Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Balloons, Mermaids & Margaux: Château Giscours 1938-2023

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 3, 2025

Unless you’re a politician, then we all make mistakes. Even Jesus made mistakes. That is what made him human. Mistakes make us who we are—literally, in cases where excess alcohol is involved. We learn from our mistakes. Wine producers are no different, even if there is an unwritten law that forbids admission until a century later. Of course, wine critics never make mistakes. Our judgments are 100% correct. It’s the wine that got it wrong.

Alas, ripping the heart of your vineyard out and replanting with a less optimal variety is an action that cannot be remedied overnight. Even ChatGPT can’t sort that one out. It takes years to accept the error and even longer to resolve. This transpired at Giscours in the late seventies and eighties, at a time when Merlot was all the rage and was planted in prime land geologically and pedologically suited for Cabernet Sauvignon. General Manager Alexander Van Beek oversaw the gargantuan task of rectifying that mistake. Last year, he invited me to the château for a vertical of no less than 40 vintages. These wines tell the story of this Margaux estate with all its highs, lows and back to recent highs. Compared to its Bordeaux brethren, it has not been a smooth ride at Giscours, but as the saying goes, what tests you, makes you.

Comte de Pescatore purchased Giscours in 1845.

History

The first written reference to the Giscours property dates to 1330 and refers to a fortified keep. But the catalyst really dates to November 1552 when a wealthy draper, Pierre de Lhomme, acquired a maison noble called Guyscoutz from Gabriel Girault, Seigneur de la Bastide, for the princely sum of 1,000 livres. This was long before van Beek’s compatriots drained the Médoc’s boggy marshes, and yet, Lhomme still managed to cultivate a few vines. Come the French Revolution, Giscours had passed to Mon. de Saint Simon, though he scarpered off to Spain once he heard the guillotine being sharpened. After being confiscated as a bien nationale, in 1795, the estate was sold to two Bostonians, John Gray Jr. and Jonathan Davis. To the best of my knowledge, the pair represent the first American proprietors in Bordeaux, and one can speculate whether they were inspired directly or indirectly by Thomas Jefferson’s forays into the region several years earlier. The partnership lasted 30 years, whereupon the property was purchased by Parisian banker Marc Promis, whose name forms the appendage to his other property, Rabaud-Promis, in Sauternes.

Befitting a grand estate, architect Eugene Bühler designed the neo-classical château in 1837, subsequently joined by a sprawl of outbuildings constructed by the Cruse family, plus a narrow lido with a statue of a mermaid at one end (an emblem that originates from an Irish owner who put this part of his family crest on the label, hence the name of the second wine, Sirène de Giscours). Promis sold the estate for 500,000 francs in 1845 to Comte de Pescatore, a wealthy Parisian banker. In 1855, Giscours celebrated its status as a Third Growth, though it was a bittersweet occasion, as Pescatore passed away around the same time. In 1870, the year that the Franco-Prussian War broke out, two Bordeaux merchants, Gambès and Barry, drank Giscours in a hot air balloon at a height of 2500 meters. According to newspapers, flying above Prussians troops, the pair threw one bottle from the nacelle with a note that read, “Delicious dinner, excellent Château Giscours, and bon appetite.” I really hope that story is 100% true.

Then and now. A photo of the main château from the 19th century and one taken by yours truly upon departing the tasting last year.

Pescatore’s nephew ran the estate until 1875, whereupon Edouard Cruse, scion of the famous merchant family, bought the property for a colossal one million francs and set about landscaping the gardens that he dedicated to his first wife, Suzanne Baour. During the latter half of this century, under the Pescatore and Cruse families, the vineyard was managed by renowned Polish agricultural engineer Pierre Skavinski, and the resulting uptick in quality sealed Giscours’ reputation. Skavinski deserves a sainthood for his services to Bordeaux. He also invented a new kind of plough in 1860 and undertook pioneering anti-mildew trials in 1882.

By 1890, Giscours had expanded to a sizeable 240 hectares, of which around 65 hectares were under vine. Cruse passed away, and his second wife, Marguerite Guestier-Cruse, inherited the estate. Giscours subsequently passed to her children, though either due to disinterest or an imbroglio with the inheritance, they sold the property to Emile Grange in 1919 for 800,000 francs—less than what the Cruse family had paid due to economic malaise after the Great War. Nevertheless, English writer Edmund Penning-Rowsell waxed lyrical about the château’s wines of the twenties, especially the 1924 and 1929.

Alas, like so many Bordeaux estates, the vineyard dramatically slid into disrepair during the thirties. Its reputation declined to the extent that by the Second World War, the château lay abandoned. Like peace, its survival hung by a thread.

In 1946, Giscours was acquired by four people: Mon. Bénésis, Mon. and Mdm. Mazard and Mon. Menzer, a property owner from the Algerian town of Rovigo, now known as Bougara. Together, they formed a company uninspiringly named Château Giscours. The following year, they began working with another Algerian, Nicolas Tari, who increased his shareholding piecemeal, no doubt haggling for discounted prices given the estate’s precarious condition. At its nadir, just seven of the almost 80 hectares of vineyard were productive. That explains why vintages from the post-war period are so elusive. By 1952, Tari owned the entirety of Giscours, allowing long-overdue renovations to commence. His investment predicated the golden era of the sixties. At this point, the vines comprised around 65% Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc, 30% Merlot and 5% Petit Verdot.

A very cool-looking Nicolas Tari (center right) at Giscours.

Tari’s son, Pierre, took over the day-to-day operations in 1970, having dabbled with poetry (don’t we all?) and joined the army. Pierre Tari heeded the “call of the vine” and enrolled for a degree in oenology. Part of the key to the château’s success at the time was the low yields, not a common goal in those days. According to writer Humbrecht Duijker, Giscours was cropped at 30.11 hl/ha between 1964 and 1973, a figure below many other properties. The first half of the seventies saw continued success thanks to the advisory dream team of Professor Henri Enjalbert, Pascal Ribéreau-Gayon and Émile Peynaud. The construction of a 12-hectare, ten-meter-deep lake enhanced drainage by lowering the water table, as well as moderating temperatures and, of course, looking pretty.

Clouds were gathering on the horizon. During the eighties, quality took a downturn after Tari pulled out his Cabernet Sauvignon vines and grafted Merlot, a variety more suited to clay than gravel. Giscours was not the only estate to do this. It takes mere minutes to bulldoze a vine but years to recognize and accept an error, replant swathes of land and wait decades until it reaches maturity, details of which are explained henceforth. Suffice it to say that vintages throughout that decade received a tepid reception. To compound their woes, the Tari family set up an exclusive distribution company that gave them more control yet deprived Giscours the exposure that comes from selling on the Bordeaux Place.

The Jelgersma Era

In 1995, Giscours was sold to Dutch businessman Eric Albada Jelgersma, whose wealth allowed him to also acquire Château du Tertre. It was not a straightforward acquisition by any means. Without entering into a quagmire of legalese, essentially, Eric Albada obtained part of the vineyard land directly from Nicolas Tari, however, around 70 of 160 hectares remained with other members of the Tari family under a long-term lease to Albada. It was ostensibly a fermage agreement, more common in Burgundy. Apparently, members of the Tari family did not see eye-to-eye, complicating matters further and stymying decision-making. Nicola-Heeter Tari continued to reside at the property after the acquisition, an arrangement that confused consumers and media alike. Who was the de facto owner? Perusing the French press of that time, there is a simmering antagonism towards Jelgersma—who was regarded as an outsider—and an underlying sentiment of wishing to see him fail.

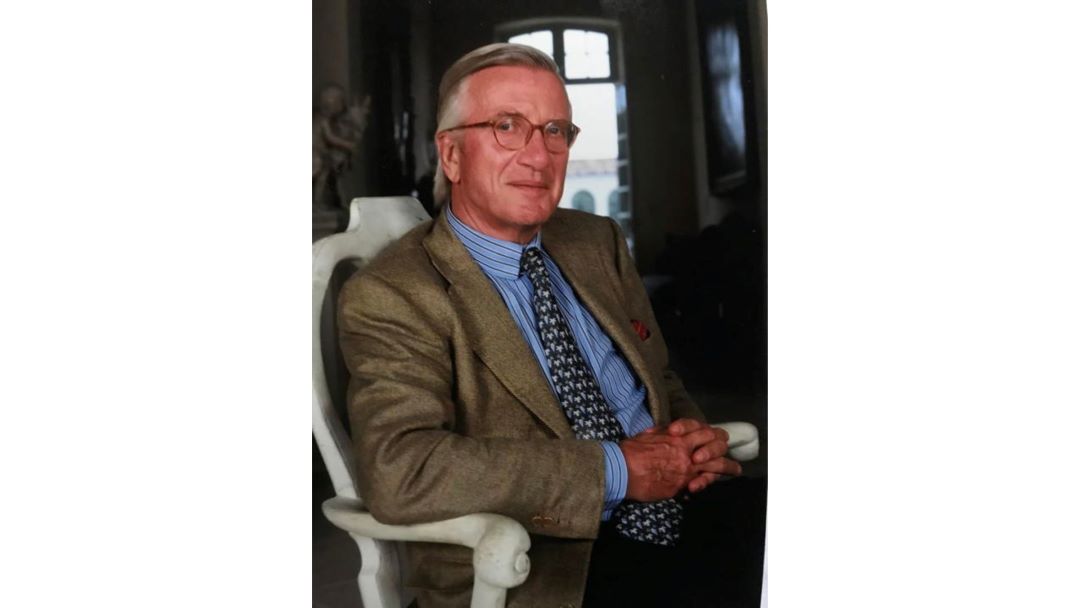

Eric Albada Jelgersma acquired the Margaux estate in 1995.

This schadenfreude was about to hit pay dirt. In 1999, scandal broke when two employees, the cellar master and a consultant, were indicted by fraud inspectors, accused of blending fruit from their adjacent two-hectare Haut-Médoc vineyard known as La Hourringue into the 1995 Sirène de Giscours. Readers should note that the Grand Vin was not implicated. There were rumours of blackmail against Jelgersma, and in a BBC interview, claims from his lawyer that a letter threatened to release damaging information. The scandal sent ripples through the trade. Was this an isolated case, or was skulduggery afoot elsewhere? The episode ended in the courtroom with a fine, since there was no denial of malpractice. As if to compound all the tragedy and ill fortune surrounding the estate, in 2005, Jelgersma suffered a yachting accident that left him paralyzed. Being wheelchair-bound and in poor health did not prevent him from attending events and making speeches. I was moved to witness one myself several years ago. Jelgersma passed away in 2018 at the age of 79, whereupon his children, Denis, Derk and Valérie, took over the estate.

Despite this tumult, the château continued to produce wines, and a new winemaking team was introduced under the management of Van Beek. I have known Van Beek for my entire career, his vinous odyssey starting just a year before my own. Tall and impeccably well-mannered, always smartly attired with an uncommon sense of humour, Van Beek has been a model ambassador for Giscours over almost three decades—as such, one of the longest serving in Bordeaux.

“I grew up in Holland in a small village near Den Haag called Wassenaar,” Van Beek told me. “At 12 years old, I went to Austria for two years, a ski school near Salzburg, returning to complete my schooling in Holland. But I missed the mountains, and seeking a more international environment, I went to Switzerland, where I graduated with a master’s degree in Geneva.”

I asked if he could remember his first day at Giscours.

“It was September 7, 1995 when I came to meet General Manager and President Eric Albada Jelgersma, who I had known my entire life. ‘Bienvenue à Giscours,’ the team said. ‘Now you will learn about wine. Tomorrow, you start in the vineyards, then you will follow the winery during harvest.’ On the first evening I had dinner with them at Le Lion d’Or. It was a great moment and a great experience, one filled with inspiration, excitement and an unforgettable sense of responsibility. It was the start of a remarkable adventure."

Old hands at Giscours gave Van Beek a frosty reception. Caught in the crosshairs, their noses were put out of joint that a young upstart, not even a compatriot, was charged with changing the outmoded modus operandi. At that point, some parcels were missing 45% of the vines. “My first job was to complanté 130,000 vines. Plus, I had to redo the trellises and stakes for 75 hectares in a single year [1996]. The winemaker from Citran came to visit and told me that it would be impossible to complete in a year.” At the time, the incumbent staff were being paid by the original planting density, so obviously, it was not exactly in their interest to increase the number and, therefore, the amount of work. In addition, the interpolated young vines meant that within single plots, fruit could mature at different rates, resulting in variable quality. “We had to harvest on three different sequences and dates to be sure to pick with optimal maturity and obtain the precision of tannins we aim for,” Van Beek explained. “Therefore, our vines are marked by their age for the harvester to follow easily.” In addition, the 1995 Giscours had to be matured entirely in new oak because there had been no barrel rotation program.”

General Manager Alexander Van Beek with the lineup for our tasting.

The Vineyard

Giscours is one of the Médoc’s largest estates. In fact, someone once told me that there was an airplane landing strip located within its grounds. Was that true? That would make it more convenient than landing at Mérignac. Van Beek told me that the Taris had a very small strip for lightweight aircraft around 40 years ago, though this land is now planted with vines.

Located in the communes of Labarde and Arsac, the vineyard belongs to the Margaux geographical subgroup that includes Siran and Dauzac. Van Beek takes a holistic approach and views the estate as a single ecosystem that includes not just vines, but forest, springs, meadow, grazing for farm animals, biological corridors and hedgerows, all coexisting and interacting with each other. This helps to steady the vines that face greater climatic extremes and unpredictable weather events. Like all great estates, the vines occupy gravel croupes, three in this instance, that were deposited during the Quaternary Period. They are known as Petit Poujeau, Grand Poujeau and Cantelaude and rise approximately 20-meters and run in an east-to-weste orientation. The entire estate covers almost 300 hectares, including verdure and woodland, with 100 hectares under vine compromising 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 3% Cabernet Franc and 2% Petit Verdot, plus another 60 hectares under the Haut-Médoc appellation planted with 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 39% Merlot and 6% Cabernet Franc. These figures are different from those you might read in textbooks due to the replanting of Cabernet Sauvignon.

“According to our property soil analysis established by Kees van Leeuwen in 2008, we decided to replant different plots,” Van Beek told me. “Having looked at this map, [the late] Denis Dubourdieu described our soil as one of the most homogeneous terroirs/soils in the Médoc area. Our objective was to help our historical vines get back on track to achieve the perfect conditions for production. Then, we worked very hard to find the true personality of each plot, to seek the perfect harmony between grape variety, rootstocks and soil, which was essential to define a more precise and unique style whilst remaining respectful to its identity. The soil map helped us a lot in that way.”

Delving a little deeper into the technical aspects of the vineyard, since taking over the running of the estate, rootstocks have been selected according to their ability to force roots deeper into the gravel soils in order to express the terroir, mainly Gravesac and 101-14. Pruning techniques were also implemented in collaboration with a specialised Italian team from the University of Florence in order to enhance sap flow and ward off trunk disease. Half the vines were converted to biodynamic in 2008. Dubourdieu came on board in 2010, and Van Beek credits Dubourdieu with enhancing finesse with the Petit Verdot and in terms of controlling power. In 2019, the team started to measure the stress in the vines to examine differences between the young and old stock and began harvesting each at the optimal date of maturity, for which there can be up to two weeks of difference.

“Our philosophy goes far beyond a list of chemical treatments. We stopped using herbicides, insecticides and harsh chemical products a long time ago. Instead, we rely on biocontrol methods such as sexual confusion to naturally limit pest populations, and we provide shelters for birds and bats that are natural predators of harmful insects. We aim to reduce the monoculture effect by planting cover crops between vineyard rows. These crops nourish the soil, retain moisture and protect the land, creating a stable and self-sustaining agro-ecosystem. Our approach is tailor-made for Giscours, adapting to the specificities of our terroir and the challenges of each vintage. We work to maintain biodiversity across our entire ecosystem by ensuring that all elements of our landscape interact harmoniously. This includes creating biological corridors through hedgerows, forest edges, and cover crops to promote the movement of wildlife and beneficial insects. Landes ewes graze in the vineyards to manage grass and contribute to soil fertility. We also preserve genetic biodiversity by propagating old vines through massal selection and using our own indigenous yeast discovered in the Giscours ecosystem. This yeast is now used in our winemaking process to reinforce the connection between our wines and our terroir’s natural microbiological environment. This regenerative agriculture approach reflects our commitment to restoring and enhancing the natural balance of our vineyard, ensuring resilience and sustainability for future generations.”

Harvest & Vinification

I asked Van Beek to run through the sorting process upon entering the winery at Giscours.

“A very drastic hand-picking in small crates is done sequentially, with plots harvested in multiple passes to separate young and old vines in order to ensure precision and optimal ripeness. We proceed to a manual sorting of the whole grapes on vibrating tables followed by a delicate destemming using a slight oscillating movement to keep the berries in perfect condition as they are fully separated from the stalks. These berries go through density-sorting using a water-based flotation system, which removes impurities, pieces of stalks, vegetal material and all berries that do not correspond to our quality standard. We aim for gentle extraction, including a one-week pre-fermentation cold maceration for the Merlots, eschewing the use of sulfur at vatting, using non-Saccharomyces yeast [Torulaspora delbrueckii] to limit microbial deviations, gentle maceration without aeration, and long and slow extraction. We manage the oxygen precisely.”

The historical vat room has been equipped with vats of various sized, between 20- and 200 hectolitres. “This allows us a more subtle division and separation of the different soils of Giscours,” Van Beek explained. “The grapes are lightly crushed and put into the vats by gravity. The vat room has used gravity from its inception in the 19th century. We work with ten different coopers, exclusively using selected fine-grained oak from central France. We only use 40-50% new oak each year. The wines spend 14 months in these barrels according to the different soils, terroirs and grape varieties. We carry out an egg-white fining at very low doses, and a light filtration is done before the bottling. [Consultant] Thomas Duclos joined us in 2019, though he did the blending in 2018. We work much more reductively nowadays.”

The Wines

The small group consisting of members of the winemaking team, including Van Beek, Technical Director Didier Foret, Technical Manager Jérôme Poisson, plus a few French journalists, gathered at the estate last October for this vertical tasting. Van Beek chose the vintages, electing not to repeat those that I tasted at a previous vertical tasting held in 2015.

We broach the wines in chronological order, commencing with the 1938 Giscours, a vintage that I have only seen a couple of times before. It puts in a creditable performance, yes, a little rustic and missing a bit of ripeness, but fresh and respectable for its age. The 1957 Giscours, the only vintage served blind at the following dinner, was the real surprise, an exquisite mature Margaux that has far more ripeness than you would expect from what was a mediocre season. There’s joie-de-vivre from start to finish. Une bonne surprise! The 1963 Giscours is from one of the worst growing seasons in a difficult decade, and it was surely heavily chaptalised by Tari at the time. As someone who roots for the underdog, I wanted to like it, but it is scrawny, dry and loaded with VA. The 1964 Giscours comes from a vintage when the Médoc suffered late-harvest rain and is therefore superior on the earlier-picked Right Bank. The 1964 attested to the fact that it’s from a modest vintage, a sweet-‘n-sour Giscours that was actually above my low expectations. But these were halcyon days for Giscours with high points such as the 1961, 1966 and 1970 (not tasted here, but you will find reviews in the database). The 1967 Giscours was an absolute joy, showing a bit of VA and quite Pinot-like, yet full of zest and fine tannins. This is a vintage that frequently surpasses its lowly reputation, overshadowed by 1966 and 1970. Likewise, the 1971 Giscours bucked the trend for 1971 also being a Right Bank vintage, rustic and garrigue-like but with impressive backbone. Best of all, the wonderful 1975 Giscours—the most impressive in terms of aromatics, with filigree tannins and just a slight dryness on the finish where many of its peers now taste astringent.

After these, the Merlot-dominated vineyard engendered some decent, if unexciting, wines. The 1982 Giscours ought to have been better, but to be honest, the 1985 Giscours and 1989 Giscours punch above expectations. The estate “bumped along” in the latter half of the nineties as the vineyard underwent the large-scale replanting program, though amongst these, the 1998 Giscours has the best balance and agreeable spiciness towards the finish. It is the 2001 Giscours rather than the 2000 that indicates the reconfiguration of varieties was beginning to have a positive effect. Today, the 2001 is drinking beautifully, very pliant, with a dash of white pepper on the finish.

Henceforth, we tasted every vintage. The highlights included an excellent 2005 Giscours and 2009 Giscours, which unusually, I preferred to the 2010 that misses some elegance and feels a bit laboured on the finish. But do not ignore a quite delicious 2011 Giscours with its Pauillac-like pencil lead finish, a wine that transcends the limitations of the growing season. The 2015 and 2016 Giscours represent back-to-back successes that now approach their drinking windows, but perhaps the 2017 is the hidden gem from that period. The finest vintage in recent years is the 2022 Giscours with its satin-textured tannins and mineral-driven finish that just pips the spicier but still outstanding 2020.

Final

Thoughts

So, there we have Giscours. Flick through the history pages and the château has not had the easiest of rides, flirting with extinction, court cases, tragic accidents and reconstituting the large vineyard from the mid-nineties that, until new re-plantings reached maturity, knocked it off track.

But they pulled through. It’s a property that rolled up its sleeves and addressed the issues. The results can be tasted in recent vintages. Perhaps Giscours has never quite earned the kudos of its peers, partly due to distracting shenanigans in the background, but maybe because it enjoys a large production and the wines rarely attract investors (not that this should be the priority of any self-respecting wine, quite the opposite). To get to where Giscours is nowadays, it needed a captain at the helm, a steadying force to guide it through the last three decades. That person was obviously Alexander Van Beek. Recent vintages rank amongst some of the best the estate has ever produced, though I maintain, perhaps to his chagrin, that Giscours can take another step up in quality and consistently challenge the top guns of the appellation.

Hey, I’m a wine critic. We never get it wrong…do we?

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Intellect & Senses: Bordeaux With Time, Neal Martin, March 2025

A Place Beyond Praise: Bordeaux 2022, Neal Martin, February 2025

Bordeaux 2020 – The Southwold Tasting, Neal Martin, November 2024

The Misunderstood Margaux: Marquis de Terme 1947-2021, Neal Martin, October 2024

Written in the Stars: Bordeaux 1865-2020, Neal Martin, December 2023

Book Excerpt: The Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide One Hundred and Fifty Years from 1870-2020, Neal Martin, April 2023