Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

The Magician’s Fool: 1950s Bordeaux

BY NEAL MARTIN | FEBRUARY 28, 2018

Magicians. Bloody magicians.

Yeah, we all watched them growing up, whether it was perma-tanned David

Copperfield pulling a mildly surprised elephant from a top hat or Paul Daniels

vanishing before an audience’s grateful eyes. I cannot deny that I enjoyed the

entertainment. However my cynical disposition meant that in the unlikely event

of participating in any magician’s act, then I would see through the facade. I’m

no fool. I’ll show them who’s the clever one.

So I am invited to Mr. A’s private dinner and the theme? The 1950s. Arriving at our host’s mansion, I am the only person not dressed as a member of the T-Birds, all greased back hair, jeans and leather, though one chap has ticked one off his bucket list and come dressed as a disturbingly convincing Marilyn. The radio plays the golden greats of rock n’ roll: Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry and Elvis, whilst Mrs. A has prepared trays of mini-hamburgers (100-points NM). Naturally, all the wines were born in this decade and some pretty serious names too. I can’t wait...

But first, for our pre-prandial entertainment, Mr. A has booked a magician. I will be honest, when he enters the room in his glittering lamé jacket, I am hoping that we can get pre-prandial prestidigitation over and done with it quickly because I want to get my tonsils round that 1959 Palmer. But anyway, we form a horseshoe and the show begins. The first couple of tricks are simple sleights of hand and I barely raise an eyebrow. I’ve seen it before. But as his act progresses the conjuring provokes ever-increasing degrees of awe and incredulity. I am hooked. How the hell did he do...wait...now bottles of DRC are materializing from empty cylinders, a trick last seen in Rudy Kurniawan’s kitchen, just before the FBI rang his doorbell. I make a mental note to contact DRC’s agents. This chap would be useful helping out with limited allocations. Need another few mags of La Tâche? Ta-da!

Each of our party is invited to take part and come the final trick he choses yours truly. This is my moment. This should be easy. I’ve had enough of this tomfoolery.

The magician hands me a pack of cards and invites me to shuffle. He turns his back and I choose a random card and return it to the pack. It is the nine of spades. He asks if I am happy with my choice and just as he is about to continue, I doth protest and ask to choose another one. I do this twice. He’s on edge. What kind of mug does this guy think I am? Eventually I settle on the three of hearts. I place it back in the pack and then the magician asks me to hold out my hand, palm upwards perfectly flat, as if I am about to walk like an Egyptian. He places the pack into my palm. Then I enclose the deck by placing my other hand over the top, whereupon he casually walks over to the opposite side of the room. My brain works overtime speculating how he could guess my chosen card. He is rabbiting on now. I’ve caught him out. He’s playing for time. Get that Palmer open...

Then he utters the words. “He no longer has the deck in his hands. They’re here on my hand. He is holding a block of glass.”

W.T.F. I swear that about half a second before the big reveal I felt the sharp edge of glass however, my brain cannot compute this irrational metamorphosis and...HOW THE HELL DID HE DO THAT WHEN HE IS ON THE OPPOSITE SIDE OF THE ROOM! I mean he placed the deck in my outstretched hand. I saw them there. I put my other hand on top. The cards cannot escape. Nothing can enter. How did card become glass? I’ve been staring at my hand the entire time. There are audible gasps around the room as logic and a majority of Newton’s laws of physics come apart at the seams, applause erupts around the room. I half-heartedly clap because a few cerebral synapses have short-wired trying to work out what just transpired.

The only way I could recover was by drinking astonishing Claret. I should point out here that whilst this was an evening of jollity, banter and rock ‘n roll, these bottles were not only serious in quality but of sound provenance, some having been acquired at auction from the ex-Nicolas cellar and other ex-château. My tasting notes were written before the fun began and the music turned up loud, notwithstanding that I could monitor their progress over the course of two or three hours afterwards.

We now look back at the 1950s as a golden age for Bordeaux, a continuation of those halcyon postwar vintages courtesy of 1953, 1955 and 1959, not to mention pretty good 1952s and a cluster of Right Bank 1950 gems. It would not be until the 1980s that the region enjoyed such a benevolent run of vintages. It is easy to forget two things. Firstly, most Bordeaux château including the First Growths barely scraped a profit indeed a majority even at the top end made a loss. The merchants, still bottling much of the production, dictated the market and called the shots. Secondly, that market was restricted to a very small niche of oenophiles. In these austere ration book times, wine was a luxury reserved for the tiny number of the upper class and noble professions such as doctors, lawyers and the clergies.. Vintages now revered as 20th century pinnacles were not met with the hoopla commonplace nowadays, but with a few bon mots in periodicals such as Cyril Ray’s “Wine & Food” magazine and merchants’ brochures. It was the 1959 vintage that finally restored some essence of profitability for the first time after the Second World War.

We began with a rare dry white Bordeaux wine, the 1950 Laville Haut-Brion. To be honest, I was not taken with this wine that lacked the sparkle and vivacity of some of the great Laville’s from the 1960s such as the 1962 and 1964. Others appreciated more than myself, but for me it lacked clarity and just felt rather decrepit, unsurprising given age and mediocrity of the growing season.

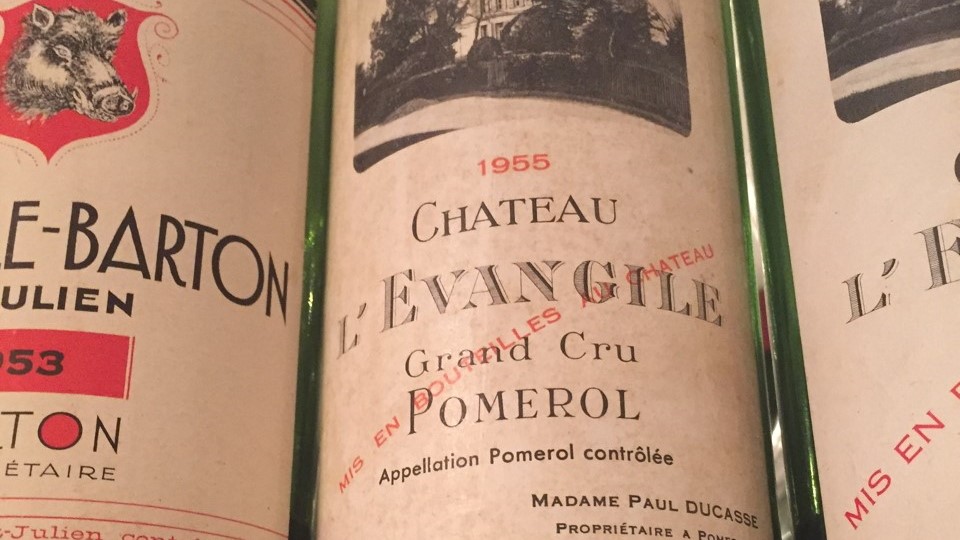

Bottles of L’Evangile from this era are now very difficult to find. According to the label, this 1955 was shipped by Hapnappier, who seemed to import a high percentage of the estate’s wines into Benelux countries.

Moving on, it was the turn of the Right Bank. The 1959 Cheval Blanc was spectacular and given that this bottle had been bought directly from the château via auction that comes as no surprise. This was my third encounter with this wine that last with the late great John Avery in 2011. Crystal clear in colour, refulgent even, it boasted an intense bouquet with wild strawberry and black cherries, and a touch of glycerin. The palate translates the concentration and precocity of the 1959 vintage, coming across more Merlot-driven than Cabernet Franc. It outshone the 1959 L’Evangile, different appellation (well partially if you want to be pedantic) but certainly neighbors. That is to take nothing away from another impressive wine that replicated the performance of a double magnum tasted in 2009. You had to admire the density and structure, the same richness as the 1959 Cheval Blanc but without quite the same sophistication. This wine was actually made during a tricky period for the estate, embroiled in family squabbling over proprietorship since some of the member of the Ducasse family wanted to sell L’Evangile after frost had decimated the vineyard in 1956. So, it is interesting to compare this 1959 with the 1955 L’Evangile, which would have come from much older vine stock when it was owned by Catherine Horeau. It had a very complex bouquet with pinecones and an odd but attractive scent of Chinese XO sauce. The palate was typical of 1955 Right Bank wines, exuding purity and grace, delivering a spellbinding sense of symmetry on the finish. It was a privilege to taste these two L’Evangile bottles. They are extremely difficult to find nowadays and we were lucky that both showed as they ought to.

Let’s stay with the 1955 vintage. Long terms readers will know that it is one that I have promulgated since my primordial Wine-Journal days and over the years nearly every bottle has vindicated that view. This is a bona fide great Bordeaux vintage that was under-rated for many years. Unfortunately, the 1955 Carruades de Lafite had seen better days, which can be excused given it is a deuxième vin. You can’t win ‘em all. The 1955 Latour restored order: a brilliant wine from the First Growth, again, provenance playing a key role as this came direct from the Mähler-Besse reserves. Consulting their records, the 1955 was picked on September 25, underwent a “very active fermentation” that produced rich musts comparable to 1949 and 1952. There is no messing about the nose that goes straight from the jugular: vivacious red fruit, hints of eucalyptus (a trait that I often discern on the 1945) with breathtaking focus. The palate is structured but exquisitely balances with a long deep and satisfying finish. It is a magnificent Pauillac cruising at high altitude after many decades.

We moved back to the 1953 vintage. This was a favorite amongst the British wine writers, especially Michael Broadbent. I have enjoyed some spectacular encounters, in fact, one of the greatest bottles I have ever drunk comes from this vintage, but Vinous readers will have to wait for me to retell that. The 1953 Léoville-Barton sported that fabulous old art deco label that is now used for the second label. This came from the era under Ronald Barton. As Clive Coates MW mentions, the château was in a poor state after the war with one-quarter of the vines missing, so when this 1953 was made, Ronald was still reconstituting the vineyard and making barely a penny. Yet, as I mention in my note, it conveys a sense of “faded class”. You had to ignore a nagging metallic note on the nose, but the core of fruit was extant if not as powerful as Léoville Las-Cases, with a bucolic finish that reflects the rudimentary conditions this 1953 would have been made in. The 1953 Léoville Las-Cases was better, although I have had finer examples in the past. It sported a far superior nose compared to the Barton, yet the palate seemed more fatigued than I think larger formats or other bottles might show. Returning to Léoville Barton, we later enjoyed a bottle of the 1959. Despite the vineyard having been devastated by the frost three years earlier, this is a resounding success. Cedar and scents of antique bureau on the nose, plenty of degraded red fruit and floral scents developing with time, it was just a lovely mature Claret. There was something gentle yet compelling about this Léoville Barton even if I feel it is in gradual decline.

A late addition to the line-up was the 1957 Mouton Rothschild, which was served blind and totally threw me thanks to the liveliness on the mint-tinged nose. This vintage is not common these days, forgotten between 1955 and 1959. However, it is one of those vintages that can surprise, just like this bottle. Despite a little volatility, you had to admire its density and detail after all these years. Current winemaker Philippe Dhalluin told me that this is his birth-year so I hope he has tasted this Mouton himself. It is a treat.

The stellar 1959 Palmer, unfairly in the shadow by the 1961 with the 1959 Grange, one of Max Schubert’s “hidden” vintages just visible alongside.

The final Bordeaux was the 1959 Palmer. Now, I know several mavens who argue that on its day, the 1959 can outclass the legendary 1961 though neither example I have encountered previously vouchsafed for that view. However, this bottle certainly did. Wow! The bouquet just soared from the glass with cassis and juniper berries, the palate beautifully balanced with incredible horsepower towards the bravura of a finish. Interestingly, this was made just a couple of years after the Sichel/Mahler-Besse families had acquired the neighboring Château Desmirail and incorporated part of that vineyard.

The last bottle is one that, to be honest, I underappreciated as I drank it and write my note. Too blasé. I dislike transgressing on fellow Vinous writer’s patches, so I hope Josh forgives my retelling of this important wine. Our host has one of the most enviable collections of Penfolds Grange and he poured one of the most elusive: the 1959 Hermitage Grange Bin 46, to give it its full title. It was only later that I realized that this was the last of winemaker Max Schubert’s “hidden Granges”, made when his paymasters objected and forbid the production of dry red wine since the industry and commerce was built upon fortified wines in those days. Inspired by his visit to Bordeaux some years earlier and undeterred, Schubert covertly made three vintages. It was only when they were slipped into wine shows and began picking up awards that his employers relented and an icon got the green light. Therefore, not only is this Grange extremely rare, but it holds historical significance. The 1959 was a blend of 90% Shiraz and 10% Cabernet Sauvignon and according to the label, bottled in 1960. It was just a beautiful mature wine, rich and quite candied on the nose with hints of praline and nougat, sensual on the palate, somehow conveying that Australian warmth after all these years. You just wanted to raise a glass to Max Schubert for creating a wine that decades later, stands shoulder to shoulder with the very wines he sought to emulate.

So, the night drew to a close with the Everly Brothers crooning Cathy’s Clown on the radio. If only all wines were as harmonious as those siblings’ voices. My brain is still fried by the conjurer and recounting the episode now I cannot, for the life of me, work out how he did it. Then again, tasting some of these 1950s wines after over sixty years, it is clear that some of those long-forgotten winemakers waved a magic wand to create wines that have stood the test of time. In many ways, winemakers are turning to these as reference points, predating the use of chemicals and herbicides, made in a natural way not because of predesign but simply because there was no alternative. Despite the backdrop of slowly recovering from the war, the decrepitude of some vineyards, the absence of profitability and therefore investment, the havoc wrought by the spring frosts of 1956 and the fact that few people were regular wine drinkers, it is a miracle that this golden decade provided a raft of fabulous wines that continue to offer pleasure. The finest 1955 and 1959s remain utterly sensational, the 1953s perhaps now just beginning to fade, yet still worth seeking out if provenance is assured. If only I could borrow some of the magician’s cylinders to magic these bottles out of nowhere. And now, back to thinking how he put that block of glass into my enclosed hand...

(My sincere thanks to Mr. and Mrs. A for hosting this splendid and fun night, and for those that contributed to bottles of wine worth writing about.)

You Might Also Enjoy

2008 Bordeaux: A Day In A Life, Neal Martin, February 2018

So Neal, What Can I Expect?, Neal Martin, February 2018

Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande 1921-2016, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

Larcis Ducasse Retrospective: 1945-2014, Antonio Galloni, March 2017