Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Battle Royale! Bordeaux 1961, 1982, 1990 & 1995

BY NEAL MARTIN | DECEMBER 2, 2025

Take A Ringside Seat

Like many kids, every Saturday lunchtime, I was glued to the cathode ray tube to watch ITV’s “World of Sport.” I was not interested in the speedway, darts or the 3.45 at Newmarket.

I was there for the wrestling.

Not the American version with all its razzamatazz, all those bronzed, muscle-popping bodies performing to thousands in some rustbelt enormodome. No, this was the cut-price British version that took place at Wembley Arena, a mixture of sport, pantomime and spandex. These televised bouts starred a rollcall of eccentrics that became household names, adored by millions, purportedly including the Queen and Margaret Thatcher.

There was Kendo Nagasaki, the masked ninja warrior whose identity was a mystery, a homegrown Bruce Lee without the chiselled jaw, mystique or skill. Nagasaki San was eventually unmasked as Peter Thornley from Stoke-on-Trent. Mick McManus was a pocket-sized, ferocious-looking Scotsman who flagrantly broke the rules. His catchphrase was “Not the ears! Not the ears!” as opponents targeted his cauliflower lugholes.

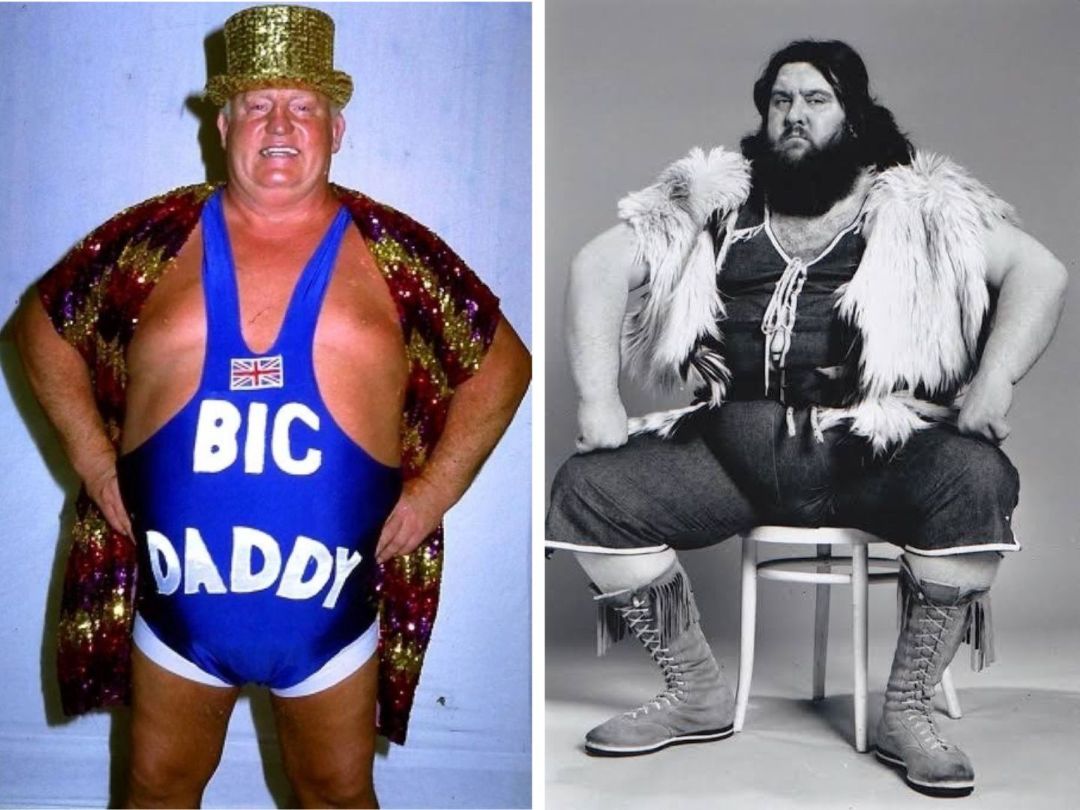

Titans of wrestling: Big Daddy and his foe in the ring, Giant Haystacks.

The “Lionel Messi” of British wrestling was Shirley Crabtree, aka Big Daddy. Yes, he really was baptised Shirley. Big Daddy was a spherical, rosy-cheeked, white-haired grandad whose body looked as if it had been inflated with a car tire pump. Poke him with a pin and he would pop. Looking faintly ridiculous in a leotard emblazoned with his moniker (sewn on by his wife), Big Daddy was the good guy. “Easy! Easy! Easy!” chanted crowds as he belly-flopped onto his defeated opponent. However rehearsed, it must have hurt.

My favourite was Giant Haystacks. Do I even need to describe his stature with that name? He made Big Daddy look small: 6’11” and even greater in width. With straggled, greasy hair and an unkempt beard, clad in a mangy fur rug, Haystacks looked like Hagrid gone to seed. Unlike Hagrid, Haystacks was the villain, the nemesis of Big Daddy. He wore a permanent snarl, the expression of someone who just opened a corked ’61 Latour. His few utterances were drowned out by raucous boos. Mr. Haystacks struck the fear of God into this nine-year-old, but outside the ring, he was a devoted family man who attended church every Sunday.

This wistful introduction is an allegory to four renowned Bordeaux vintages entering this Battle Royale to see who comes out on top. In 2025, I had a ringside seat to assess 1961, 1982, 1990 and 1995 Bordeaux at four separate dinners. Despite Bordeaux’s multiple travails, there is burgeoning interest in the market for back vintages that represent excellent value vis-à-vis en primeur and are cheap as chips compared to Burgundy Grand Crus. The 1982 dinner took place on my birthday in February at Cornus in London, the 1990s at Medlar three months later, then the 1961s at Ami restaurant in Hong Kong in September. This article was initially intended to focus on those three vintages, but the gaggle of 1995s tasted at Piccolino restaurant in October performed so well that they too deserved to enter the ring. With the exception of the 1961s, it should be noted that bottles were served single blind, usually by appellation.

Growing Seasons

For detailed information on those growing seasons, flick open my own “Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide” (revised and updated, available in all good bookshops, et cetera). Otherwise, a quick rundown is necessary because there is no template for a great vintage—it is a combination of factors that play out over the growing season.

The critical date for the 1961 vintage is May 29, when a late spring frost devastated vineyards, the earlier-ripening Merlot vines suffering most. That turned out to be the only bad news that year. The remaining season was blissfully hot, dry and sunny, which concentrated the fruit, though by “hot,” the mercury tipped 30°C, not the 40°C seen nowadays. The September harvest saw a small crop of intensely concentrated berries that begat tannic wines predestined for longevity. Sales were initially slow because merchants were still selling the large volumes of 1959.

The 1982 vintage was very different from 1961. There was no late spring frost, and flowering was quick and even, despite sporadic showers. It was again hot and dry, though August was unseasonably overcast and cool. Balmy conditions returned in September and picking commenced around September 13. Harvests were drawn out because of the sheer volume of fruit, some wineries unable to cope with the deluge of incoming bunches. Continuing heat meant that fermentation was tricky, as many châteaux lacked temperature control. Unlike the 1961s, the 1982s were approachable from the get-go and as such dismissed by cognoscenti. One up-and-coming reviewer from Baltimore thought otherwise. The rest is history.

The 1990 growing season saw localised frost damage, though nothing like 1961. Temperatures early in the growth cycle swung wildly, so there was heterogeneity in ripeness, especially the Cabernets. June was cool and rainy, and July was hotter. Excessive bunches meant that many châteaux enacted the novel practice of green harvesting. The heatwave from July 11 was one of the longest on record, with the mercury reaching 40°C and vines closing their stomata. Harvest began around September 14, though the irregularity of the Cabernets meant that the picking strung out until October 24. The vintage was well received, though sales were actually sluggish since Bordeaux lovers had splashed out on the 1989s. Sales eventually gathered momentum, and 1990 vied with 1989 as the best vintage of that period. The latter has perhaps gained a little more kudos thanks to overachievers like Haut-Brion and Pichon Baron.

The 1995 vintage came as a relief after four subpar seasons, and consequently, it was perhaps overhyped on release, neither the first nor the last time that has happened. Flowering coincided with uneven weather, but there was only a spot of coulure. The summer was warm and particularly sunny, but the drought was worrying, prefiguring the canicules (the long periods of drought that the region has seen in recent vintages_. Fortunately, there were sufficient underground water reserves to stave off hydric stress. Rain between September 6 and 12 diluted some of the Merlots, but it recharged the Cabernet Sauvignon, though berry size was small—like “peas,” according to the late Bill Blatch. The 1995 vintage was similar to 1982 in terms of a large crop.

The Wines

A dozen 1961s were assembled for the dinner held mere hours after I touched down in Hong Kong, and I’ve included a Branaire-Ducru from lunch three days later. Though 1961 is a bona fide legendary vintage, everything eventually shuffles off its mortal coil. As such, many 1961s are now cresting, peaks now visible in rear-view mirrors. Wines endowed with density and heft a decade ago have since softened and mellowed, naturally shedding their precocity. But this is destined to be a slow decline from extremely high peaks, so please do not start writing off these wines. Let them enjoy their dotage. The 1961 Palmer is a prime example. Having enjoyed several bottles over the years, what was always a profound and unapologetically elegant Margaux can now seem insubstantial, almost slight, when juxtaposed against the best First Growths. Therefore, it is important to assess it on its own merits. I appreciate its silky texture and transparency, more consanguineous to Burgundy than Bordeaux. Subject to provenance, the 1961 Palmer is not going to deteriorate at any great speed, and well-stored bottles will drink well for another 20 or 30 years.

The standouts on this evening were the 1961 Mouton-Rothschild and 1961 Haut-Brion. This fabulous duo remains undiminished by the passing of time. In fact, the Haut-Brion meliorated in the glass. Lest we forget that this was the first vintage fermented in revolutionary stainless-steel vats installed by Jean-Georges Delmas. The 1961 Latour was just a couple of steps behind. Here, it did not quite possess the astounding depth and complexity of the Mouton-Rothschild, which, to the chagrin of Baron Philippe de Rothschild, was still an unbecoming Second Growth.

Others were pertinent reminders that back in 1961, Bordeaux was less consistent than nowadays. Even revered estates did not necessarily create masterpieces. Many vineyards and wineries were little changed from before the war due to lack of investment. The 1961 Léoville-Poyferré, Pichon Baron and Lynch Bages predate their coming of age under Didier Cuvelier and Jean-Michel Cazes respectively. These châteaux needed those visionaries to grab them by the scruff of the neck, so these 1961s are instances of drinking what it is and imagining what might have been. Not so with the 1961 Ducru-Beaucaillou. Whilst it has lost a bit of density in recent years, this bottle, which had lain in the cellar of Tour d’Argent in Paris its entire life, remains a compelling Saint-Julien.

The 1982 dinner was an enticing prospect with a number of exceptional bottles. When your friend announces that he could not locate his 1982 Petrus, but not to worry because he bought Lafleur instead, you know that you are in for a great night. I have always relished the Saint-Julien wines in this vintage. Here, the 1982 Léoville-Poyferré, Gruaud Larose and my own contribution, the over-performing Talbot, were all convincing, simply delicious. The 1982 Léoville Las-Cases was a lauded wine, in no small part due to Robert Parker’s lionisation, though I never felt it was the best within the appellation. The 1982 Palmer has always been overshadowed by the 1983. This bottle was terrible, sporting a malodorous geranium scent on the nose and an unmistakable herbaceousness on the palate.

The reputation of 1982 rests on a dozen or so magnificent wines that have lasted the course. Pichon Comtesse de Lalande, Mouton-Rothschild, Lafite-Rothschild, Cheval Blanc, Trotanoy and Château Margaux all flirt with perfection, though there is now bottle variation, not least apropos Mouton-Rothschild. The 1982 Latour is the most consistent bottle-to-bottle, ditto the seemingly immortal 1982 Lafleur made by Jean-Claude Berrouet and Christian Moueix. This series of 1982s ranks amongst my vinous highlights of the year, and all of the aforementioned will continue to offer immense drinking pleasure over the next couple of decades.

Looking back, anticipation towards the 1990s was not quite at the level of the 1982 dinner, but this set of wines reaffirmed the quality of the vintage. We broached a number of wines from Saint-Julien first. Gruaud Larose, Lagrange and Léoville-Poyferré performed strongly, conveying a sense of richness and sumptuousness whilst holding on to typicité and freshness. The Léoville Las-Cases did not quite show its true potential, but this was partly because I feel it required longer decanting than the others. Only the 1990 Léoville Barton was deemed below expectations.

The next flight saw the notorious 1990 Montrose, a wine that astounds or appals, depending upon the level of Brettanomyces and your sensitivity to it. We were fortunate—this bottle demonstrated hardly any infection, thus revealing an audacious and complex Saint-Estèphe that blossomed in the glass. Neither the 1990 Lynch Bages nor Grand-Puy-Lacoste showed as well as previous bottles, so I substituted the note for the latter with another 1990 shared by winemaker Bernhard Bredell in Stellenbosch in August. Matters started getting serious with a sensational 1990 Château Margaux, one of the best from the late Paul Pontallier and maybe the best 1990 First Growth. I have encountered better bottles of 1990 Haut-Brion, fated to be unfairly overshadowed by the 1989 for eternity, whilst the 1990 Lafite-Rothschild was a pleasant surprise. I have never really taken to this particular wine, and typically prefer the 1988 amongst the end-of-decade triumvirate. This was actually the best bottle of 1990 that I have drunk.

We moved to the Right Bank with a savoury, almost Rhône-like Tertre-Rôteboeuf. The most intriguing pair was the 1990 Cheval Blanc and 1990 Beauséjour Duffau-Lagarrosse. The latter was anointed with a perfect score by Robert Parker, in retrospect, a freak wine far superior to any other vintage from this Saint-Émilion estate. Because of that score and small production, bottles are elusive. I have only tasted it once, and that was over 20 years ago. So, after 35 years, does the 1990 Duffau deserve its reputation?

Frankly, it was like yours truly challenging Giant Haystacks for a fight in the ring. The 1990 Cheval Blanc was far superior in terms of delineation and complexity. The Duffau typifies what was in vogue at that time—dense, concentrated, lush and sweet. Let me state for the record that the Duffau is impressive and thoroughly enjoyable. Still, it unequivocally could not hold a torch to the dazzling complexity of the sensational Cheval Blanc. This comparison is a reflection of how attributes of what constitutes a “great” wine have changed.

As I mentioned, I never planned for the 1995s to be included in this report. This was the second of two dinners held in London, the first apparently hampered by corked bottles and downbeat assessments. As is often the case, the wines performed supremely well in the second dinner, and except for a Smith Haut-Lafitte, we were spared any corked bottles. What I found so surprising was the exuberance and youthfulness present in 1995s—it’s easy to forget that they are already three decades old. Most still show primary aromas and flavours, the tannins having softened in recent years so that most teeter on that delicious liminal point between the primary and secondary phases of their evolution. This is an attribute of the 1995s that I had not expected. Standouts include the 1995 La Fleur-Pétrus, Clos Fourtet (made by Pierre Lurton pre-Cheval Blanc), Château Margaux and two bottles of Ducru-Beaucaillou tasted in Hong Kong and London, respectively. Maybe our group was lucky in terms of bottles and châteaux? However, these wines are relatively easy to find on merchants’ lists, and given market values, the 1995s deserve to be included with such luminaries as 1961 and 1982.

Summary

All four vintages have much to offer Bordeaux lovers, a group of wine drinkers that is sadly thinner on the ground than a few years ago. Why is that the case when these wines offer so much sensory pleasure? Are they unfashionable? Most certainly to a younger crowd seeking hipster names and labels that demonstrate cutting-edge tastes. Refusal to cellar wines long-term? Wine lovers have lost the ritual of cellaring bottles for future consumption and desire instant gratification. As such—like I have written before—many palates are no longer accustomed to the nuances of a mature wine, unappreciative of secondary aromas and flavours.

Be that as it may, Bordeaux deserves patience and time. The present-day mantra of “drink Bordeaux young because modern claret is more approachable” is understandable, but it is a false path. It is like advising Hendrix to put down his Stratocaster and play bass guitar, or Nvidia to stop producing microprocessors and instead manufacture VHS tapes. Bordeaux’s inherent ability to evolve over time and to develop profound complexity and personality at high volumes of production remains unmatched. These wines’ longevity has been Bordeaux’s USP since time immemorial. I do not begrudge consumers drinking Bordeaux after four or five years, but don’t kid yourself that you are imbibing the wine anywhere close to its peak. You are consuming its primary aromas and flavours at a time when the mark of the winemaking is more apparent than terroir, in which case, why spend all that money when you can do likewise across the numerous vastly improved wine regions across the world?

There is an ongoing re-evaluation of mature claret in vintages like these, not least when considering the cost. Some of these 1961s cost the same as a run-of-the-mill highfalutin Burgundy. As such, it might not be as cool to drink Bordeaux, but there is another dimension in terms of drinking a wine with age, a wine that has reached its notional peak. The future of en primeur is bleak, yet there is definitely an uptick in demand for mature bottles that has rekindled interest in the region. This is a conundrum that châteaux now face.

Provenance is fundamental. In my experience, it is the most vital factor, even more than vintage, producer or vineyard. Many of these bottles were bought at the time of release or sold as ex-château at auction (though what does that mean when estates are restocking their own depleted libraries from auctions themselves?). Even then, you must anticipate some bottle variation due to minuscule differences in micro-oxygen ingress through corks’ pores over long periods of time. That introduces an element of unpredictability, though I would argue it is still less unpredictable than approaching young Burgundy, as evidenced by the recent Burgfest tasting.

How to Avoid the Count

British wrestling is a quaint remembrance. Its popularity waned in the late eighties as the American WWE exposed its amateurism. It was a bit naff. Household names vanished from our screens and public consciousness. Outside the ring, Big Daddy and Giant Haystacks were best friends. Big Daddy died of a stroke at age 60, Haystacks of lymphoma at just 52. With their passing, a bit of our collective childhood died too, something I saw repeated in the States when Hulk Hogan died earlier this year. U.K. wrestling serves as a reminder of how popularity can slip away. How sticking your head in the sand can have fatal consequences. Similar sports such as snooker and darts are both thriving because they reinvented themselves to appeal to younger audiences.

Bordeaux has a historical track record of legendary vintages like no other, but for future 1961s or 1982s to enjoy consumption en masse, there must be structural changes, a rethinking, an acceptance that we are in a different vinous landscape, one that poses immense challenges.

You know what all these vintages have in common?

They were all affordable on release and rewarded consumers financially if they bought the wines en primeur. These wines enticed consumers to open their wallets and cellar bottles, eventually to share them with friends. In this way, châteaux built connections with their audiences not vicariously, but through the direct interaction between consumer and bottle. As Bordeaux teeters on the brink, it must take a long, hard look at itself and ask how it can reconnect to its lost audience. Everything must start with corks being popped. If that is not happening, then any strategy is doomed. If châteaux can engage with future drinkers who have been made to feel unworthy to drink Bordeaux—moreover, if consumers can regain appreciation of the joy of aged claret—then the crowd will begin chanting once again…

Easy! Easy! Easy!

Thanks to all those who proffered bottles at these dinners in recent months.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Hand Over the Keys: Brane-Cantenac 1928-2023, Neal Martin, September 2025

A Woman’s Touch: Lafleur 1985-2022, Neal Martin, September 2025

A Century of…Fives, Neal Martin, June 2025

Event Horizon: Bordeaux 2024 Primeur, Neal Martin, May 2025

Intellect & Senses: Bordeaux With Time, Neal Martin, March 2025

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Angludet

- Beauséjour Duffau Lagarrosse

- Beychevelle

- Branaire-Ducru

- Certan de May

- Château Margaux

- Cheval Blanc

- Clos Fourtet

- Cos d'Estournel

- De Malle

- Ducru-Beaucaillou

- Grand-Puy-Lacoste

- Gruaud Larose

- Haut-Brion

- Lafite-Rothschild

- Lafleur

- La Fleur-Pétrus

- Lagrange

- La Mission Haut-Brion

- Latour

- La Tour Haut-Brion

- Laville Haut-Brion

- Léoville Barton

- Léoville Las-Cases

- Léoville Poyferré

- Lynch Bages

- Montrose

- Mouton-Rothschild

- Palmer

- Pichon Baron

- Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande

- Pontet Canet

- Talbot

- Tertre-Rôteboeuf

- Trotanoy

- Yquem