Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Enigma Variations: Lafleur 1955-2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | NOVEMBER 1, 2018

Commencing our vinous odysseys, we set out on our own individual paths of discovery. Some wines become familiar right away; others remain out of touch. Budding oenophiles embark upon “the chase,” hunting new growers and filling gaps in vintages never tasted. When I began my own journey, I rarely had two pennies to rub together, and when I did, they were spent on vinyl records, wine or food, in that order of priority. Circumstances, luck and dogged determination introduced many Bordeaux wines to my palate, but one château eluded me: Lafleur. It was the cunning fox, always out of sight, always just over the horizon. Its elusiveness only enhanced its enigma and my yearning to track it down.

I finally succeeded during en primeur 2003. Jacques Guinaudeau was friendly and charismatic, with a magnificent bushy mustache long overdue effeuillage; he looked like a North Sea fisherman who had just taken off his sou’wester. His wife Sylvie was so down-to-earth that it was difficult to reconcile the fact that she co-owned one of the most famous estates in the world. Their son Baptiste was in tow, sporting long, tousled hair and dressed as if he had come directly from a skateboard park. He was learning the ropes from Jacques, and so he and I chatted about wine – and incidentally discovered a mutual appreciation for the Beastie Boys. Baptiste has come a long way since then. I recently drove past Lafleur and chanced upon him standing in the road, deep in discussion with a foreman, poring over plans for their near-complete new cuverie, the biggest change to Lafleur since its formation. Baptiste calls the shots these days, along with his better half Julie, but he still has long hair and a soft spot for Brooklyn’s finest rappers.

Since that first encounter with Lafleur, my palate has been blessed with numerous vintages over the years, including a memorable vertical back to the 1920s held in Attersee, Austria, literally the day before the deadline for my Pomerol book. I actually delayed publication because Lafleur was such a cornerstone of that work. Retrospectives that extend past 1982 are few and far between, in no small part because the Guinaudeaus possess no library stock or, for that matter, any records beyond that year. This only deepens the mystery surrounding the wines that were made by the “two little birds,” the nickname I gave to Marie and Thérèse Robin, the sisters who owned and ran Lafleur from 1946.

This article covers wines from both the Robin and the Guinaudeau eras, tasted in two separate Lafleur retrospectives. The first formed part of Omar Khan’s International Wine & Business series of tastings held at Ten Trinity Square in London, ranging from the 1950s up to the 1999 and embracing less frequently spotted off-vintages and undisputed legends. The second was held at Christie’s auction house and attended by Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau. Here the focus was post-2000-vintage releases of both Lafleur and Pensées de Lafleur. For completeness, I have supplemented these notes with several culled from my Pomerol book.

The magnificent lineup of Lafleur back to the 1950s at Ten Trinity Square

History

In 1872, Henri Greloud purchased a farmhouse and a small area of land known as Domaine de Gay. He decided to keep one block of vines separate from the remainder of the vineyard and christened it Lafleur. (In the 1893 edition of the Féret guide, Lafleur already commands high prices compared to its peers.) When Henri died in 1900, his son Charles inherited Lafleur, while his other son, Edgar, was given Château Grand Village in Mouillac. In 1915, Charles died childless, and Edgar’s daughter and her husband André Robin inherited Lafleur and Le Gay. André Robin tended the properties up until his own passing in 1946, whereupon the vineyards landed in the aproned laps of his daughters, Marie and Thérèse. The sisters were two peas in a pod, neither of them betrothed despite several suitors, and leading frugal but seemingly contented lives, cycling between Libourne and Pomerol, pottering about the vines and nattering with Mme. Loubat at Petrus. Neither Marie nor Thérèse really knew much about winemaking, and they famously allowed their chickens to cluck and poop around the cellar, so it was not the most spotless chai in Pomerol. Their naïveté meant they had no option but to adopt their father’s tenets, and apart from allowing poultry to wander at will, their one basic rule was to pick Lafleur after Le Gay. That unwitting application of the practice of late harvesting is one reason why some postwar vintages became legends.

Though prone to inconsistency, the quality of Lafleur was in no doubt, so that it gained a small but loyal following. There was little overseas interest, apart from the Benelux countries, where Pomerol wines were presciently appreciated, and Lafleur never cracked America, where Jean-Pierre Moueix was pouring Petrus and building its reputation. When the sisters became old and infirm, they asked Christian Moueix and Jean-Claude Berrouet to take charge of the vineyard and vinification. The pair oversaw the astonishing 1982 Lafleur and an outstanding follow-up 12 months later. But when Thérèse died in 1984, Marie Robin asked Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau, descendants of the Greloud family now ensconced at Grand Village, to take stewardship.

Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau in the Christie’s boardroom in May 2018

The Guinaudeaus hit the ground running with the divine 1985 Lafleur, but there was a lot of work to do, not least replanting almost one-quarter of the vineyard, mostly the Merlot vines. Marie Robin passed away in December 2001, and speculation ensued: who would purchase Le Gay and Lafleur? It transpired that the Guinaudeaus sold their rights to Le Gay to the late Catherine Père-Vergé, enabling them to finance the acquisition of Lafleur. Though Baptiste Guinaudeau and his partner Julie have slipped into the driving seat, Baptiste’s parents remain present. Lafleur has always been a family concern. Many tastings were accompanied by the soundtrack of their daughters playing on the swing outside, once or twice proffering their own views on the latest barrel sample – after all, you’re never too young to start your vinous education. For a period, the young family called Lafleur home, although the confined space and growing offspring meant that they moved out a couple of years ago. Probably a good thing, too, now that the builders have moved in to construct the new winery. The next chapter is being built brick by brick.

The Vineyard

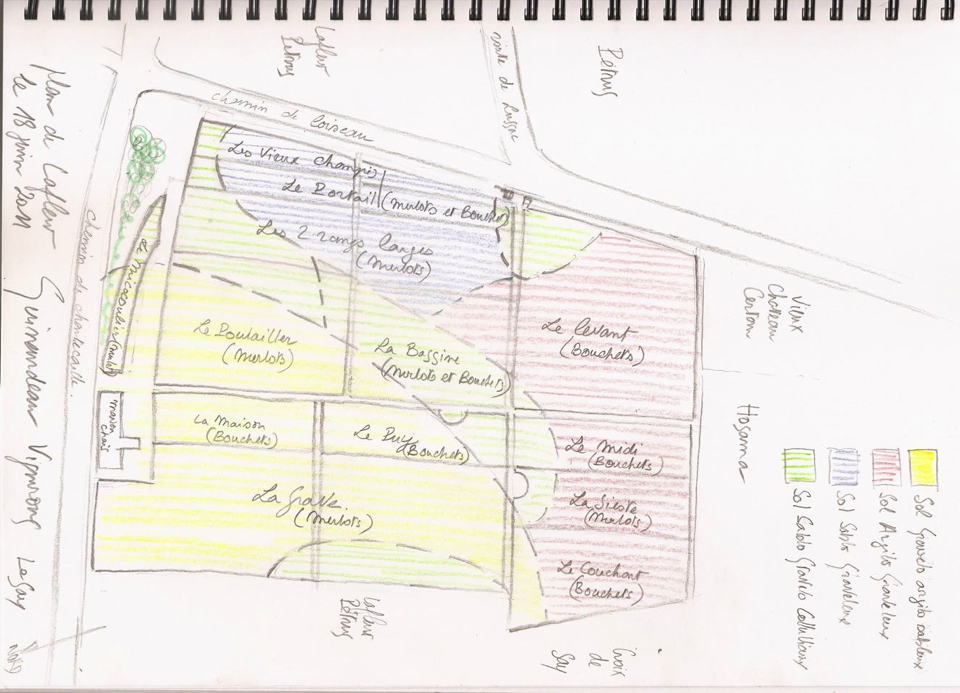

Lafleur is a small vineyard even by Pomerol’s standards; at 4.5 hectares, it covers less than half the area of neighboring Petrus. But despite its diminutive size, Lafleur is actually a complex mosaic of four complementary soil types: gravelly toward the eastern flank, gravel over clay toward the north and west, and sandy/gravelly toward the south, plus a sandy crescent of silt-like soil that is the base for Pensées de Lafleur. Lafleur’s unique selling point is the contribution of Cabernet Franc, which grows at higher altitude here than in any other Pomerol cru and represents around half the vineyard plantings. Baptiste Guinaudeau found nursery clones to be unsatisfactory for Cabernet Franc, so now they are replanted through sélection massale.

The original color drawing of Lafleur that Jacques Guinaudeau composed for my Pomerol tome

The harvest team picks block by block to obtain optimal ripeness, and the fruit is sorted both in the vineyard and on a sorting table. After alcoholic fermentation, the blending is done around February with the sage advice of Jean-Claude Berrouet. Lafleur is usually raised in a modest one-third new oak, mainly from the Darnajou cooperage. The final blend is around 60% Merlot and 40% Cabernet Franc, although recent vintages have been closer to an equal balance between the two, partly due to improvements in the quality of the Cabernet Franc via replanting, but also because of lower Merlot yields. Production is usually just 1,500 cases, including Château Lafleur and Pensées de Lafleur, the “second wine” introduced in 1987 after the poor growing season produced fruit deemed unworthy of the Lafleur label.

International Business & Wine Vertical 1955 – 1999

You will find vintages back to the 1920s, but I will narrate only those wines shown at the two recent verticals. The following wines were all poured at the International Wine & Business vertical in London.

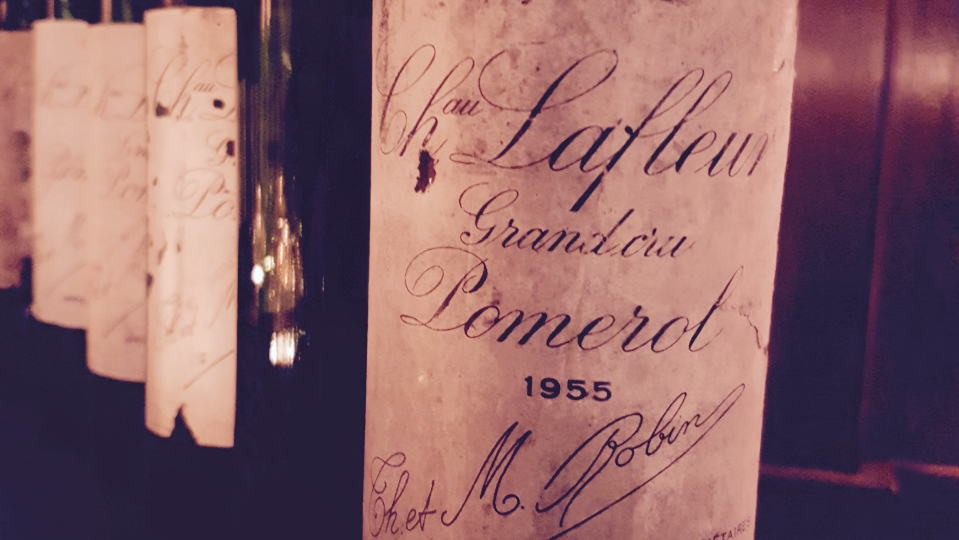

The 1955 Lafleur was the catalyst for my interest in this Pomerol. When I encountered it in 2001, it was the first mature vintage I had tasted, and it deepened my curiosity and appreciation. Seventeen years later, this “senior citizen” still makes a splendid showing. It is a testament to the skills of the Robin sisters’ naïve yet astute winemaking and to a vintage that has blossomed in recent years. Well-kept examples will continue to offer rustic delight, if not the pedigree of the stupendous 1950 Lafleur, one of the greatest wines of the 20th century. The 1955 deserves a round of applause – but not too loud, lest you frighten it. In 1956, the vineyard was devastated by the late spring frosts, though rather than uprooting damaged vines, the Robin sisters pruned them down to the trunks, praying that they would regrow. Fortunately, many of them did. The 1967 Lafleur hails from an excellent Pomerol vintage, although it is nowhere near the quality of the outstanding Petrus. It is now rather bucolic and drying out and should be consumed soon. To be frank, I was hoping for a little more. The 1972 Lafleur is one of the very few vintages that up until this point I had never tasted. It was a rotten season for all winemakers and although the wine is rather threadbare, it certainly should not be dismissed. Putting it prosaically, unlike the 1977, I finished my glass of 1972.

The monumental 1975 Lafleur is proof that the Robin sisters could create a formidable Pomerol when the wind blew in the right direction. This candidate for wine of the vintage is bestowed with almost unfathomable depth, like peering into a wondrous bottomless pool. Well-stored bottles will continue to amaze, although they are getting very difficult to find. The 1976 Lafleur is volatile on the nose and overcome by that summer’s notorious heat, presenting a hard, mealy finish, while the 1977 Lafleur is one-dimensional and no more than a curiosity. The 1978 Lafleur saw the sisters’ triumph with a standout of that vintage. I have enjoyed the 1978 several times, and this bottle was up there with the best: ferrous on the nose, beautifully balanced, floral and bridled with an almost Burgundian finish. Bottles of sound provenance continue to warrant superlatives.

There follows an interregnum during which Lafleur was run by Christian Moueix and Jean-Claude Berrouet. The 1982 Lafleur remains an Everest of a wine, probably the best Right Bank of that pivotal vintage and, ironically, superior to Petrus. The bottle at Ten Trinity Square in London flirted with perfection, and then, a few weeks later, another bottle at Cipriani in Hong Kong totally nailed it, flooring me with its structure, precision and purity. The 1985 Lafleur is a vintage that I had not encountered for some years, though my memories glow with fond recollection. I crossed my fingers that this bottle would live up to expectations, and it was an absolute knockout, perhaps the best I have come across. Glorious! With a menthol-tinged nose, unerring symmetry on the palate, and enormous depth and grace on the finish, this is Lafleur in full flight. Yes, the ‘82 is more impressive, but if you invited me out for dinner, I might ask if we could drink the ‘85. The 1986 Lafleur came from another bottle opened at the aforementioned lunch at Cipriani in Hong Kong. It has never been a top-drawer Lafleur, but then again, 1986 was not a great Pomerol vintage. This bottle had held up well after 32 years, but it was austere and earthy, missing the charm and fruit intensity of the previous vintage. Don’t write off the 1988 Lafleur, which was perhaps the most surprising vintage at the International Wine & Business tasting. I had forgotten how well this has matured. Such substance here, much more satisfying than Petrus, perhaps less rigid than it once showed and, at 30 years, à point. Is it the Right Bank wine of the vintage? Quite possibly.

The 1990 Lafleur replicated its performance at the Le Pin/Petrus/Lafleur dinner. This is a wine I adore, although it has lost some of its luster in recent years, as the 1989 exited its slipstream and glided past. The 1990 remains a great Pomerol, but I feel it may have slipped from its pedestal with age. “The 1993 Lafleur makes me think of the wines made by the Robin sisters,” Jacques Guinaudeau remarked when we discussed this vintage. To be honest, I was rather disappointed by the showing here; the wine was brittle and dry toward the finish, possibly beginning a downward slope. There might be superior examples out there, but this bottle was unappealingly austere compared to those imbibed a decade ago. I preferred the fabulous 1995 Lafleur, which displayed a potent meaty character on the nose and an expressive Cabernet Franc presence. Despite its age, I would let it blow out the candles on its 25th birthday cake before opening. The 1997 Lafleur is a useful off-vintage that is always intriguing to revisit. Jacques cited it as a year when they began to change their vineyard practices. I find the 1997 a little fatigued, with suggestions of some dryness creeping in, making it a rare example of a Lafleur born without longevity. The 1998 Lafleur is a sexy wine, but I cannot remember another bottle displaying such mineralité, almost flintiness, on the nose. This is a big, demonstrative but compelling Lafleur that probably needs another couple of years in bottle. Subtle it is not—but then again, show me a 1998 Right Bank that is. Meanwhile, the 1999 Lafleur is a favorite of mine, the off-vintage I would choose over, say, the 1993 or 1997. Sandwiched between two fêted seasons, the 1999 is splendid: beautifully balanced and surprisingly vigorous, a little Left Bank in style, with a graceful finish. It is drinking supremely well at nearly 20 years of age, and it remains the dark horse of the decade.

The Wines: Christie’s Lafleur Masterclass (2000-2015)

We now move into the 21st century, courtesy of a masterclass held at Christie’s that preceded a major auction of Lafleur and was attended by Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau. Spanning 2000 to the present day, this era saw a gradual passing of the reins to the next generation. In a region where transitions can be fraught with internecine family fallouts and lawyers mediating between avaricious shareholders, the seamless segue between generations has been refreshing and welcome. In fact, I suspect that a lot of people have hardly noticed. Of course, the only place where Baptiste has not yet followed his father is in terms of his mustache.

We tasted the wines from youngest to oldest, but I continue our passage through time going forward. So we commence with the immaculate 2000 Lafleur. Jaws had to be picked up off the floor, because this is a copper-bottomed, astounding Lafleur— a modern-day 1982 with a 60-year lifespan. I can find no fault. One hundred points. Next! The 2001 Lafleur is destined to be overshadowed by its millennial predecessor, but Pomerol surpassed itself in this vintage and many Pomerolais favor their 2001 over 2000. “It was a classic vintage,” remarked Guinaudeau, “and a late harvest, so all the picking was done in October. The maturity had come slowly and the fresh nights helped with acidity.” This is a marvelous wine that is, once again, beautifully balanced, with less grippiness and density than the 2000 and revealing judicious spiciness that elevates the finish. The 2003 Lafleur is a wine that I sincerely want to love, to show that terroir triumphed over that season’s infamous merciless heat. Jacques Guinaudeau explained: “In 2003, there was incredible heat but not necessarily dryness. The north-south orientation of the vines helped protect the grapes. We had to discard some west-facing Cabernet Franc that became shriveled, but I remember that at the peak of the heat wave, the Cabernet Franc had not changed color. The Merlot was more complicated because the sun made the grapes a little jammy and confit. I didn’t know what it would become at the time, and I find it atypical.” That last word explains my tepid reaction to this Lafleur. I am habitually critical of wines whose typicity is smothered or erased by a growing season, and so, while the 2003 Lafleur is actually better than many of its Pomerol peers, I prefer the 1999 or 2007.

Some of the high points at the Christies’ tasting

The 2005 Lafleur is a behemoth. It stands like a dazzling cast-iron monolith on the Pomerol plateau. “We had very little to do thanks to nature in 2005,” commented Sylvie Guinaudeau. Having tasted the 2005 numerous times, I have a niggling suspicion that this ex-château bottle was not quite firing on all cylinders, yet its structure and density commanded respect. The 2000 might have a little more precision, but I love how the Cabernet Franc just soars on the prolonged finish here. The 2005 needs several more years for the tannins to soften, and maybe double that to truly experience it at its peak. The 2007 Lafleur is a very useful off-vintage that reflects viticultural improvements. A similar growing season a decade earlier would surely have produced an inferior wine. “In 2007, more Cabernet Franc started going into Lafleur, and this has improved quality in recent years,” Jacques Guinaudeau remarked. The 2007 seems more approachable than the 2006 or 2008 and with a couple of years in bottle, it will be a fine Pomerol with a 20-year lifespan. The 2010 Lafleur merits a string of superlatives: an astonishing yet unapologetically backward Pomerol redeemed by a silky texture thanks to its super-fine lattice of tannin. In times gone by, this would have been an unapproachable leviathan cellared for grandchildren, instead of a wine that needs around 15 years in bottle. It will become a benchmark Lafleur in the same vein as the 1982 and 2000.

“In 2011 the vineyard suffered water stress, so the berries were small. In fact, it was one of the smallest harvests ever at Lafleur,” Guinaudeau explained. To be frank, I am not the biggest fan of the 2011 Bordeaux vintage, yet this has long been a standout in a mediocre year, with a captivating sous-bois scented nose and an arching structure that is uniquely Lafleur. The 2013 Lafleur obviously comes from a maligned growing season, and the entire vintage was picked late in October. “In 2013 there was some vine stress that blocked maturity, so the alcohol level is low,” Guinaudeau advised. While 2013s are constantly dismissed, the truth is that there is a clutch of commendable wines, Lafleur undoubtedly among them. No, it is not a long-term wine, and the season precludes the complexity of the 2011, yet there is plenty of enjoyable sappy red fruit and commendable balance. Finally, the 2015 Lafleur is a nascent legend only just beginning to fire its motors. It has a gorgeous bouquet, pure and enticing, offering layers of truffle-tinged red fruit and again, that cathedral-like tannic structure that guarantees its longevity. Is it up there with the very best Lafleur vintages? Not quite, but it is only a hair’s breadth away.

We were also treated to some back vintages of Pensées de Lafleur. “It used to be the second wine of Lafleur,” commented Jacques Guinaudeau during the Christie’s tasting, “but today Pensées de Lafleur is more a different expression of the vineyard.” The 2000 Pensées de Lafleur demonstrates that it can easily give 20 or 30 years of drinking enjoyment, still vital and full of beans after nearly two decades. The 2010 Pensées de Lafleur is immense, probably the best I have ever tasted, and offers an attractive and less expensive alternative to the Grand Vin. In fact, it is better than many Pomerol Grand Crus.

Final Thoughts

When I was researching Lafleur for my Pomerol tome, Jacques Guinaudeau commented that however much information I might discover and however deep I might delve, Lafleur always keeps secrets. That is true; the more you know, the more ignorant you realize you are. Lafleur is not a Pomerol with mass appeal, and it rarely conveys the comeliness and warmth of Petrus or Vieux Château Certan. It can be categorized with l’Eglise-Clinet or Trotanoy: Pomerols that are introspective or even curmudgeonly in their youth and demand bottle age, patience and a cool, dark cellar. Without question, Lafleur requires at least a decade in bottle for the tannins to soften, for the Merlot and Cabernet Franc to marry, and for the crucial secondary aromas and flavors to develop at their own pace. In that respect, perfect vintages to drink now are those in the 1980s rather than the 1995 or 2000, although I might make an exception for the 1999. When you experience a Lafleur at the peak of its mighty powers, it is seared into your memory, and its profound complexity can leave you speechless. And there is always that crucial element of every great Lafleur: a seasoning of enigma.

See Wines From Oldest to Youngest

You Might Also Enjoy

Where Value Lies: First Look At 2016 Bordeaux, Neal Martin, October 2018

Fairest of Them All: Cos d’Estournel 1928 – 2015, Neal Martin, October 2018

Sharing Alike: Petrus 1947 - 2015, Neal Martin, September 2018

Aiming High: Haut-Condissas 1997–2015, Neal Martin, August 2018