achieved through provignage. It seems inconceivable that the vines were five centuries old, until you read that when they were wrenched from the earth, their root system formed a tangled mass several meters in diameter, so dense that you could not see sunlight through it. (If only someone had taken a photograph; that is something I would have loved to see.) The vines were replanted in 1947, delayed one year because of an error in the preparation of grafts, and consequently Romanée-Conti would not reappear until the 1952 vintage. Two years later, Leroy divided his half-interest between his daughters Pauline and Marcelle, or as we know her better, Lalou Bize-Leroy.

Clin had hired André Noblet in July 1940 to assist him in the cellars, and Noblet vinified his first wine as chef de culture and chef de cave in 1946. To quote Olney: "Noblet thought of his wines as his children." That is worth remembering, since this article includes wines nurtured under his aegis. Edmond Gaudin de Villaine’s son Henri succeeded him, and he worked closely with Henri Leroy until 1974. In that year, de Villaine handed management over to his son Aubert, born in 1939. Henri Leroy died in 1980 and André Noblet retired four years later, succeeded by his own son, Bernard. I tasted in the cellar a few times with Noblet, a lanky, hulking gentleman who, allegedly like his father, seemed to enjoy visitors of the fairer sex and was prone to analogies not exactly in line with the “Me Too” generation. My favorite memory of Noblet is when Aubert de Villaine instructed him to serve a bottle of La Tâche blind for a couple of American importers and myself. Noblet returned and handed us the glasses. De Villaine took a quick sniff and asked if this was La Tâche. Without a mote of contrition, Noblet answered that on the spur of the moment he had decided to pour us Romanée-Conti instead. Aubert being Aubert, he kept his exasperation muted. Sotto voce, I said, “Merci, Monsieur Noblet.”

Aubert de Villaine and Lalou were co-gérants, directing the domaine together, though they have very different personalities and clashed over distribution and conflicts of interest with Lalou’s namesake domaine. The partnership ended with Lalou’s acrimonious ouster from the board in 1992. Charles Leroy, the eldest son of Pauline, replaced Lalou, but he was killed in a car accident just a few months later. His shares went to Henri-Frédéric Roch, who passed away in 2018, and they now belong to Lalou’s daughter, Perrine Fenal.

Winemaker Aubert de Villaine of Domaine Romanée-Conti

Aubert de Villaine has been the constant throughout the last four decades. Erudite and philosophical, down-to-earth (figuratively and literally), soft- spoken and sacerdotal, yet unafraid to make tough decisions, he has overseen the most significant change in perception of Romanée-Conti from a respected wine to an icon without equal. It’s impossible to believe now, but only a small niche group of oenophiles were really interested in buying Romanée-Conti in the 1970s. I remember one merchant recalling how he spent a fruitless day driving around London trying to offload two cases of the 1978. I even have it on good authority that in the 1970s, for a brief period, you could buy bottles of Romanée-Conti from the Tesco supermarket shelf in my hometown of Southend-on-Sea. (If only I’d had a penchant for Pinot Noir when I was five years old.) It’s challenging to reconcile these images with the wine’s present hallowed status.

A new chapter is currently opening as Aubert’s nephew Bertrand de Villaine takes over the running of the domaine. Aubert’s shoes are impossible to fill, and I feel that Bertrand wisely intends to be his own man. I’ve seen him grow into the role and I’m certain he will chart the coming years with success.

The Vineyard

Romanée-Conti is in fact entitled La Romanée-Conti, although the definite article is rarely used. The 1.814-hectare rectangular vineyard lies about a minute's walk from the fringe of the village, just above the southern flank of Romanée-Saint-Vivant and directly below La Romanée. On the opposite side of the ascending single lane lies a third monopole of La Grande Rue, and to the north is Richebourg. The vineyard rises from 260 meters to 285 meters above sea level, with a slight tilt to the south that both increases exposure to the sun and helps protect the vines against frost. The bedrock is a hard calcareous limestone, or entroques, that is rich in marine fossils. Above this lies an 8- to 10-meter-deep stratum of marl composed of innumerable tiny fossilized oyster shells toward the bottom of the slope, and more oolitic limestone toward the top. The topsoil comprises about one-quarter pebbles and gravel, and around 35–40% clay with a high iron oxide content that lends the surface its reddish tinge. There is no unique topographical, geological or pedological feature that distinguishes Romanée-Conti from other grand crus. Without any idea of where you are, you might be astonished how unremarkable it looks. The secret? Well, despite numerous scientific studies, we don’t know and (thankfully) never will.

The vineyard at Domaine Romanée-Conti

As already mentioned, the entire vineyard was replanted in 1947, which gives you an idea of the average vine age. A small, 0.17-hectare parcel was replanted in 1994 at a higher density, 15,000 vines per hectare, although de Villaine was unconvinced by the results, and so in 2008 another 0.19-hectare parcel was replanted at 11,000 vines per hectare, the same as the rest of the domaine. From 1947 until the 1980s, the vineyard, like the rest of the domaine, was populated by vines through sélection massale and using 161-49 rootstock, known for its restrained vigor and tolerance for calcium. Pruning is guyot with some of the more vigorous plots pruned cordon Royat. In recent years, de Villaine has eschewed deleafing the vines, as he felt it produced unnecessarily dark and heavy wines, and of course, maintaining the canopy in a season like 2003 provided crucial shade to the grapes. The domaine turned to organic viticulture in 1985, and for many years, de Villaine tentatively embraced the philosophy of biodynamics. The vineyard was converted in 2007 and is currently managed by chef de culture Nicolas Jacob, who joined in 2006. Apart from the human workers under his charge, the team includes a horse used to plow the vineyard and eliminate soil compaction by use of tractors. Romanée-Conti is presently their only vineyard entirely plowed by equine power.

The winemaking is straightforward, as it tends to be for most great wines. You have the best terroir in the world – why would you want to interfere? To quote de Villaine himself, “Nothing is more difficult than to act simply; the ideal is to do nothing.”

Examining picking dates, I find that Romanée-Conti is harvested neither early nor late. The domaine has a reputation as a late picker; however, de Villaine will always avoid the risk of sur-maturité to maintain freshness in his wine. The same team of around 90 pickers will harvest all the domaine’s vineyards. A selection is made in the vineyard and then again on a table de trie as the grapes enter the cuverie. Stems are included in the vinification, but unlike Domaine Leroy, the amount is judged by examining their lignification. It tends to be 100% only in solar vintages like 2005 and 2009, and more often it is between 70% and 90%. Grapes are cooled to around 15°C at the start of the alcoholic fermentation in large traditional wooden vats, and the temperature rises to around 35°C. Only natural yeasts are used, and they are encouraged by remontage at the beginning and later by twice-daily pigeage. After the cuvaison of around 18 to 21 days, the vats are run off and the vin de presse is extracted using a Bucher press, though the final volume in the blend is usually 5–10%. The heavy lees are removed and the wine is transferred into 100% new oak, though this has only been practiced since 1975 and therefore does not apply to the older vintages in this article. Oak is sourced from the Tronçais and Bertranges forests, and barrels are made at the François Frères cooperage, augmented by a few casks from Taransaud. There is no fining or filtration when the wine is bottled after the second winter, usually around March and in accordance with the lunar cycle. Around 400 cases are produced each year, though readers should note that I have provided exact quantities, along with picking dates and yields, in the tasting notes.

The plaque of Domaine Romanée-Conti

The Wines

The dinner was not exclusively Romanée-Conti, but when additional bottles are of the caliber of 1978 La Tâche and 1971 Richebourg, who’s going to complain? Thirteen vintages of Romanée-Conti spanning five decades were served, the youngest a 2005. Alas, the two oldest bottles were out of condition, and so they are replaced here with three additional tasting notes, for 1953, 1961 and 1965. The wines were served over dinner at The Connaught, the menu designed by celebrated chef Hélène Darroze. This leisurely pace meant that we could monitor and compare bottles over a four-hour period. In the case of one vintage, this proved to be critical.

We began with two vintages of Montrachet. The 2004 Montrachet comes from a tricky vintage, but this showed extremely well, displaying wonderful complexity on the nose, superb balance and a cheeky touch of nutmeg on the assertive, compelling finish. This will not improve with further bottle age, though it is endowed with the vigor to suggest it will continue on its plateau for another 15 to 20 years. I could not get my head around the 1993 Montrachet, which had a pungent marshy aroma that gained an aszú-like character with aeration. Very nutty and phenolic on the nose, it is a wine that I found “interesting” more than “pleasurable,” perhaps lacking the typicity one seeks in this grand cru.

There were two standout vintages from La Tâche. I have been fortunate to drink the 1966 La Tâche three times recently. It is a vintage where the domaine truly excelled, and it possesses such freshness and grandeur that it can leave you spellbound. This bottle was a stunning example, though an even better bottle appeared a few months later and will appear in a forthcoming article. The 1978 La Tâche was served alongside the 1978 Romanée-Conti so that we could compare the two. On both occasions that I have made a direct comparison, La Tâche has convincingly shown better, conveying more harmony and depth and greater length than Romanée-Conti. The 1959 and 1969 La Tâche were not faulty, though I have encountered better examples in the past. I tasted the former at another dinner in Burgundy around the same time and so I include that tasting note, although I’m still waiting to encounter the elusive bottle that fulfills expectations.

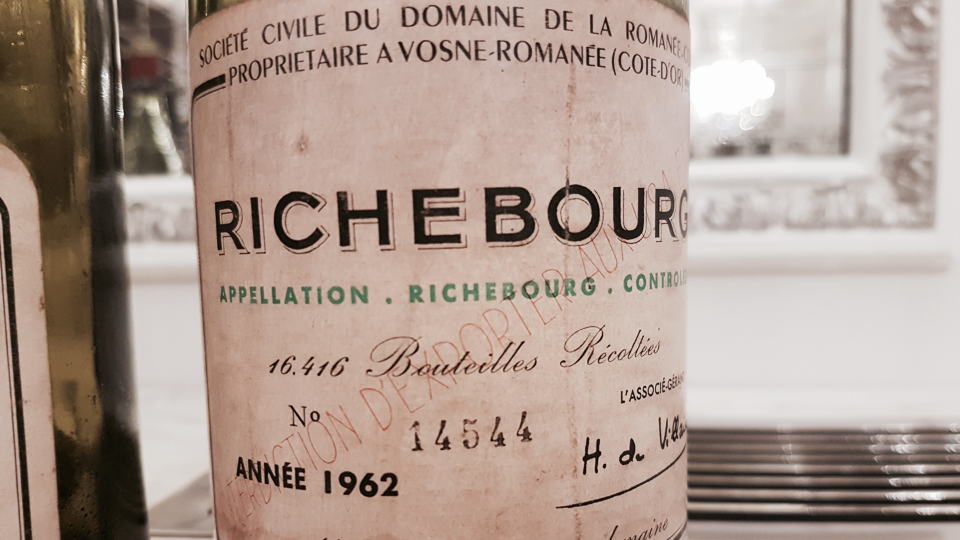

One of my favorite wines of the entire evening was the sublime 1962 Richebourg. Not that I drink 1962s every day, but it was a year when the domaine didn’t put a foot wrong, and the handful of bottles I’ve tasted have been magical. The 1962 Richebourg offers entrancing, fragrant Earl Grey–like scents, and heavenly delineation and persistence on the palate – a magnificent and regal Grand Cru. It edged out a beautiful 1971 Richebourg that shared the Earl Grey tincture on the nose but displayed a little more richness and girth. Beguilingly harmonious and elegant, it challenges the supremacy of the 1971 Romanée-Conti served alongside, though unlike the 1978 La Tâche, it could not surpass it.

Now, the main event. Though skeptics will argue that it’s not humanly possible, I approached the wines with a blank sheet, prepared to praise and criticize as I saw fit, as I would with any other wine. The proof is in my notes and scores. I was actually quite surprised by – and indeed welcomed – the sober discussion that accompanied every flight, each bottle highlighting both the virtues and the shortcomings of another. This should come as no surprise, since the domaine has always sought to translate the vagaries of the growing season, and that should be reflected in the wine. Instead of broaching the wines chronologically or in tasting order, I have grouped them together according to how they met expectations vis-à-vis vintage reputation.

Two bottles were garlanded with the loaded word “perfection.” Two vintages soared above others. Two vintages risked exhausting my cache of superlatives. One that I have fêted previously on Vinous is the astonishing 1999 Romanée-Conti, which effortlessly tempers the power of that growing season with otherworldly precision and harmony to create a profound expression of Pinot Noir. Interestingly, it is one of the highest yields ever, at 32hl/ha, equating to 6,917 bottles, or almost double that of the 1993. Yet that clearly did not prevent de Villaine and his team from creating a masterpiece. The other standout is equally predictable. The 2005 Romanée-Conti was, unusually, picked over two days instead of one. This peerless elixir delivers crystalline beauty, a hint of loam on the nose and haunting precision on the palate. Like the 1999, it takes a growing season that begat intense and demonstrative wines and puts it on a leash so that it obeys the terroir. Contemplating this 2005 over an hour, I could not find any imperfection. Together with the 1999, it represents the apotheosis of Pinot Noir.

But what about instances where the esteemed vintage sets up expectations of perfection? Enter the 1990 Romanée-Conti. I have never warmed to this vintage apropos of DRC, because unlike the 1999 and 2005, the growing season dictates the wine. Don’t get me wrong; it’s a phenomenal tour de force, figgy on the nose, lush and sumptuous on the palate. A little too exotic, perhaps, and the lushness comes at the expense of precision. I know others will vehemently disagree, and maybe, if I ever get a chance to drink it again, I might alter my opinion. The other presumed gem is the 2002 Romanée-Conti. This is a vintage that I adore, and surely it was destined for perfection. However, I was not the only person to notice that the stem addition was not quite as well integrated as the 2005. Everything else was perfect, and yet my conclusion is that a few more stems detached from the berries might have engendered a better wine.

A vintage that has blossomed in recent years is 1993. The bottle of 1993 Romanée-Conti was initially believed to be corked (proof that TCA cares little how hallowed a bottle might be) – or was it? Instinctively I felt that it was just a little funky. I returned to my glass after two hours, and – hey presto! – the funk had dissipated to reveal an attractive wine, if not quite as riveting as anticipated. It is interesting to note the yield of 14.87hl/ha or just 300 cases, due to the most intense mildew pressure for years. As I have already argued, the domaine conjured better La Tâche than Romanée-Conti in 1978. Although it is a delicious wine that has aged well, the Romanée-Conti does not quite shake off that period’s rusticity. While the 1978 La Tâche clearly has the stamina to mature for many years, perchance the 1978 Romanée-Conti’s peak is behind it. Then there is the 1953 Romanée-Conti, which was actually opened as a backup at another tasting. This was only the second vintage since replanting, so the vines would have been just six years old. That did not necessarily preclude making an amazing wine, but maybe the young vines needed a few more years’ experience, or, at 65 years old, the wine might simply be past its best.

Some vintages were simply fantastic, delivering exactly what I would expect, even if they could not match the perfection of the 1999 and 2005. I tasted the 1996 Romanée-Conti at the dawn of my professional career and reeled out the superlatives back then. Almost two decades later, it has an almost saturnine, oyster shell and brine bouquet with hints of truffle. Typical of the vintage, this has quite a rigid backbone and the most pronounced marine influence of all the bottles tasted. Maybe it lacks a touch of tension and precision on the finish, but otherwise it showed extremely well. The 1991 Romanée-Conti was picked late, on October 4. This might be contrary to received wisdom but I prefer it to the 1990. The 1991 was the first vintage where Aubert de Villaine had total control of the domaine, and it shows in the whole range of wines, not just the Romanée-Conti. It is wonderfully defined on the nose and shows a greater level of transparency and precision than the preceding vintage. The 1961 Romanée-Conti is another bonus note. I had encountered the ‘61 once before in Beaune, courtesy of a bottle from the domaine’s cellars. This was served blind over lunch last December and performed similarly. A late-picked vintage (October 7), it has a gorgeous red berry and blood orange bouquet with touches of chestnut. The palate feels quite thick and maybe brawny compared to more recent vintages, yet it has ethereal balance thanks to the acidity and outstanding length.

How about difficult growing seasons where Romanée-Conti transcends the limitations? The 2000 Romanée-Conti is a little sinewy and short compared to others but displays exquisite balance and poise. It is well into its secondary phase, and I suspect you would want to drink it over the next decade. Perhaps we can also include here the 1980 Romanée-Conti. This is an odd vintage, forgotten by many, although I have enjoyed many positive encounters, and it would be more respected had a greater number of Burgundy growers gotten their act together after the 1970s. Alas, only a small core (such as Henri Jayer, Jean-Marie Ponsot and Aubert de Villaine, to name three off the top of my head) had the wherewithal to exploit the growing season. The 1980 is a gorgeous wine, quite deep and rounded, rustic like the 1978 and maybe past its peak, yet the aromatics are fabulous and it exudes density and class.

Neither the 2000 nor the 1980 vintage has a reputation as wretched and disparaged as the one that the 1965 Romanée-Conti was born in. It was mischievously poured by Aubert de Villaine at a dinner held on board the Cutty Sark in Greenwich, and all 150-odd attendees were invited to guess the vintage. You could hear the gasp when it was revealed. How could a wine from a zero-star growing season taste so ruddy marvelous? It must be the picking date. Romanée-Conti was not picked until October 23, enabling the fruit to achieve ripeness when other growers had already either given up or salvaged what they could by picking early. It is not the best Pinot Noir I have ever tasted, but it is certainly one that mocks its vintage reputation and defies all expectations.

Finally, we come to the Romanée-Conti that coincides with my birth year, which also happens to be a great Burgundy vintage. So in a sense, this was a desert island bottle, and fortunately it lived up to expectations. Offering melted tar and pressed rose petals on the nose, and a core of sweet fruit and an almost viscous texture in the mouth, the 1971 Romanée-Conti is an exquisite wine that arguably is just entering its graceful decline.

Final Thoughts

The quality of Romanée-Conti did not come as a surprise, though realistically, I did not anticipate unwavering perfection. Had you asked my expectations beforehand, I would have predicted one or two perfect wines and several exceptional ones. That proved to be the case and reflects my reviews after bottling over the last two decades.

What did I learn? I learned that with maturity, Romanée-Conti gains weight and density not dissimilar to La Tâche. Just after bottling, Romanée-Conti is ethereal and poised. Sometimes it seems lightweight, almost gossamer, compared to the domaine’s other crus, and you wonder what all the fuss is about. But maturity gifts Romanée-Conti sinew and backbone. Analogizing to a musical score, time fills in the spaces between the notes with layers of instrumentation so that eventually you hear the entire symphony. Romanée-Conti is deceptive in terms of longevity and blessed with an extraordinarily prolonged drinking plateau, testifying that density and fruit concentration are not necessarily prerequisites for a long and happy life. Then again, that pertains to the region and grape variety as a whole; Romanée-Conti just takes it to another level. Also, Romanée-Conti is not a shoo-in for the domaine’s best wine each year, and there are some vintages, like the 1978, where La Tâche is superior. Some mavens even argue that La Tâche is the crown jewel. Although both are monopoles, La Tâche is in fact a relatively large production, and the amalgamation of terroirs arguably contributes to a more complex wine than Romanée-Conti, which is ostensibly a snapshot of a small area of uniform terroir. A blind head-to-head between the two through the years? Tell me where and when, and I’ll be there.

The provocative title of this piece is not intended to be flippant. The three startling words strip Romanée-Conti down to what it is: fermented grape juice. To understand the wine and to critique it, this is the ideal starting point, because history, reputation, fame, label, the charm and charisma of Aubert de Villaine… they don’t taste of anything. Yes, they enhance the experience, but they have no direct influence on the wine’s olfactory or gustatory properties. Paradoxically, these intangible elements fuel and exponentially magnify demand because they are incomparable and place Romanée-Conti at the snow-capped apex of the pyramid, which has been the case throughout Burgundy’s history, in good times and bad. I hope that in this article I have managed to separate objective appraisal from these extraneous factors and my appreciation of simply having a seat at the table.

The one facet of Romanée-Conti unmentioned until now is its price. Believe it or not, the subject never arose in conversation over dinner, and I did not want it to color this article. Maybe you’ve already punched figures into a calculator to work out the cost of libation and mentally listed what you could buy for that amount of money. I confess that in my wish to examine each wine with perspicuity but without intoxication, I sacrilegiously left thousands of pounds worth of Pinot Noir in my glasses. Is that being professional or being an idiot? Maybe both. Later on, as I was walking through Waterloo Station, a homeless man asked me if I could spare some change, and I rued the inequality of the world. On the other hand, the evening had raised thousands of euros for a deserving cause. I will leave the morality debate for another time.

The secondary market value of Romanée-Conti recently topped $20,000 a bottle, although as recently discussed on the forum, the domaine releases new vintages for a fraction of what zillionaires are willing to pay. I am often asked if Romanée-Conti is worth the price. My answer to the question is simple: no. In the eyes of most ordinary people, it is irrational, absurd or even obscene. Then again, if you could easily afford it, why would you deny yourself the best? I can promise you that I wouldn’t.

You have to seize opportunities when they arise, not least when they are once in a lifetime.

(My thanks to Omar Khan for inviting me to this extraordinary dinner. As I mentioned, all proceeds went to the Musique et Vin charity.)

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

This Is Not Morey-Saint-Denis, Neal Martin, March 2019

Bottles Never Forgotten - Burgundy Edition, Neal Martin, March 2019

Caught Somewhere in Time: Clos de Tart 1887-2016, Neal Martin, February 2019

The Picardy Third: 2016 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti In Bottle, Neal Martin, February 2019

2017 Burgundy: A Modern Classic, Neal Martin, January 2019