Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

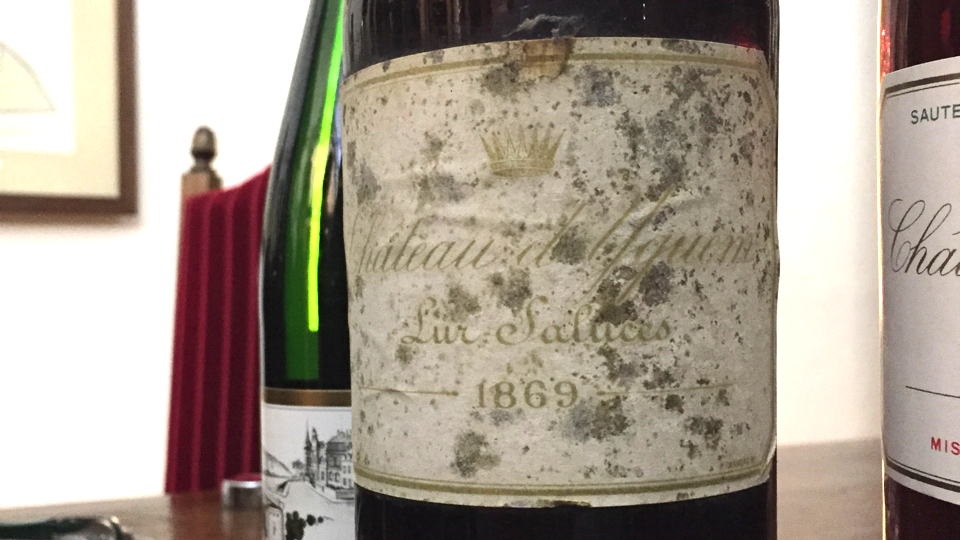

1869, 1879 & 1893 d’Yquem

BY NEAL MARTIN | MARCH 04, 2019

I would never claim to be an expert blind taster – far from it – though I do have my moments. One transpired in January at Hide restaurant, where two vintages of d’Yquem were served blind as a fitting finale to an epic Pétrus dinner. Guests were invited to name the vintage. “It is definitely very old but certainly a great Sauternes vintage,” I piped up, in my finest Michael Broadbent impersonation. “I think it is the… [cue drumroll] …1893.” Bingo. Cue a susurrus of “How did he do that?” Of course, it is always preferable for moments of tasting prowess to coincide with an audience. I acted nonchalant whilst inside I basked in the glow and completed my victory lap. (More often in these situations I make a complete fool of myself.) The other bottle was the 1967 d’Yquem, but instead of reporting on that now, I decided to present my three encounters with 19th-century d’Yquem.

Historical context is important. These were all born in Sauternes’s halcyon days, when d’Yquem was esteemed as its pinnacle, with prices to match, outstripping even Lafite-Rothschild. Sweetness, pertaining not just to wine but to all kinds of gastronomy, signified luxury and wealth. D’Yquem was ne plus ultra. Its aura was enhanced in 1859 when the brother of the Tsar of Russia, the Grand Duke Constantine, forked out an astronomical 20,000 gold francs for a barrel of the 1847. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, d’Yquem reigned imperiously. It was not until the 1930s that tastes began shifting away from sweet wines to dry reds, though d’Yquem will never relinquish its status as Bordeaux’s best sweet wine, a reputation consecrated by the 1855 classification as its sole Premier Cru Supérieur.

These three bottles were all poured blind on separate occasions. The tasting note for the 1879 d’Yquem attests that being extremely old, rare and valuable does not exempt it from criticism. Two others, the 1869 and 1893, evidence exactly why there is something magical about d’Yquem. Both come from long-forgotten but great vintages. They transfixed their respective audiences decades later, even before their ages were revealed. I broach them chronologically.

The 1869 d’Yquem remains the oldest vintage I have tasted. It was an additional bottle generously donated to finish a remarkable dinner in Beaune. Picked on September 5, according to Michael Broadbent (who I presume did not witness it first-hand), it has a noticeably deep colour with a light flor-like scent on the nose, yet there is patently no sign of any oxidation, just bewitching scents of crème brûlée and ripe fig, and later, syrup. It is vivid and entrancing, with wonderful definition. The slightly viscous palate is exquisitely balanced and harmonious, not to mention one of the most exotic I have encountered in an ancient d’Yquem, offering pure fig and date notes and, peculiarly, sporting traces of red fruit and a hint of elderflower on the finish. Sensational in every way – it’s as simple as that. Tasted blind in Beaune at the 1243 Club. 99/Drink: 2019-2040. This bottle of 1879 d’Yquem had been re-corked at the château in 1993. It has a delicate but not frail bouquet of dried honey, almond, beeswax, mulch and chlorophyll aromas – all very attractive though not mind-blowing. The palate is medium-bodied, mellow and refined, showing good acidity and delivering dried honey, wax, dried orange peel and mandarin towards the finish, which just fades gracefully away, as you might forgive a 134-year-old Sauternes. This is a piece of history that continues to emit pleasure like a distant twinkling star. Tasted blind at a private dinner in Zurich. 90/Drink: 2019-2025.

This is the actual bottle of 1893 as depicted by

the auction house where it was acquired. Apparently one of the sommeliers

scarpered with the label after it fell off in the restaurant.

Cognoscenti cite 1811 and 1847 as the most famous d’Yquems of that century; however, the 1893 d’Yquem stands beside them. It is an extraordinary wine born in a notoriously hot summer that favored Sauternes over the reds. Figures gleaned from Yquem’s official website make you rub your eyes in disbelief. Unsurprisingly, the growth cycle was one month ahead of normal and the harvest commenced on August 28, finishing on September 15 after three tries through the vineyard. Despite this unprecedented early picking, potential alcohol averaged 22°, some lots approaching 30°. Yields were a bountiful 25hl/ha, which equated to 75 barrels, full capacity for the cellar at that time. At 126 years old, this elixir effortlessly shrugs off its age. Iridescent amber in color, it has a beguiling bouquet of dried honey, rosehip, stewed peaches and just a suggestion of Tokaji Azsù. The delineation is enthralling and difficult to reconcile with such a hot growing season. The palate is blessed with exquisite balance and an electric wire of acidity that slices through what must once have been very intensely botrytized fruit. This is still viscous and caressing, offering caramelized oranges, honeycomb and just a hint of yellow plum towards the ineffably complex finish. Maybe because of its venerable age, the 1893 does not quite possess the persistence of the very greatest d’Yquems that I have tasted, but it remains a truly fabulous Sauternes from a remarkable growing season. Tasted blind at the end of the Pétrus dinner at Hide in London. 99/Drink: 2019-2040.

- 2026

- Remembering Daniel Cathiard (Feb 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour 2026 New Releases (Feb 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 1961 & 2019 Smith Haut Lafitte (Feb 2026)

- Bordeaux 2023 in Bottle: Coming Around Again (Feb 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Hanzell Vineyards Pinot Noir & Chardonnay (Feb 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Le Dôme (Feb 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 2013 Domaine Didier Dagueneau – Louis Benjamin Pouilly-Fumé Silex (Jan 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 1962 La Gaffelière (Jan 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 2020 Champagne Nakada-Park Brut Nature Vignes de Gyé-Sur-Seine (Jan 2026)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis Montée de Tonnerre 1er Cru (Jan 2026)

- 2025

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Mouton-Rothschild (Dec 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1955 Domaine Georges Roumier Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses 1er Cru (Dec 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Petrus (Dec 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Montrachet Grand Cru (Dec 2025)

- Battle Royale! Bordeaux 1961, 1982, 1990 & 1995 (Dec 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Champagne Louis Roederer – Inflection Points (Dec 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1967 Certan de May (Nov 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1945 Riccardo Viganò Barolo Gran Riserva Cannubi (Nov 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2013 Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury Le Corton Grand Cru (Nov 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Lagrange (Saint-Julien) (Oct 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Grand Mayne (Oct 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 Trotanoy (Oct 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Domaine Mathilde et Yves Gangloff Côte-Rôtie La Barbarine (Oct 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1964 Maison Léon Revol Côte-Rôtie (Sep 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine J.L. Chave 1991 L’Hermitage & 1995 Ermitage Cuvée Cathelin (Sep 2025)

- Hand Over the Keys: Brane-Cantenac 1928-2023 (Sep 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2016 Storm Wines Pinot Noir Vrede (Sep 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Domaine Leflaive Chevalier-Montrachet Grand Cru (Sep 2025)

- A Woman’s Touch: Lafleur 1985-2022 (Sep 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Calon-Ségur (Sep 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2025 Aramasa No. 6 A-Type Junmai Daiginjo Sake (Aug 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1924, 1929 & 1955 Meyney (Aug 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 Joh. Jos. Prüm Riesling Wehlener Sonnenuhr Auslese (Aug 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Laurent Perrier Grand Siècle Lumière du Millénaire (Aug 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Penfolds Chardonnay Yattarna (Jul 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Maximin Grünhaus – von Schubert Riesling Abtsberg Auslese Nr. 57 (Jul 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Castell’in Villa Library Releases (Jul 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Guy de Barjac Cornas (Jul 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1952 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Romanée-Conti Grand Cru (Jun 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Noël Verset Cornas (Jun 2025)

- A Century of...Fives (Jun 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Hennebelle (Jun 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2021 Château Simone Palette Blanc (Jun 2025)

- Bordeaux: The Crisis Laid Bare (Jun 2025)

- Bordeaux 2015 At Age Ten (Jun 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Dom Ruinart Brut Rosé (Jun 2025)

- The Innings Continues: 1948 to 1995 Yquem (May 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1977 Diamond Creek Vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon Volcanic Hill (May 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Pierre-Yves Colin-Morey Montrachet Grand Cru (May 2025)

- Going Underground: Clos Fourtet 1989-2019 (May 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2022 António Madeira Branco Vinhas Velhas (May 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Domaine Tempier Bandol Cuvée Classique (May 2025)

- Event Horizon: Bordeaux 2024 Primeur (May 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Marcel Lapierre Morgon Cuvée Marcel Lapierre (Apr 2025)

- 2024 Bordeaux En Primeur: The Razor’s Edge (Apr 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Veuve Clicquot Vintage Rosé (Apr 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Vilmart Coeur de Cuvée 2006 & 2003 (Apr 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: A Landmark Vintage – Henschke 2021 (Apr 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1948 La Tour Blanche (Mar 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Ridge Monte Bello (Mar 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Niepoort Charme Tinto Douro (Mar 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2022 Yquem (Mar 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Ioppa Ghemme 1970-1975 (Mar 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Domaine Hubert Lignier Clos de la Roche Grand Cru (Feb 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour 2025 Late Releases (Feb 2025)

- A Place Beyond Praise: Bordeaux 2022 (Feb 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Breaking the Rules – La Chapelle Grange (Feb 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 & 2010 Cos d’Estournel (Feb 2025)

- 2022 Bordeaux in Bottle: Living in the Present (Jan 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Domaine Dureuil-Janthial Rully En Guesnes Wadana (Jan 2025)

- Vinous Table: Le Lion d’Or, Arcins, France (Jan 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour 2025 New Releases (Jan 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Philip Togni Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon (Jan 2025)

- Cellar Favorite: 2016 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis Valmur Grand Cru (Jan 2025)

- Vinous Table: Maison François, London, UK (Jan 2025)

- 2024

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo Brunate (Dec 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Domaine Pierre Morey Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru (Dec 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1808 Braheem Kassab “SS” Sercial Madeira (Dec 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: Vintage Port in Excelsis 1924-1950 (Dec 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Domaine Leroy Nuits Saint-Georges Aux Boudots 1er Cru (Dec 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1921 Yquem (Nov 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 & 2001 Haut-Bages Libéral (Nov 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Bruno Giacosa Barbaresco Riserva Asili (Nov 2024)

- Bordeaux 2020 – The Southwold Tasting (Nov 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1945 Troplong Mondot (Nov 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1973 Californian Cabernets (Oct 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Henschke Lenswood Abbotts Prayer Vineyard (Oct 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1924 Gruaud Larose (Oct 2024)

- The Misunderstood Margaux: Marquis de Terme 1947-2021 (Oct 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: Castello dei Rampolla: Library Releases (Oct 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1984 Ridge Zinfandel Geyserville Trentadue (Sep 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Cheval Blanc (Sep 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Kanonkop Paul Sauer (Sep 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Romanée-Conti Grand Cru (Sep 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Lisini Prefillossero (Aug 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1961 & 2012 Mouton-Rothschild (Aug 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Rustenberg Peter Barlow (Aug 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1928-1998 Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande (Aug 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 and 1959 Pape Clément (Aug 2024)

- Memories Elide: Vieux Château Certan 1923-2020 (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2022 Kei Shiogai Bourgogne Blanc (Jul 2024)

- The Minnow: Sigalas Rabaud 1975-2019 (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Domaine J.L. Chave L’Hermitage Blanc (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Envínate Lousas Parcela Camiño Novo (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Latour & 1971 Les Forts de Latour (Jul 2024)

- Rockeries in Living Rooms: 1988 vs. 1989 Bordeaux (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru and 1989 Meursault Les Perrières 1er Cru (Jul 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Pontet-Canet (Jun 2024)

- Desert Island Dinner: 1961 Pomerol in Excelsis (Jun 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 Araujo Estate Wines Cabernet Sauvignon Eisele Vineyard (Jun 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1924 Bouchard Père & Fils Chassagne-Montrachet Rouge (June 2024)

- A Century of…Fours (Jun 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Robert Mondavi Winery Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve (Jun 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Château Gilette Doux (May 2024)

- The Bordeaux Soundtrack: Icons at Legacy Records (May 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: Castello di Ama - Looking Back at the 2006s (May 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1994 Penfolds Grange and 1975 Bin 95 Grange Hermitage (May 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1930 KWV Muscadel Bin 14 Late Bottled Vintage (May 2024)

- Bordeaux at the Crossroads: 2023 En Primeur (April 2024)

- The Dalmatian Vintage: Bordeaux 2023 (Apr 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1938 Paul Jaboulet Aîné Côte-Rôtie (Apr 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2016 Domaine de la Grange des Pères Vin de Pays de L'Herault (Apr 2024)

- Past Becomes Now: Lafite-Rothschild 1874-1982 (Apr 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1993 Domaine de Chevalier (Apr 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Latour à Pomerol (Apr 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 M & C Lapierre Morgon Marcel Lapierre Cuvée MMXIV (Apr 2024)

- An Exploration of Time: Gruaud Larose 1831-2018 (Mar 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Domaine Samuel Billaud Chablis Mont de Milieu 1er Cru (Mar 2024)

- Test of Endurance: Bordeaux 2014 Ten Years On (Mar 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 René Balthazar Cornas (Mar 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Staatsweingut Eltville Rauenthaler Langenstück Riesling Spätlese (Mar 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1948 Coufran (Mar 2024)

- 2021 Bordeaux: L’Enfant Terrible (Feb 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1973 La Fleur-Pétrus (Feb 2024)

- 2+2=5: Bordeaux 2021 In Bottle (Feb 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: 2024 New Releases (Feb 2024)

- Come On Aline: Château Coutet 1943-2017 (Feb 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Pol Roger Brut Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill (Feb 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2020 Domaine Bernard-Bonin Meursault La Rencontre (Feb 2024)

- Survive Us All: Latour 1858-2018 (Feb 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1981 & 1992 Le Pin (Jan 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 & 1967 Domaine J.L. Chave L’Hermitage (Jan 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Ridge Vineyards Zinfandel Canyon Road & 1985 Monte Bello (Jan 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 1969 Bodegas Vega Sicilia Unico (Jan 2024)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Château Canon (Jan 2024)

- 2023

- The Quiet One: 1962 Burgundy & Bordeaux (Dec 2023)

- Written in the Stars: Bordeaux 1865-2020 (Dec 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1899, 1947 & 1970 Yquem (Dec 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Domaine des Miroirs (Kenjiro Kagami) Vin de France Entre Deux Bleus (Dec 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1974 Beaulieu Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon Private Reserve Georges de Latour (Dec 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2016 Domaine J-F Mugnier Musigny Vieilles Vignes (Dec 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Hospices des Moulin-à-Vent Moulin-à-Vent (Nov 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Maximin Grünhaus – von Schubert Abtsberg Riesling Auslese #93 (Nov 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Henschke Cabernet Sauvignon/Shiraz (Nov 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1890, 1990, 2005 & 2015 Branaire-Ducru (Nov 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Beau Paysage Tsugane La Montagne (Oct 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Beaux Frères Pinot Noir The Beaux Frères Vineyard (Oct 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 E. Pira & Figli Barolo (Oct 2023)

- Poetic License: Siran 1920-1929 (Oct 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1981 Petrus (Oct 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2003 Philip Togni Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon Estate (Oct 2023)

- Margaux Focus 3: Château Margaux (Sep 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Domaine Jean-Marc Pillot Chassagne-Montrachet Les Vergers 1er Cru (Sep 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Domaine d'Auvenay Bourgogne Aligoté Sous Chatelet (Sep 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Boekenhoutskloof Syrah (Sep 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2016 Royal Tokaji Essencia (Aug 2023)

- Margaux Focus 2: Château Palmer (Aug 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: San Giusto a Rentennano Chianti Classico: 2001-1990 (Aug 2023)

- Margaux Focus 1: Château Durfort-Vivens (Aug 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine Jean-Marie Guffens Mature Pouilly-Fuissé (Aug 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Chartreuse Yellow Label - Distilled 1935 (Aug 2023)

- A Century of Bordeaux: The Threes (Aug 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1865 Giscours (Aug 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira - 2023 Bottlings (Jul 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Famille Hugel - The 2015 Riesling Séléctions de Grains Nobles S and 2014 Riesling Grossi Laüe (Jul 2023)

- Passing the Baton: Lynch-Bages 1945-2018 (Jul 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Doisy-Védrines (Jul 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Domaine Cheysson Chiroubles (Jul 2023)

- Going Back to My Roots: Putting Liber Pater In Context (Jun 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Seven for Seven – A Brief Tour of Napa Valley (Jul 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004, 2006 & 2009 Boekenhoutskloof Semillon (Jun 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2020 Château d’Yquem (Jun 2023)

- Moving On: Lafon-Rochet 1955-2017 (Jun 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2013 Screaming Eagle (Jun 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Dom Pérignon Rosé (Jun 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Domaine Y. Clerget Meursault Les Chevalières (May 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Vilmart & Cie Brut Coeur de Cuvée (May 2023)

- You’re Unbelievable: Bordeaux 2022 (May 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Taylor’s Very Very Old Tawny Port (Coronation of King Charles III Limited Bottling) (May 2023)

- 2022 Bordeaux En Primeur: Balance Imbalance (May 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Wendouree Cabernet Sauvignon (May 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Marc Brédif Vouvray Grande Année (May 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2003 Te Mata Estate Coleraine (Apr 2023)

- Book Excerpt: The Complete Bordeaux Vintage Guide 1870-2020 (Apr 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1945 Domaine Henri Lamarche Vosne-Romanée Les Suchots 1er Cru (Apr 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Torres Gran Coronas Reserva (Apr 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1960, 1974 and New Releases of Château Musar (Apr 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Ao Yun (Mar 2023)

- Lower Your Sails (Or Breeches): Beychevelle 1929-2019 (Mar 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Penfolds Shiraz Kalimna Bin 28 (Mar 2023)

- Not Classed, but Classy: Haut-Bergeron 1961-2019 (Mar 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Niepoort Batuta and Redoma (Mar 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: 2023 Releases (Mar 2023)

- Bordeaux 2019: The Southwold Tasting (Feb 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: Two from Mayacamas (Feb 2023)

- Bordeaux 2020: Saving the Best for Last (Feb 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1923 Seppeltsfield Para Vintage Tawny (Feb 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Philip Togni Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon Estate (Feb 2023)

- Thrice Is Nice: Bordeaux 2020 in Bottle (Feb 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Pape Clément (Feb 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1895 Cossart Gordon Bual (Jan 2023)

- Cleaning Out the Cupboard: Bordeaux 1943-2020 (Jan 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Domaine de Trévallon Coteaux d’Aix-en-Provence Les Baux (Jan 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 1974 Diamond Creek Vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon Gravelly Meadow (Jan 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Weingut Keller Dalsheimer Hubacker Riesling Auslese *** Goldkapsel (Jan 2023)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis 1er Cru Forêt (Jan 2023)

- 2022

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 & 2004 Dom Pérignon (Dec 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury Meursault Les Rougeots (Dec 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1943 Petrus (Nov 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1993 Domaine Jean Grivot Nuits Saint-Georges Les Roncières (Nov 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Domaine Robert Denogent Pouilly-Fuissé Les Carrons Vieilles Vignes (Nov 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 Dominus (Nov 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1928-2011 Lascombes (Oct 2022)

- Bending Rules: Les Carmes Haut-Brion 1955-2019 (Oct 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1964 La Tour Figeac (Oct 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Domaine Georges Vernay Condrieu (Oct 2022)

- Dive In: Cantenac Brown 1978-2018 (Oct 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Etienne Guigal Côte-Rôtie La Mouline (Oct 2022)

- Looking Back: 2007 Sauternes (Oct 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Domaine Alain Voge Cornas (Oct2022)

- A Century of Bordeaux: The Twos (Sep 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira – 2022 Bottlings (Sep 2022)

- Léoville-Poyferré 1936-2018 (Sep 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2018 Quilceda Creek Cabernet Sauvignon (Sep 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 & 2009 Kanonkop Paul Sauer (Sep 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 & 2011 Porseleinberg (Sep 2022)

- Memories Tumble Out: Pichon Baron 1937-1990 (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1940 Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1920 Clarets (Aug 2022)

- Magic and Madness: Climens 1912-2020 (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Royal Tokaji Company Tokaji Essencia (Aug 2022)

- Bring Out Your “Dead”: Pichon-Lalande 1957-2013 (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Lune d’Or 2012-2020 (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Raiding the Cellar at Inspire Napa Valley (Aug 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Klein Constantia Vin de Constance 1991-2019 (Jul 2022)

- Where the Heart Is: Ducru-Beaucaillou 1934-2018 (Jul 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Domaine Henri Germain & Fils Meursault Charmes 1er Cru (Jul 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: San Giusto a Rentennano Chianti Classico 2002-2010 (Jul 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Domaine Jean-Paul & Benoît Droin Chablis Les Clos Grand Cru (Jul 2022)

- Bols Blue to Bordeaux: Barde-Haut, Clos l’Église & Poesia (Jun 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Domaine Denis Mortet Bonnes-Mares Grand Cru (Jun 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1981 Wynns Coonawarra Estate Hermitage (Jun 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Pavie (Jun 2022)

- Fronsac Royalty: Château de La Dauphine 2001-2018 (Jun 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971, 2001 & 2011 Château de Beauregard Pouilly-Fuissé Vers Cras (Jun 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2018 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Vosne-Romanée Les Petits Monts 1er Cru (May 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2018 Taaibosch Crescendo (May 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1946 Figeac (May 2022)

- Enticingly Fallible: Bordeaux 2021 En Primeur (May 2022)

- 2021 Bordeaux En Primeur: Back to Classicism (May 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Clos Rougeard Saumur Blanc Brézé (May 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Roagna Barbaresco Pajè (May 2022)

- This Is Not Just Another Winery: Haut-Bailly 1964-2018 (Apr 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Louis Latour Pommard Les Epenots 1er Cru (Apr 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 & 1990 Clinet (Apr 2022)

- Unrivalled/ Unequalled: Yquem 1921–2019 (Apr 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2020 Clos de Vougeot Cuvée de l’Abbaye de Citeaux (Apr 2022)

- The Comedown: Bordeaux 2011 Ten-Years-On (Apr 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1921 Siran (Apr 2022)

- The Wines That Shaped My Life (Mar 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Hamilton Russell Vineyards Pinot Noir 1981-2021 (Mar 2022)

- Pages in the Photo Album: Vieux Château Certan 1928-2013 (Mar 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Tyrrell's Wines Semillon Vat 1 Hunter Valley (Mar 2022)

- Château Latour: 2022 New Releases - Neal Martin (Mar 2022)

- The Judgement of Clapham Junction (Mar 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Bollinger: 2022 New Releases (Mar 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Grand-Puy-Lacoste (Feb 2022)

- 2019 Bordeaux from Bottle: The Two Towers (Feb 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Matthieu Barret Cornas Billes Noires (Feb 2022)

- Branas Grand Poujeaux 2002-2019 (Feb 2022)

- Omne Trium Perfectum: Bordeaux 2019s in Bottle (Feb 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1967 Climens (Feb 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Taylor’s Single Harvest Port (Feb 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: 2022 New Releases (Jan 2022)

- Pierre, Denis & Jean-Jacques: Doisy-Daëne & L’Extravagance 1942-2013 (Jan 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1952 Latour (Réserve des Proprietaires) (Jan 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Bruno Giacosa Barbaresco Santo Stefano di Neive (Jan 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Domaine Macle Château-Chalon (Jan 2022)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Marcel Lapierre Morgon Cuvée Marcel Lapierre (Jan 2022)

- 2021

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Kunin Syrah Alisos Vineyards (Dec 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: Vins Doux Naturel 1961-1991 (Dec 2021)

- A Janus with Soul: Figeac 1943–2016 (Dec 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1984 Château Margaux (Dec 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo (Nov 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Gaja Barbaresco (Nov 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Pian dell'Orino Rosso di Montalcino (Nov 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Haut-Brion (Nov 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Malartic-Lagravière (Nov 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1977 Chateau St. Jean Cabernet Sauvignon Glen Ellen Vineyards (Oct 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1964, 1971 and 1974 Domaine Couly-Dutheil Chinon (Oct 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1969 Castello di Monsanto Chianti Classico Riserva Il Poggio (Oct 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaines Delon: Recent Cellar Releases (Oct 2021)

- Stand and Deliver: 2001 Sauternes (Sep 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Château de Beaucastel Châteauneuf-du-Pape (Sep 2021)

- Looking Backward/Looking Forward: 2000 vs 2001 Bordeaux (Sep 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Armando Parusso Barolo Bussia (Sep 2021)

- Mission Complete: La Mission Haut-Brion 1928–2011 (Sep 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 Domaine Charles Joguet Chinon Clos de la Dioterie (Sep 2021)

- Left Bank on the Right: Jean Faure 2007–2018 (Sep 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: Quinta do Noval 2019s (Sep 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 François Cotat Sancerre Les Culs de Beaujeu (Aug 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Léoville Las-Cases (Aug 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Tenuta delle Terre Nere Etna Rosso Feudo di Mezzo Il Quadro delle Rose (Aug 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Galardi Terra di Lavoro Roccamonfina Rosso (Aug 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Domaine Bonneau du Martray Corton Grand Cru (Aug 2021)

- So Chic, So Listrac: Fourcas Hosten (Jul 2021)

- Two + Two = Trouble (Jul 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Domaine Laroche Chablis Les Blanchots La Réserve de l’Obédiencerie Grand Cru (Jul 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2003 Larrivaux (Jul 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Domaine de Pallus Chinon (Jul 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Domaine Jean-Marc Burgaud Morgon Côte du Py (Jul 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Lynch-Moussas (Jun 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2018 Hospices de Beaune Beaune 1er Cru Cuvée Dames Hospitalières (Jun 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Domaine Georges Roumier Morey-Saint-Denis Clos de la Bussière 1er Cru (Jun 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1896 Taylor’s Single Harvest Port (Jun 2021)

- 2020 Bordeaux En Primeur: Almost Back to Normal (Jun 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Château de Pommard Pommard (Jun 2021)

- Vingt-Vingt Vins: Bordeaux 2020 (May 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Vietti Barolo Castiglione (May 2021)

- His Father’s Son: Grand Mayne 1955-2011 (May 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Soldera Sangiovese (May 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Mvemve Raats MR de Compostella (May 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Cupano Brunello di Montalcino (Apr 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Poggio Il Castellare Brunello di Montalcino (Apr 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2018 Louis Jadot Beaune 1er Cru Célébration (Apr 2021)

- 2005 Bordeaux: Here and Now (Apr 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1980 Domaine Hudelot-Nöellat Vosne-Romanée Les Petits-Monts 1er Cru (Apr 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Tenuta delle Terre Nere Etna Bianco Santo Spirito Cuvée delle Vigne Niche (Apr 2021)

- Bordeaux 2018: Not Back in Black (Mar 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: The Fives at Château d’Issan (Mar 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: 2021 New Releases (Mar 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Minimalist Wines Stars In The Dark (Mar 2021)

- The Future’s Definitely Not What It Was: Bordeaux 2018 (Mar 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Quintarelli Amarone della Valpolicella Classico (Mar 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Domaine Armand Rousseau Chambertin Grand Cru (Feb 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Saintsbury Pinot Noir Brown Ranch (magnum) (Feb 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Domaine Roumier Morey-Saint-Denis Clos de la Bussière & Chambolle-Musigny Les Cras (Feb 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1928 Calon-Ségur (Feb 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Castello di Monsanto Chianti Classico Riserva Il Poggio (Feb 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Domaine Hubert Lamy Saint-Aubin En Remilly 1er Cru (Jan 2021)

- Choose Wisely: Château Sérilhan 2008–2017 (Jan 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1967 Château d’Yquem Sauternes Premier Grand Cru (Jan 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 1961 Taylor’s Very Old Single Harvest Port (Jan 2021)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis Blanchot Grand Cru (Jan 2021)

- 2020

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Marcassin Pinot Noir Sonoma Coast (Dec 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Mastroberardino Taurasi Radici Riserva (Dec 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2019 Paulus Wine Co. Chenin Blanc Bosberaad (Dec 2020)

- Lagrange 1959-2015 (Dec 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Vietti Barbera d'Asti La Crena (Dec 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Domaine Yvon Clerget Clos Vougeot Grand Cru (Nov 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Domaine Didier Montchovet Bourgogne Hautes-Côtes de Beaune (Nov 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Dunn Vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley (Nov 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Domaine des Comtes-Lafon Meursault Clos de la Barre (Nov 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Monsanto Chianti Classico Riserva (Nov 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 Dow’s Vintage Port (Oct 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Château de Beaucastel Châteauneuf-du-Pape Hommage à Jacques Perrin Grande Cuvée (Oct 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1955 Maison Leroy La Romanée Grand Cru (Oct 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Tiberio Montepulciano d’Abruzzo Colle Vota (Oct 2020)

- Saturday Morning: Larcis Ducasse 1945-2017 (Oct 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1919 Montrose (Sep 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1964 Krug Private Cuvée & 1979 Collection (Sep 2020)

- 2018 Château d'Yquem (Sep 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 & 1989 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Riserva Collina Rionda (Sep 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s New Releases (Sep 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Domaine des Comtes Lafon Meursault Perrières 1er Cru (Aug 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Trimbach Clos Ste. Hune Hors Choix Vendanges Tardives (Aug 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1899 Marqués de Murrieta Rioja Blanco (Aug 2020)

- Southwold: 2016 Bordeaux Blind (Aug 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2015 Jean-François Ganevat Côtes de Jura Les Chalasses Vieilles Vignes (Aug 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Château de Pibarnon Bandol (Jul 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: Soldera: A Look at the 2013 & 2014 (Jul 2020)

- The Most and Least Important of Things: Petrus 1897–2011 (Jul 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Weingut Dr. von Basserman-Jordan Forster Jesuitengarten Riesling TBA (Jul 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Fritz Haag Brauneberger Juffer-Sonnenuhr Riesling Auslese #9 (Jul 2020)

- Delivering Where It Counts: Meyney 1971–2017 (Jul 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: NV Mullineux Olerasay 2° (Jul 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Haut-Bailly (Jun 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Le Pin (Jun 2020)

- 2019 Bordeaux: A Long, Strange Trip (Jun, 2020)

- Uncertain Smile: Bordeaux 2019 (Jun 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Col d’Orcia Brunello di Montalcino (Jun 2020)

- Château Siran 1918-2008 (Jun 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Taylor’s Single Harvest Port (Jun 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Château Trotanoy (Jun 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Robert Ampeau et Fils Volnay Santenots 1er Cru (May 2020)

- Hopes and Dreams: Canon Chaigneau 1998-2019 (May 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1957 Penfolds St. Henri Claret (May 2020)

- Six Decades of Pavie-Macquin: 1928-2018 (May 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Guastaferro Taurasi Primum (May 2020)

- Remember, Remember: 1945 Bordeaux (May 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Domaine Christophe Roumier Vosne-Romanée Les Beaumonts 1er Cru (May 2020)

- No Relation: Clos Saint-Martin 1964-2017 (Apr 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Carlisle Syrah Cardiac Hill Bennett Valley (Apr 2020)

- Squares & Circles: Bordeaux ‘10 At Ten (Apr 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Podere La Vigna Brunello di Montalcino (Apr 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2013 Naudé Old Vines Chenin Blanc (Apr 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Château Latour (Apr 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1931 d’Yquem (Mar 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1937 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche Grand Cru (Mar 2020)

- In Good Taste: Branaire-Ducru 1928-2013 (Mar 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1933 Domaine René Engel Grands-Echézeaux Grand Cru (Mar 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2017 Hatzidakis Winery Cuvée No. 15 Assyrtiko (Mar 2020)

- 2017 Bordeaux – Mirror, Mirror on The Wall… (Mar 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Pepe Raventós Mas del Serral (Mar 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Soldera – Case Basse Brunello di Montalcino (Feb 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1959 Marqués de Murrieta Castillo Ygay Gran Reserva Especial Rioja (Feb 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1949 Château Figeac (Feb 2020)

- Vintage Seeks Home: Bordeaux 2017 In Bottle (Jan 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1945 Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé Musigny Vieilles Vignes Grand Cru (Feb 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1924 Château Filhot (Jan 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1957 Domaine Ramonet Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru (Jan 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Domaine Taupenot-Merme Clos des Lambrays Grand Cru (Jan 2020)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 Dow’s Vintage Port (Jan 2020)

- 2019

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 & 1990 Château de Beaucastel Châteauneuf-du-Pape (Dec 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1939 & 1950 Cheval Blanc (Dec 2019)

- Cellar Journal: Bordeaux 1920-2015 (Dec 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2013 Domaine J-F Mugnier Musigny Vieilles Vignes Grand Cru (Dec 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1968 Cappellano Barolo (Nov 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 La Tour Haut-Brion (Nov 2019)

- The Future’s Not What It Was: Bordeaux 2018 (Nov 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1994 Domaine Ponsot Morey-Saint-Denis Clos des Monts Luisants Blanc 1er Cru (Nov 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Château Latour (Nov 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1994 Kanonkop Wine Estate Paul Sauer (Oct 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1975 Egon Müller Riesling Scharzhofberger Trockenbeerenauslese (Oct 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Domaine Robert Arnoux Vosne-Romanée Les Suchots 1er Cru (Oct 2019)

- A Century - Not Out: Talbot 1919-2010 (Oct 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: Marqués de Riscal Gran Reserva 1952-2015 (Oct 2019)

- Remembering Jean-Bernard Delmas (Oct 2019)

- The Cat’s Whiskers: Bordeaux 1961 (Oct 2019)

- Cellar Favorites: 1970 Giacomo Conterno Barolo & Barolo Riserva Monfortino (Sep 2019)

- The Other Side of Bordeaux (Sep 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Dunn Cabernet Sauvignon Howell Mountain (Sep 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Carbonnieux Blanc (Sep 2019)

- A Century of Bordeaux: The Nines (Sep 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Le Macchiole Paleo Rosso (Sep 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: MCDXIX, The Winemaker’s Selection Madeira – Blandy’s (Sep 2019)

- Songs Full of Light - Lafaurie-Peyraguey 1906-2018 (Aug 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Domaine Vincent Dauvissat Chablis (Aug 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: Four From Domaine Raveneau (Aug 2019)

- Two Imaginary Boys: Pichon-Lalande (Aug 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1904 & 1948 Langoa-Barton (Aug 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 Domaine Jean-Louis Grippat St-Joseph (Aug 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury Meursault Les Perrières 1er Cru (Jul 2019)

- Vinous Table: TentaziOni, Bordeaux, France (Jul 2019)

- Precious Clay: L’Eglise-Clinet 1929–2015 (Jul 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1997 Domaine Servin Chablis Vaillons 1er Cru (Jul 2019)

- "G" Acte 1 to 8 (Jul 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1959 Domaine Duroché Gevrey-Chambertin Lavaut Saint-Jacques 1er Cru (Jul 2019)

- Finally: Bordeaux 2015 In Bottle (Jul 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Felton Road Pinot Noir Cornish Point (Jul 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Domaine Georges Roumier Clos Vougeot Grand Cru (Jul 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Vietti Barolo Riserva Villero (Jun 2019)

- Abreu – The 2009s Revisited (Jun 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Gallais Bellevue (Jun 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Champagne Christophe Baron Brut Nature Les Hautes Blanches Vignes (Jun 2019)

- Finding Filhot: Filhot 1935-2015 (May 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Weingut F.X. Pichler Riesling Smaragd Unendlich (May 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992-2011 Louis Jadot Gevrey-Chambertin Clos St.-Jacques 1er Cru (May 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1934 Cheval Blanc (May 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1969 Caves des Liards Montlouis Demi-Sec (May 2019)

- Bordeaux 2018: Back in Black (Apr 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2014 Domaine d’Eugénie Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru (Apr 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 and 2013 Quinta do Noval: The Latest Releases (Apr 2019)

- The Margaux Paragon: Rauzan-Ségla 1900-2015 (Apr 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: 2019 New Releases (Apr 2019)

- An Education: La Dominique 1989-2015 (Apr 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Ausone (Apr 2019)

- Setting Sail - Malartic-Lagravière 1916 - 2013 (Apr 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2012 Domaine G. Roumier Morey-Saint-Denis Clos de la Bussière 1er Cru (Apr 2019)

- What Nectar!! Suduiraut 1899-2015 (March 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1921 Marc Brédif Vouvray Moelleux (March 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Domaine Philippe Foreau (Clos Naudin) Vouvray Moelleux Goutte d'Or (Mar 2019)

- A Test Of Greatness: 2009 Bordeaux Ten Years On (March 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Kistler California Cabernet Sauvignon Veeder Hills Vineyard (March 2019)

- Outsider Looking In: Sociando-Mallet 1982-2015 (March 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Egon Müller Scharzhof Scharzhofberger Riesling Beerenauslese (Feb 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Ravenswood Pickberry Vineyard (Feb 2019)

- Cellar Favorites: 1953 & 1975 l’Angélus (Feb 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Domaine Ponsot Clos de la Roche Vieilles Vignes Grand Cru (Feb 2019)

- Looking The Part: Pichon-Baron 1953 – 2015 (Jan 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Domaine Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier Nuits Saint-Georges Clos de la Maréchale 1er Cru (Jan 2019)

- The DBs: Bordeaux 2016 In Bottle (Jan 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Larcis Ducasse (Jan 2019)

- 2016 Bordeaux…It’s All In The Bottle (Jan 2019)

- Long Distance Runner: Brane-Cantenac 1924-2015 (Jan 2019)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Domaine Armand Rousseau Bourgogne Blanc (Jan 2019)

- Cellar Favorites: Coutet Cuvée Madame (Jan 2019)

- 2018

- Cellar Favorites: 1945, 1966 & 1982 Gruaud Larose (Dec 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Château de Fieuzal Rouge (Dec 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Gaja Barbaresco Costa Russi (Nov 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Luciano Sandrone Nebbiolo d’Alba Valmaggiore (Nov 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1942 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Richebourg “Vigne Originelle Française” (Nov 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2010 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis Blanchot Grand Cru (Nov 2018)

- Enigma Variations: Lafleur 1955-2015 (Nov 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1956 Château Léoville Barton (Oct 2018)

- Where Value Lies: First Look At 2016 Bordeaux (Oct 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1955 Cantina Mascarello Barolo (Oct 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 & 1995 Mayacamas Cabernet Sauvignon (Oct 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine Henri Jayer Vosne-Romanée Cros-Parantoux 1er Cru (Oct 2018)

- Fairest of Them All: Cos d’Estournel 1928 – 2015 (Oct 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Niebaum-Coppola Rubicon (Oct 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1955 Domaine Henri Bonneau Châteauneuf-du-Pape Réserve des Célestins (Sep 2018)

- Sharing Alike: Petrus 1947 - 2015 (Sep 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 Domaine Pierre Morey Meursault Les Perrières 1er Cru (Sep 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Cantina Mascarello Barolo (Sep 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Domaine Alain Voge Cornas Les Vieilles Vignes (Sep 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo (Aug 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1906 Château d’Arche Crème de Tête (Aug 2018)

- Cellar Favorites: Château Lanzerac: 1961 – 1968 (Aug 2018)

- Aiming High: Haut-Condissas 1997–2015 (Aug 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Fontodi Chianti Classico (Aug 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Domaine Armand Rousseau Gevrey-Chambertin (Jul 2018)

- The Marital Margaux: d’Issan 1945-2015 (Jul 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1900 Château Margaux Deuxième Vin (Jul 2018)

- Cellar Journal – Bordeaux to Start… (Jul 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Fratelli Alessandria Barolo Monvigliero (Jul 2018)

- Looking Back To Go Forward: Lafite-Rothschild 1868 – 2015 (Jul 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Domaine Gentaz-Dervieux Côte-Rôtie Côte Brune (Jul 2018)

- In Excelsis: Château Latour 1887 – 2010 (Jul 2018)

- Cellar Favorites: Laville Haut-Brion (Jul 2018)

- Bordeaux In Excelsis (Jun 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1955 Château Latour (Jun 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1937 Château Coutet (Jun 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1961 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Grand Cru (Jun 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1961 Latour-à-Pomerol (Jun 2018)

- Last Man Standing: Bel-Air Marquis d’Aligre (May 2018)

- Cellar Favorites: David Abreu – Revisiting the 2008s (May 2018)

- A Century of Bordeaux: The Eights (May 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Montrachet (May 2018)

- Purple Reign: La Conseillante 1966-2015 (May 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Jurançon Moelleux Le Clos Joliette (May 2018)

- 2017 Bordeaux: The Heart of the Matter (May 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1948 Taylor Fladgate Vintage Port (May 2018)

- 2017 Bordeaux : Au cœur de l'affaire (May 2018)

- The F-Word: Bordeaux Left Bank 2017 (May 2018)

- The F-Word: Bordeaux 2017 (May 2018)

- The F-Word: Bordeaux Right Bank 2017 (May 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Cos d’Estournel (Apr 2018)

- Mother & Child: La Lagune 1962 – 2015 (Apr 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Tertre Rôteboeuf (Apr 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 Heidsieck & Co. Brut Rosé Dry Monopole (Apr 2018)

- A Beautiful Stay: Beau-Séjour Bécot 1970-2015 (Apr 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1973 Pétrus (Apr 2018)

- Vinous Table: TentaziOni, Bordeaux, France (Apr 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: Château Latour: Latest Releases (Apr 2018)

- Bordeaux 2014: The Southwold Tasting (Mar 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: Jadot’s 2015 Beaune 1er Cru Celebration (Mar 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira – Recent Releases (Mar 2018)

- Here We Go Again: Value Bordeaux 2015 (Mar 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Thierry Allemand Cornas Chaillot (Mar 2018)

- Long and Winding Road: Ausone 1912–1999 (Mar 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Troplong Mondot (Mar 2018)

- 2015 Bordeaux: Every Bottle Tells a Story... (Feb 2018)

- The Magician’s Fool: 1950s Bordeaux (Feb 2018)

- Cellar Favorites: 1870 & 1970 Centenario Colheita Tawny Port (Feb 2018)

- Juxtapose With You: Pétrus, Lafleur & Le Pin (Feb 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Henri Bonneau Châteauneuf-du-Pape Réserve des Célestins (Feb 2018)

- 2008 Bordeaux: A Day In A Life (Feb 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1972 Paul Jaboulet Ainé Cornas (Feb 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Domaine Méo-Camuzet Clos de Vougeot Grand Cru (Feb 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Quintarelli Amarone della Valpolicella Classico (Jan 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: Philip Togni Library Releases: 2007 - 1997 - 1987 (Jan 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1969 Domine Duroché Gevrey-Chambertin Lavaux Saint-Jacques 1er Cru (Jan 2018)

- Cellar Favorite: 1994 Rochioli Pinot Noir West Block (Jan 2018)

- 2017

- Remembering Bob Wilmers (Dec 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Smith Haut Lafitte (Dec 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises (Dec 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Spottswoode Cabernet Sauvignon (Dec 2017)

- Grand Cru Culinary Wine Festival 2017 (Nov 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Taittinger Comtes de Champagne (Nov 2017)

- Remembering Patrick Maroteaux (Nov 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Sperling Riesling Old Vines Okanagan Valley British Columbia (Nov 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 Prunotto Barbaresco Riserva (Nov 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Antinori Tignanello (Nov 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Domaine Dujac Clos de La Roche (Oct 2017)

- Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande 1921-2016 (Oct 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche – Grand Cru (Oct 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Domaine Armand Rousseau Chambertin Clos de Bèze (Oct 2017)

- 1978 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Riserva Speciale Villero (Oct 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1964 Dom Pérignon - Original Release (Oct 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Giuseppe Mascarello & Figlio Barolo Monprivato (Sep 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Bodegas Vega Sicilia Único (Sep 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1971 Dom Ruinart (Sep 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Marchesi di Grésy Barbaresco Gaiun (Aug 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: Three Gems from Giacomo Conterno (Aug 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Jacques Selosse Brut Blanc de Blancs (Aug 7)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Roses de Jeanne Rose de Saignée Le Creux d'Enfer (Jul 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Domenico Clerico Barolo Bricotto Bussia (Jul 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Cave Spring Cellars Indian Summer Select Late Harvest Riesling Niagara Peninsula (Jul 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Armand Rousseau Chambertin-Clos de Bèze (Jul 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche (Jul 2017)

- Cellar Favorites: Abreu: Checking in on the 2007s (Jun 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Alain Hudelot-Noëllat Clos de Vougeot (Jun 2017)

- Cellar Favorites: Seven Classics from Ridge (Jun 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Col D’Orcia Brunello di Montalcino Riserva (Jun 2017)

- Cellar Favorites: Château Latour – 2017 Library Releases (May 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1975 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Bussia di Monforte Riserva Speciale (May 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 Château Gruaud-Larose (May 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey (May 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Schloss Johannisberg Riesling Beerenauslese (May 2017)

- 2016 Bordeaux: It’s Now or Never, Baby (Apr 2017)

- Cellar Favorites: 1973 Krug Vintage & Krug Collection (Apr 2017)

- 2016 Bordeaux: 30 Top Values (Apr 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1991 Vilmart & Cie Brut Cœur de Cuvée (Apr 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Giacomo Conterno Barolo Riserva Monfortino (Apr 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Riserva Falletto (Apr 2017)

- Larcis Ducasse Retrospective: 1945-2014 (Mar 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Domaine G. Roumier Chambolle-Musigny Amoureuses 1er Cru (Mar 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1993 Taittinger Comtes de Champagne Rosé (Mar 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Francesco Rinaldi Barolo La Brunata (Mar 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1970 Beaulieu Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon Private Reserve Georges de Latour (Mar 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Ravenswood Zinfandel Monte Rosso (Feb 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Basserman-Jordan Deidesheimer Kieselberg Riesling Beerenauslese (Feb 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Colgin Cabernet Sauvignon Tychson Hill (Feb 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Domaine G. Roumier Bonnes-Mares Grand Cru (Feb 2017)

- 2014 Bordeaux: A September Surprise (Feb 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Vilmart & Cie Cuvée Creation (Jan 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Quintarelli Veneto Rosso del Bepi (Jan 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Stoney Ridge Gewürztraminer Icewine - Niagara Peninsula (Jan 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Castello di Ama Merlot L’Apparita (Jan 2017)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Domaine Drouhin Oregon Pinot Noir (Jan 2017)

- 2016

- Cellar Favorite: 1974 E. Pira e Figli Barolo (Dec 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1976 Hungarovin Tokaji Aszu Essencia (Dec 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Marotti Campi Lacrima di Morro d’Alba Orgiolo (Dec 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Ridge Petite Sirah York Creek (Nov 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Château Carbonnieux Rouge Grand Cru Classe’ Pessac-Léognan (Nov 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Cantina Vignaioli Elvio Pertinace Barbaresco Marcarini (Nov 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Maison Leroy Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru (Oct 2016)

- 1971 Krug Vintage - Magnum (Oct 2016)

- Cellar Favorites: Taittinger: 1996 & 1995 Comtes de Champagne (Oct 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Domaine J.L. Chave (Oct 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Philip Togni Cabernet Sauvignon (Oct 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Milziade Antano Montefalco Sagrantino Colleallodole (Sep 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Château d’Yquem (Sep 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1976 Hugel Riesling Selection de Grains Nobles (Sep 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Henry of Pelham Riesling Icewine (Sep 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Contini Vernaccia Karmis (Aug 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Willi Schaefer Graacher Dombprost Riesling Beerenauslese (Aug 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Arnaldo Caprai Sagrantino di Montefalco Cobra (Aug 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Fontodi Chianti Classico Riserva Vigna del Sorbo (Aug 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Château Coutet (Jul 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Domaine Weinbach Pinot Gris Altenbourg Quintessence de Grains Nobles Cuvée d’Or (Jul 2016)

- 2007 Long Shadows Vintners Collection Poet’s Leap Riesling (Jul 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2004 Taittinger Comtes de Champagne (Jun 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1947 Cheval Blanc (Jun 2016)

- Cellar Favorites: Abreu 2005 Madrona Ranch & Thorevilos (Jun 2016)

- Cellar Favorites: Two From Bruno Giacosa (Jun 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1993 Dom Pérignon Oenothèque Rosé (May 2016)

- Cellar Favorites: A Duo of Piedmont 2004s (May 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Dujac Fils & Père Vosne-Romanée Aux Malconsorts 1er Cru (May 2016)

- 1929 Louis Roederer Brut (May 2016)

- Mouton Rothschild: 2003-2015 (May 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Vieux Château Certan (May 2016)

- Bordeaux’s Radiant 2015s (Apr 2016)

- 1975 Chappellet Cabernet Sauvignon (Apr 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Cheval Blanc (Apr 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1976 Château Climens (Apr 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Domaine Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier Musigny (Apr 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Riserva Le Rocche del Falletto (Mar 2016)

- Remembering Paul Pontallier (Mar 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Château Latour (Mar 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Spottswoode Cabernet Sauvignon (Mar 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Cerbaiona Brunello di Montalcino (Mar 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Château Palmer (Feb 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1987 Giuseppe Mascarello & Figlio Barolo Monprivato (Feb 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1980 Il Marroneto Brunello di Montalcino (Feb 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Zind Humbrecht Pinot Gris Clos Jebsal Selection de Grains Nobles (Feb 2016)

- Cellar Favorites: 1996 & 1985 Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande (Feb 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Vincent Dauvissat Chablis La Forest – 1er Cru (Jan 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1962 Louis M. Martini California Mountain Pinot Noir Special Selection (Jan 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1996 Armand Rousseau Chambertin – Grand Cru (Jan 2016)

- 2012 Bordeaux: Messages in a Bottle (Jan 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Bollinger R.D. Extra Brut (Jan 2016)

- 2015

- Cellar Favorite: 2003 Cos d’Estournel (Dec 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1914 Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage Collection (Dec 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1983 Léon Beyer Gewürztraminer Selection de Grains Nobles Quintessence (Dec 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Checking in on the Lafon 2010s (Dec 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1953 Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage Collection (Nov 2015)

- 2005 Bordeaux with Tanzer & Galloni (Nov 2015)

- Cellar Favorites: 1976 & 1979 Krug Vintage Magnums (Nov 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Carl von Schubert Maximin Grünhäuser Abtsberg Riesling Trockenbeerenauslese (Nov 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Jean Foillard Morgon Côte du Py (Nov 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Domaine Leflaive Chevalier-Montrachet – Grand Cru (Oct 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2005 Tenuta dell’Ornellaia Masseto (Oct 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1962 Charles Krug Cabernet Sauvignon Vintage Selection (Oct 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Bodega Poesia Poesia (Oct 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1990 Jacques Selosse Brut Blanc de Blancs (Sep 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1998 Seppi Landmann Sylvaner Recolté en Vin de Glace (Sep 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Georges Mugneret Ruchottes-Chambertin (Sep 2015)

- Cellar Favorites: Four Classic Cabernet Sauvignons from Randy Dunn (Sep 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Harlan Estate (Aug 2015)

- Cellar Favorites: 1981 Château Cos d’Estournel and 1981 Château Pavie (Aug 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru (Aug 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Salvatore Molettieri Taurasi Vigna Cinque Querce (Aug 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Three from Domaine Leflaive (Aug 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2011 Miani Malvasia (Jul 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Soter Vineyards Pinot Noir Beacon Hill (Jul 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1975 Travaglini Gattinara (Jul 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2008 Schlumberger Gewürztraminer Cuvee Christine Vendages Tardives (Jul 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1985 Ceretto Barolo Bricco Rocche Brunate (Jun 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Trimbach Riesling Cuvée Frédéric Emile (Jun 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2003 Terlano Pinot Bianco Vorberg Riserva (Jun 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2001 Emidio Pepe Montepulciano d’Abruzzo (Jun 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1988 Montevertine Le Pergole Torte (Jun 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande (May 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1978 Ridge Petite Sirah York Creek (May 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Château Margaux (May 2015)

- 2014 Bordeaux – Les Découvertes: Under the Radar Gems and Sleepers (May 2015)

- 2014 Bordeaux – Vintage Highlights (May 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Tenuta Frassitelli d’Ambra Biancolella dell’Isola d’Ischia (May 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Gems from Robert Weil (Apr 2015)

- 2014 Bordeaux: It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over (Apr 2015)

- 1990 Domaine Jean-Louis Chave Hermitage (Apr 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 Giovannini Moresco Barbaresco Podere del Pajorè (Apr 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1999 Comte Georges de Vogüé Musigny Vieilles Vignes (Apr 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Giuseppe Mascarello & Figlio Barolo Monprivato (Mar 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1989 Trimbach Riesling Clos Ste. Hune Vendages Tardives Hors Choix (Mar 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Bruno Giacosa Barolo Villero (Mar 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti 2011 Échézeaux – Grand Cru (Mar 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1986 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo Brunate (Mar 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2006 Tenuta dell’Ornellaia Masseto (Feb 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1965 Col d'Orcia Brunello di Montalcino (Feb 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Taylor’s 1964 and 1965 Very Old Single Harvest Port (Feb 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1979 & 1988 Egon Müller- Scharzhof Scharzhofberger Riesling Auslese - Auction (Feb 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: Aubert 2005 Chardonnay Lauren Vineyard (Jan 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 2009 Miani Sauvignon Saurint (Jan 2015)

- Cellar Favorite: 1976 R. Lopéz de Heredia Viña Tondonia Rioja Gran Reserva (Jan 2015)

- Le Miracle de Haut-Brion (Dec 2014)

- 2014

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Comte Georges de Vogüé Musigny Vieilles Vignes - Grand Cru (Dec 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Armand Rousseau Chambertin Clos de Bèze – Grand Cru (Dec 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 Jean-Louis Chave Ermitage Cuvée Cathelin (Dec 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 2007 Emidio Pepe Montepulciano d'Abruzzo (Dec 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 2000 J.F. Coche-Dury Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru (Dec 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Roederer 1979 Cristal (Nov 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine G. Roumier 1978 Musigny – Grand Cru (Nov 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Bartolo Mascarello 1986 & 1989 Barolo - Magnum (Nov 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Screaming Eagle 2007 Cabernet Sauvignon (Nov 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Six Epic Monfortinos (Oct 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Salon - Magnum (Oct 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 Dunn Petit Sirah Howell Mountain (Oct 2014)

- Cristal and Icons from Piedmont & Bordeaux (Oct 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 1995 Araujo Cabernet Sauvignon Eisele Vineyard Vieilles Vignes (Oct 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 1992 and 2002 Mayacamas Cabernet Sauvignon (Sep 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 1982 Giacomo Conterno Barolo Riserva Monfortino (Sep 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Montrachet 1988-2004 (Sep 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Krug’s Epic 1966 Vintage [magnum] (Sep 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: Two Glorious 1960s Barolos (Sep 2014)

- 2011 Bordeaux from the Bottle (Jul 2014)

- Bordeaux 2013: Definitely Not the Vintage of the Century (May 2014)

- 2013 Bordeaux: Walking the Tightrope (Apr 2014)

- Vinous Table: L’Univerre, Bordeaux (Apr 2014)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Branaire-Ducru (Mar 2014)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Pavie Macquin (Mar 2014)

- Cellar Favorite: 1966 Maison Leroy Beaune (Jan 2015)

- 2013

- The 2010 Clarets: A Modern Classic (Jul 2013)

- Bordeaux 2012: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (May 2013)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Gruaud Larose (Apr 2013)

- Vertical Tasting of Domaine de Chevalier Rouge (Apr 2013)

- 2012

- 2011 Bordeaux: Dry Whites (Aug 2012)

- 2011 Bordeaux: Sauternes (Aug 2012)

- The 2009 Clarets (Jul 2012)

- The Bordeaux Effect (Jun 2012)

- 1982 Bordeaux at Age 30 (May 2012)

- Bordeaux 2011: Tales of Tannins and Terroir (May 2012)

- Vertical Tasting of Château Magdelaine (Mar 2012)

- Vertical Tasting of Château Trotanoy (Mar 2012)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Lynch-Bages (Jan 2012)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau du Tertre (Jan 2012)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Giscours (Jan 2012)

- 2011

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Cheval Blanc (Oct 2011)

- Bordeaux 2010: The Sweet Wines (Aug 2011)

- Bordeaux 2010: The Dry Wines (Aug 2011)

- Vertical Tasting of Chateau Mouton-Rothschild (Aug 2011)

- The 2008 Clarets (Jul 2011)

- Bordeaux 2010: All That Glitters... (May 2011)

- 2010

- 2007 Bordeaux : Don't Hate Me Because I'm Overpriced (Jul 2010)

- 2008 Sauternes and Barsacs (May 2010)

- Bordeaux 2009: The Best Ever? (May 2010)

- 2009

- The Top Clarets of 2006 (May 2009)

- Bordeaux '08: Far Better Than Expected (May 2009)

- 2008

- 2007 and 2005 Sauternes and Barsacs (Jul 2008)

- 2007, 2006 and 2005 Bordeaux (May 2008)

- 2007

- 2006, 2005 and 2004 Bordeaux (May 2007)

- 2006

- 2004 and 2003 Sauternes and Barsacs (Jul 2006)

- The Annual Red Bordeaux Report (May 2006)

- 2005

- 2003 and 2002 Sauternes and Barsacs (Jul 2005)

- The Annual Red Bordeaux Report (May 2005)

- 2004

- Focus on Sauternes/Barsac (Jul 2004)

- The Annual Red Bordeaux Report (May 2004)

- 2003

- 2001 Sauternes/Barsac (Jul 2003)

- The Annual Red Bordeaux Report (May 2003)

- 2002

- 1999 Sauternes/Barsac (Jul 2002)

- 1982 Bordeaux, 20 Years On (Jul 2002)

- 2001, 2000 and 1999 Bordeaux (May 2002)

- 2001

- 1999 and 1998 Sauternes (Jul 2001)

- 2000, 1999 and 1998 Bordeaux (May 2001)

- 2000

- Cellar Favorite: 2002 Domaine François Raveneau Chablis 1er Cru Montée de Tonnerre (Sep 2017)

- 1998 and 1997 Sauternes (Jul 2000)

- 1999, 1998 and 1997 Bordeaux (May 2000)

- 1999

- 1997 and 1996 Sauternes (Jul 1999)

- 1998, 1997 and 1996 Bordeaux (May 1999)

- 1998

- Focus on Sauternes (Jul 1998)

- 1997, 1996 and 1995 Bordeaux (May 1998)

- 1996

- 1995 and 1994 Bordeaux (May 1996)

- 1993

- The 1990 Clarets...To Have and To Hold (Nov 1993)

- 1990

- Cellar Favorites: Château Latour – New Releases (Jul 2016)

- Cellar Favorite: Torbreck Library Wines (Mar 2022)