Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

A Tribute to Beppe Rinaldi

BY ANTNIO GALLONI | SEPTEMBER 6, 2018

“Barolo must be an austere, powerful wine, without fruit,” Beppe Rinaldi often told me. In his hands, the wines were often just that. But to talk about wine is almost superfluous in looking back at the remarkable life of a man who was first and foremost a cultural and intellectual icon, and a winemaker a close second. Sadly, Rinaldi lost his battle with illness a few days short of his seventieth birthday. He leaves behind a rich, multi-faceted legacy that will live forever under the stewardship of his wife, Annalisa, and daughters Marta and Carlotta.

Beppe Rinaldi in his winery

Beppe Rinaldi, affectionately known as ‘Citrico’ for his acerbic wit, was born on September 17, 1948. Originally trained as a veterinarian, Rinaldi took over the family estate only upon the passing of his father, Battista, in 1992. Rinaldi championed all of the tenets of the traditional school of Barolo, chief among them the steadfast belief that Barolo should be made from the blending of multiple vineyards, a view shared by his cousin, Bartolo Mascarello. He was also an outspoken critic of what he viewed as over expansion within the Barolo region, both when it came to projects he did not think were respectful of the bucolic atmosphere of the Langhe hills, such as the Boscareto Hotel (which he dubbed an ‘eco-monster’) and the increase of plantable hectares of Nebbiolo for Barolo. Rinaldi was equally candid when it came to politics and other social issues, enormously refreshing in today’s world of extreme political correctness.

Piedmont was a very different place when I first started visiting in the late 1990s. Rinaldi, like so many other traditional producers, was completely out of favor with both the press and consumers, with the exception of a handful of Barolo appassionati who sought out the wines. At the time, Rinaldi had 5-6 different vintages for sale, as did pretty much all estates. You could buy as much wine as you wanted. The price? A pittance. Rinaldi was almost embarrassed to take your money. One of the reasons I started writing about wine is because, at the time, there was very little information available about Rinaldi and other traditionally-minded growers, including so many names that today are among the most coveted producers not just in Piedmont or Italy, but the world. Pretty soon, the allure of these wines and the families who made them became an obsession.

Not much has changed over the years at the Rinaldi cellar

It took me a few visits to start to understand the essence of what I was experiencing. Rinaldi’s mind always seemed to race with multiple thoughts. An hour or more might pass before we started tasting. At first I found Rinaldi’s ramblings to be distracting. After all, I was there to taste the wines, and I had a packed schedule of appointments. It didn’t take me long to recognize the errors in my ways. So I started visiting Rinaldi several times a year, often outside of my normal schedule of tastings. I just wanted to soak in everything he had to say. My favorite time to visit was in late August, when Italy starts getting back to work after the summer holidays. The women of the house were often still away and there were no other visitors. These were rare moments of solitude.

One year Rinaldi took us to see his vineyards. On the way, we stopped at Cerequio, one of the tiny hamlets that dot the Piedmontese landscape. Rinaldi wanted to show us the spot where a number of partigiani – the group who fought against the fascists – were executed on August 29, 1944. Many of the dead were young men in their teens. A plaque commemorating their lives is plainly visible on one of the walls of what is now the Chiarlo family’s Palas Cerequio luxury hotel. Later that day Rinaldi made a quick stop at a friend’s house to tend to a sick dog.

One of the Lambretta motorcycle Beppe Rinaldi lovingly restored

Perhaps because of his slightly disheveled appearance and casual demeanor, it might be tempting to think of Rinaldi as a contadino/vigneron who looked after his vines and made superb wines. Although Rinaldi embodies all the best values of the Piedmontese artisan tradition, a few minutes in his office was enough to see he was also a man of immense culture. The walls were covered with books on a dizzying array of subjects. When it came to Barolo, Rinaldi was an ardent student of history. He often spoke of the legacy of the Marchesi Falletti, and seemed to know every line in Fantini’s famous treatise on viticulture and winemaking by heart. A tour of the family home, including the room where Rinaldi was born, spoke to a long-gone era of Italian culture. Rustic interiors and furniture from his parents’ and grandparents’ generations were those of simpler times. The walls were adorned with drawings of Valentina, the famous comic strip character created by renowned artist Guido Crepax, one of Rinaldi’s closest friends. This rich setting spoke eloquently to Rinaldi’s passions for the most basic things in life – family, friendship, wine, food, sex and intellectual pleasure.

Today, the winery is entered through the lower level, but visitors walking through the old reception room upstairs might have noticed a gleaming, lovingly-restored Lambretta motorcycle, one of which Rinaldi famously rode all the way to Sicily. Or the eye might have gravitated to the high-end Barolo corkscrews Rinaldi had made a few years ago, or perhaps to the refurbished 1930’s Leica camera that belonged to his father.

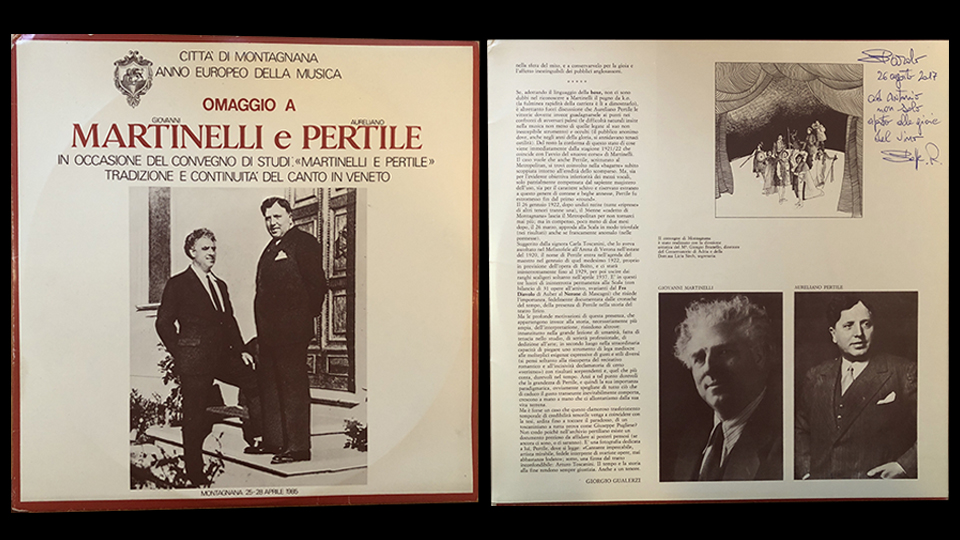

“Would you like a glass of water,” Rinaldi asked me on another recent visit. “You know, the water in Barolo has 2% alcohol,” he added in that broken raspy voice of his. I spent several hours that afternoon with Rinaldi and his wife Annalisa, talking about many subjects, none of them having anything to do with wine. Beppe Rinaldi and I shared a deep love for the opera. Many years prior, I met Magda Olivero, one of the most important verismo sopranos of the 20th century in Rinaldi’s living room. Apparently she was a long time private customer. I liked to believe that perhaps drinking Rinaldi Barolo was one of the reasons she was able to sustain a professional career into her 90s, long after most singers retire. Rinaldi asked me if I knew who Aureliano Pertile and Giovanni Martinelli were. Of course I did. Both were among the leading tenors of the 20th century. Coincidentally, they were both born in Montagnana, a small town in Veneto, within a few days of each other in 1885. Rinaldi insisted on giving me a double LP set, featuring the two tenors, photographed below.

A personal inscription adorns the two-LP set featuring tenors Giovanni Martinelli and Aureliano Pertile

I will hold many other anecdotes close to my heart forever. Like the story of Rinaldi taking a book and a candle into one of his 100 year-old vats to sleep during the torrid summer of 2003. That vat has since been disassembled, but the stories remain. One year, I was finally able to buy a few bottiglioni, the large 1.9 liter format once favored in Piedmont. The bottles were unlabeled. “Here…the least you can do is put the labels and capsules on yourself,” Rinaldi barked at me as he tossed them in my direction. “And bring back the empty bottles, they are family heirlooms,” he added emphatically. That was pretty much typical. Marzia and I were thrilled when Rinaldi accepted our invitation to participate in the very first Festa del Barolo, in 2011. When the microphone passed to him during the tasting, the room fell silent. You could hear a pin drop. All the sommeliers stopped what they were doing and the audience listened in rapt attention as Rinaldi described his first visit to New York (which included touring Manhattan on a Vespa) and shared his philosophy on wine and life. It was a truly magical moment.

Beppe Rinaldi at the inaugural Festa del Barolo

In late 2013, the wines were being pumped over when I visited in the fall. Rinaldi asked if we wanted to taste the young musts. Of course, I answered. A group of young couples, impeccably well-dressed with the finest in Italian fashion, winced when they saw us pour the unfinished wine from our glasses back into the plastic tubs where the musts were being pumped back into the vats. They had surely never seen anything like that! And then there was Rinaldi’s unprintable alternate use for the large wood hammers that are used to dislodge the bungs that keep air out of the casks. But my favorite story dates back to a much earlier visit, sometime around Christmas. I remember we bought some Dolcetto that day, which was what I could afford given my student loans. Rinaldi gave us some salami, made by a friend, that he was aging in his cellar, along with a jar of peppers marinated in Barolo. The stars were incredibly bright on that crisp, cold winter night. It was a perfect dinner.

Barolo Chinato was one of Beppe Rinaldi’s passions. This hand-designed label (center) is nestled between two 1.9 liter magnums of the super-rare pure Brunate Barolo Riserva

RIP, Citrico, and thank you for the memories.

You Might Also Enjoy

Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo Brunate Retrospective: 1990-2010, Antonio Galloni, May 2017

1986 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo delle Brunate Riserva Speciale, Antonio Galloni, March 2015

Cellar Favorite: 1971 Giuseppe Rinaldi Barolo, Antonio Galloni, August 2018