Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

2021 Barolo: Changing Times, Changing Wines

BY ANTONIO GALLONI | JANUARY 7, 2025

My November trip to Piedmont was one of the most intriguing in recent memory. Producers were living in a sort of suspended state, their thoughts bouncing back and forth from the challenges of the just-concluded 2024 harvest to excitement over the soon-to-be-released 2021s and the outcome of the recent presidential election in the United States. Against that very colorful background, I tasted a stunning array of new releases. The 2021 Barolos are finessed, elegant wines that will delight Piedmont fans.

Our annual report surveys the latest from a wide range of producers and includes notes on Piedmont’s everyday wines, bottles that I consider just as essential when it comes to appreciating the region’s rich oenological landscape. The pace of change continues to be fast. This year I tasted wines from several producers who were new to me. The explosion of new wineries and projects is one of the most exciting trends in Piedmont today.

Ileana and Paolo Giordano, seen in their small garage winery in Perno, began bottling their estate Barolo only with the 2018 vintage. The wines have gotten better and better since then.

2021 Barolo: Cutting to the Chase

Two thousand twenty-one is a superb vintage for Barolo. Many of the entry-level Barolos (often referred to as normale or classico) are terrific, always a sign of a good year. Readers will find a bevy of outstanding wines in this report. The 2021s are marked by good color, open aromatics, pliant fruit and finessed, ripe tannins. At the very pinnacle of excellence, the finest 2021s are compelling and profoundly expressive of place. They are richer than the generally austere 2019s but more vibrant than the open-knit 2020s, making 2021 the most harmonious and consistent of the group. In the final analysis, 2021 is a vintage marked by high average quality. The only thing missing is perhaps the stratospheric peaks of the most exceptional years. It is a vintage that readers will want to explore with great attention, especially considering that Mother Nature was much less generous with her bounty in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

‘Ring a lot, but not too much!’ reads the sign at the entrance to the Giuseppe Rinaldi winery in the heart of Barolo.

The 2021 Growing Season

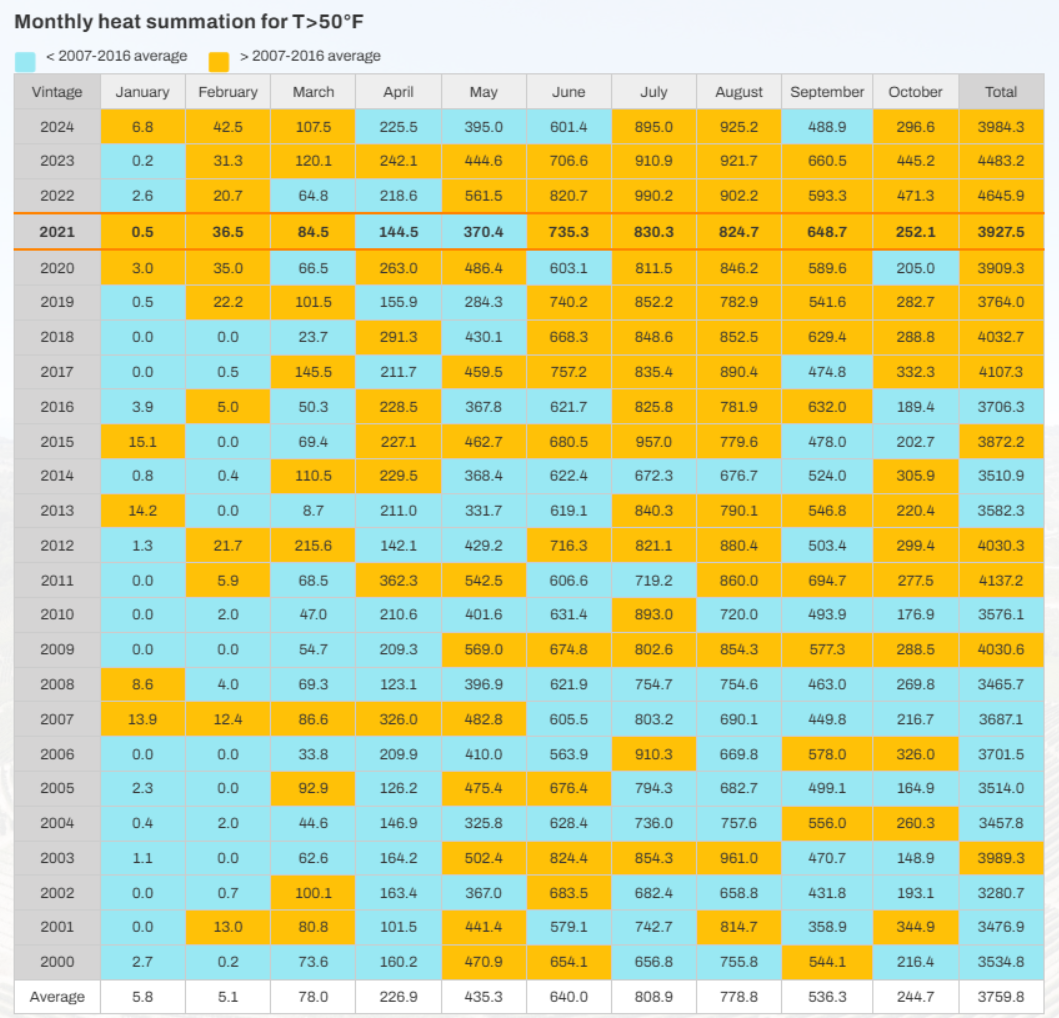

By most accounts, 2021 was a relatively benign season, except for a few highly localized shock events. The year got off to an early start before temperatures cooled a bit in April and May. Heat summation data shows that 2021 was warmer than the 20-year average, notably in the summer months of June through September. Although temperatures remained elevated throughout the summer, there were no spikes or periods of abnormally high heat. Rainfall was lower than normal, but precipitation in the preceding winter was no doubt beneficial, as were well-timed summer showers. “We did start to see some heat stress at the end of the year,” Alex Sánchez explained at Brovia. “A little stress for vineyards is a positive. Stress, but not torture.”

Two thousand twenty-one was not without its challenges. Severe frost in April reduced the crop in several top sites. Brovia lost 50% of their production in Garblèt Sue'. Nicola and Stefania Oberto at Trediberri suffered similar losses in Rocche dell’Annunziata. Similarly, sisters Marta and Carlotta Rinaldi endured crippling frost in Brunate that eventually led to a significant replanting of the vineyard. Devastating hail in mid-July was especially damaging in nearby Roero and Monferrato but also made itself felt in a few sites in Barolo.

Harvest took place between the end of September and mid-October for most properties. “Everything ripened at once,” Eugenio Palumbo explained at Vietti. “We picked all the crus between September 30 and October 3, except for Ravera, which always ripens about a week later. Other producers picked well into October, including Vajra, where the Nebbiolo harvest wrapped up on October 21.

Monthly heat summation data, compiled by Alessandro Masnaghetti, shows that 2021 was warmer than average in nearly every month. Readers should keep in mind that Masnaghetti’s historical average runs from 2007-2016, a period chosen because it includes a wide range of years but not a trailing period, which would be more common. Nevertheless, the data in the chart shows the same readings for vintages 2014 through 2024 by month. © Enogea, used with permission.

How much does this really matter? Not all that much, in my opinion. For example, harvest dates are interesting to contemplate, but producer style, yields, location and size of winery create high levels of variability that make it very difficult to extrapolate meaningful conclusions that are then reflected in the wines themselves. Today, wine writing increasingly focuses on data. Harvest dates, alcohols, pHs, maceration times and a whole range of other variables can easily be measured. I admit it, there is something reassuring about data, something that is certain in the art of evaluating the wonderful, mysterious and dynamic beverage that is wine. But I am starting to see too much reliance on numbers and not enough emphasis on offering original, unbiased opinions based on actually tasting wine. And that’s a problem, as I will explain below.

A typical tasting at Vietti. On this day, it was all the 2021, 2022 and 2023 Barolos and Barbarescos, plus the entry-level offerings.

What Makes a Great Barolo Vintage: Looking at 2021

Over the last several years, I have shared my model of what makes a great Barolo vintage. It is the sum of everything I have learned from many people, organized in a way that pulls all that information together. Compared to Bordeaux, Piedmont has yet to establish a formal framework for evaluating vintages. Many people have views, but I have never seen them codified. What follows is my set of objective criteria necessary for a Barolo (or Barbaresco) vintage to be considered truly great. This framework is inspired by the late Denis Dubourdieu and the model he developed for assessing Bordeaux vintages. To that, I add my 25-plus years of visiting Piedmont and all the data I have collected in speaking with winemakers, agronomists and other professionals over that time, plus drinking more than my fair share of the wines. As with Dubourdieu’s model, this framework addresses the growing season and does not examine the actual wines.

Naturally, this model is created in the present day. It won’t apply as well to vintages from previous eras, especially vintages from the 1950s-1970s. At that time, warm weather was considered ideal because grapes struggled to ripen. The warmest vineyards, those that faced due south, the famous sorís, were the most coveted. Today, in our climate change-challenged world, you would be hard-pressed to find a producer who believes that south-facing vineyards are the most ideal.

Fabio Alessandria turned out some of the most compelling Barolos of the 2021 vintage at G.B. Burlotto. As good as the top wines are here, the entry-level bottlings are every bit as compelling. Alessandria is seen here in his winery in November 2024, with his iconic Barolo Monvigliero still on the skins.

Let’s Examine 2021:

1. A Long Growing Season – A long growing season, defined as the period from bud break to harvest, is essential for achieving full physiological ripening of the fruit, skins and seeds. Since Nebbiolo is a highly tannic grape, less than full physiological ripeness is heavily penalizing. In 2021, the growing season got off to an early start, while the timing of harvest was more or less average by present-day standards, which resulted in a fairly long cycle and permitted for the full ripening of tannins. The first condition was met.

2. Diurnal Shifts – The final phase of ripening must be accompanied by diurnal shifts, which are the swings in temperature from warm days to cool nights. Diurnal shifts create aromatic complexity, full flavor development and color. In 2021, evening temperatures cooled down at the end of the season to balance daytime highs. Thus, the second condition was met.

3. The Absence of Shock Weather Events – Frost and hail can severely and irreparably damage the crop. Similarly, periods of uninterrupted elevated heat can block maturation. Frost and hail were issues in some spots, but their impact was localized. Although temperatures were high during the summer months, there were no heat spikes or other shock events to speak of. Therefore, the third condition was mostly met.

4. Stable Weather During the Last Month – The last month of the growing season makes the quality of the vintage. Stable weather without prolonged rain episodes is essential for harvesting a healthy crop. Weather during harvest was largely uneventful. The fourth condition was met.

5. A Late Harvest – Harvest must take place in October (possibly late September in some areas), with the final phase of ripening occurring during the shorter days of late September and October, as opposed to the longer, hotter days of August. By present-day standards, harvest was on the early to average side for most estates. The fifth condition was mostly met.

All in all, the model does a pretty accurate job of capturing the key takeaway, namely that 2021 has a lot going for it. Conditions were very good, but also just short of exceptional.

Mariacristina Oddero, flanked by niece Isabella (left) and son Pietro (right). The Odderos are making some of the most compelling wines in Piedmont.

Evolutions in Winemaking

“Great wines are made in the vineyard,” says the popular refrain. Nothing could be further from the truth. Grapes for making wine are made in the vineyard. Wines are made in the cellar. Vintage 2021 in Barolo is a perfect case in point. Whatever conditions and/or potential the growing season may have presented, the wines themselves are just as marked by choices producers made in the cellar, if not more so.

By far the biggest change I have seen in winemaking in the Langhe in recent years has been a move toward greater vibrancy. Picking for freshness, lighter extractions and a more thoughtful approach to cooperage are all part of the modern-day lexicon. Of course, these are the same developments that are shaping wines in many, if not most, regions around the world. Even so, I see many Barolos today veering into the realm of the excessively light. There is room for a wide range of styles in Barolo, as in every region. I have always maintained that diversity is far better than standardization. I think that is obvious. Leaving aside very aged wines or the most rain-plagued vintages, Barolo has never been a light wine. Barolo is not Trousseau. So, when is the line crossed? For me, that is when vineyard-designate Barolos are so light and washed out that they no longer express the signatures of place. Increasingly, many Barolos are approaching this point. Some have crossed it. These Barolos come across as emaciated and gaunt, like a person who is malnourished. The wines are just as uninteresting as the excessively oaked, heavily extracted Barolos of the 1990s and 2000s, in the inverse. They lack the single most critical attribute of a single-vineyard wine: the indelible stamp of place.

I have seen this movie before. In the early 2010s, the In Pursuit of Balance movement in California sought to promote wines with lower sugars, lower alcohols and less opulence than what were viewed as the critically successful wines of the day. The overall discourse was healthy for wine, but as so often happens, good intentions lead to overshooting in the opposite direction. Slowly, producers began to retreat from In Pursuit of Balance. The wines weren’t aging well, they weren’t selling well, and they weren’t balanced, either. In time, producers began to find a more measured approach, and that’s when the wines started to achieve true balance, a point of equilibrium between two extremes. I expect that will happen here as well.

The cavernous cellars at Cavallotto hold a number of wines, including new Barolos from Villero and Rocche di Castiglione.

How Will Today’s Barolos Age?

This is one of the questions I am most frequently asked. Will today’s Barolos age as well as the best wines from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s? I wish I knew the answer. It’s a tough question, one that involves a great many factors. Most often, readers ask about ageability in connection with climate change. That’s understandable, given that climatic conditions have changed markedly over the last several decades. But there’s more to it than that.

Starting in the vineyards, farming approaches have shifted dramatically in favor of lower intervention and more sustainable practices. The concept of “sustainability” has been around for no more than a decade or so, at the very most. “We used to use more copper in the vineyards,” Marta Rinaldi told me recently. “Skins were harder, and as a result, my father’s wines had more color than what we see today.” Much the same can be said for fertilizers and other products that were once used widely.

Of course, climate change is a big issue. Patterns of heat and rain are very different today than they were a generation ago. Most old-timers cite 1985 as the first vintage with very warm weather, but that is relative, as conditions of what were considered “warm” vintages at the time would seem quite average today. But there is no doubt the trend is toward warmer seasons, and even more critically, drier years. As a result, alcohols have begun to creep up to levels never seen before, in the most extreme cases. That can be a problem, because Nebbiolo is a variety that naturally carries more alcohol than many other red grapes to begin with. For example, a comparison of Barolo versus Burgundy and/or Bordeaux will show that in any given era Barolos tend to be higher in alcohol than the reds from France’s most famous regions.

Vittore Alessandria in the historic cellars of his family’s Fratelli Alessandria winery in Verduno. Alessandria crafts elegant, nuanced Barolos from top sites in Verduno and Monforte d’Alba.

As I have written before, so far, Piedmont has been a net beneficiary of climate change. Good to exceptional vintages are more common than they once were. Nebbiolo was traditionally a very hard grape to destem because grapes have to be fully ripe to detach from the stem, and achieving full ripeness was a challenge. Today, with more ripeness and better destemming machinery, this is no longer an issue. Stated from a different angle, it is safe to assume that wines from the 1950s and on had a fair amount of stems and jacks that made it into the tanks. Winemaking is far gentler than it once was. Cooperage choices today often favor large-format wood over small French oak barrels. As a result, today’s wines often drink well on release. That, in turn, has contributed to a massive surge in popularity.

It was not always like this. I remember buying the 1996s on release. They were hard as nails. The 1997s were more giving, but this was the era of hugely extracted, oaky Barolos. Many 1998s were also impenetrable at the outset. That is rarely the case these days. Other wines were marred because of a lack of cleanliness in the cellar, something else that, thankfully, belongs to the past. When I think of the 2021s in this report, many of them are hugely enjoyable now, others will drink well in a few years, and only a few require extended cellaring. That’s quite a change. How will today’s wines age over the long term? I don’t know, but it will be interesting to find out.

Tasting wines from barrel at Cappellano provides an early look at how upcoming releases are developing in the cellar.

On Bottling & Corks…

Probably of greater relevance and importance to most consumers is not how Barolo will age several decades out, but how the wines are developing in more medium-term time frames.

I was fortunate very early on to find an audience for my writing, first at Piedmont Report, then The Wine Advocate and now at Vinous. By far, the most rewarding aspect of the last 20 or so years has been getting to know so many other fellow wine lovers around the world. I cherish every opportunity to exchange views with readers who have a deep passion for wine, and for Piedmont wines more specifically in this case. Those conversations have given me tremendous insight into what consumers are seeing and tasting.

Similarly, I was very lucky to be exposed to Barolo and Barbaresco at a very early age, thanks to my parents. In short, I have been buying and drinking these wines since I was a young adult. That means vintages back to the early 1990s. A recently completed inventory of my cellar shows that I own more than 3,000 bottles of Barolo and Barbaresco. I am not sharing that figure to show off, but rather because I am not a critic or a taster who hands out high scores like candy. I am, first and foremost, a wine lover and consumer with a significant investment in Piedmont. I don’t mean that financially (although that matters too), but more emotionally. I bought my wines with an eye toward the future. When a bottle does not show as it should, I feel the same pain as every other consumer who is reading this and who has had similar experiences.

I have written that generational transition is the single biggest risk for estates in Piedmont (and Italy, for that matter) today. That remains true for the medium and long term. But there is a much bigger threat, and it is here now. It is not climate change, the state of the market or shifting consumer preferences. It is a much more insidious problem: an unacceptably high percentage of flawed bottles for some producers, more than what I see in the other regions I cover. So far, this problem appears to be relatively contained, but it does not take much for it to spread if producers are not extremely vigilant.

While I do not wish to be alarmist, nor paint an entire region with a broad brushstroke, these issues need to be addressed openly and constructively with the goal of finding solutions.

Elio Sandri’s newest Barolo emerges from a small parcel planted with the Michet clone of Nebbiolo.

At best, flawed bottles are relegated to simple “bottle variation.” At worst, they end up in the kitchen sink. There are many reasons why bottles can be flawed, but there are at least two that are obvious and that merit further exploration here. The first of these is bottling, which is a highly technical process. Ensuring that every bottle is consistent, from the first to the last, is extremely difficult. The most critical factor is the exposure of wine to oxygen during bottling. If some bottles are exposed to more oxygen during bottling, those bottles will mature faster. It’s that simple.

I have long been a staunch advocate of producers owning their bottling line in order to control every step of production. This is the norm in Piedmont. Historically, wineries had staff that could handle the technical aspects of operating a bottling line. But technologies change. Times change. Perhaps wineries are no longer able to deal with the rigors of complex machinery that is only used a few days per year. To be sure, the wines are no longer the artisan, homemade Barolos of the past, but rather world-class wines that are being served next to the other elite bottles from around the world. The standard for excellence is higher, while the margin for error is much lower.

A more obvious culprit is corks. Some producers in Piedmont are obsessed with corks. But not all. As much as farming, viticulture and making wine require a total focus on quality, the same applies to corks. Many estates will divide their sourcing among two or three suppliers in order to mitigate the risk of losing a significant amount of their production to a bad batch of corks. That seems reasonable, until one batch is tainted and 50% of a wine is ruined. Unfortunately, I have seen it happen.

Another concern is the possibility that changes in viticultural practices mentioned above may be resulting in wines that are aging faster than desired. The use of SO2 during aging and bottling is another topic that is worthy of greater exploration. These are complex subjects, above my pay grade as the saying goes. I do hope that those with the technical expertise to tackle these problems will do so. Most Barolos (and Barbarescos) are bottled in the summer, which is about six months away as of this writing. That’s enough time for every single producer to seriously think about their bottling processes and cork sourcing. I cannot overestimate how serious of an issue this is.

About This Report

I tasted most of the wines in this report during a trip to Piedmont in November 2024, followed by several additional tastings in our New York offices. Although this report focuses on the 2021 Barolos, I also include notes on everyday wines, the best of which offer plenty of regional and varietal character, but at prices that make them far more approachable than the most coveted Barolos. In a few instances, entries in this article only include entry-level wines because the top bottlings have either recently been reviewed or are still in barrel.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or re-distributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright, but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

2020 Barolo: Selective Excellence, Antonio Galloni, January 2024

2020 Barolo: Part Two, Antonio Galloni, September 2024

2019 Barolo: Back on Track, Antonio Galloni, January 2023

The 2018 Barolos, Part 2, Antonio Galloni, October 2022

The Enigma of 2018 Barolo, Antonio Galloni, February 2022

2017 Barolo, Part 2: The Late Releases, Antonio Galloni, October 2021

2017 Barolo: Here We Go Again…, Antonio Galloni, February 2021

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Accomasso

- Alessandro e Gian Natale Fantino

- Andrea Oberto

- Armando Parusso

- Azelia

- Barale Fratelli

- Bartolo Mascarello

- Benevelli

- Borgogno e Carbone

- Bosco Agostino

- Bovio

- Brezza

- Brovia

- Burzi

- Ca' di Press

- Canonica

- Cappellano

- Carlo Revello & Figli

- Ca' Rome

- Cascina Bongiovanni

- Castello di Verduno

- Cavallotto

- Ceretto

- Chionetti

- Conterno-Fantino

- Conterno-Nervi

- Cordero di Montezemolo

- Cordero Mario

- Cordero San Giorgio

- Crissante Alessandria

- Diego Conterno

- Elio Altare

- Elio Grasso

- Elio Sandri - Cascina Disa

- Enzo Boglietti

- E. Pira (Chiara Boschis)

- Ferdinando Principiano

- Francesco Boschis

- Francesco Clerico - Ceretto

- Francesco Rinaldi & Figli

- Francesco Versio

- Fratelli Alessandria

- Fratelli Revello

- Fratelli Serio & Battista Borgogno

- G.B. Burlotto

- G.D. Vajra

- Giacomo Conterno

- Giacomo Fenocchio

- Giacomo Grimaldi

- Gianfranco Alessandria

- Gian Luca Colombo

- Giovanni Corino

- Giovanni Rosso

- Giuseppe Rinaldi

- Icardi

- La Spinetta

- Luciano Sandrone

- Luigi Baudana

- Luigi Pira

- Malvirà

- Marcarini

- Marco Bonfante

- Marengo

- Margherita Otto

- Marziano Abbona

- Massolino

- Mauro Molino

- Mauro Veglio

- Michele Chiarlo

- Orlando Rocca

- Paolo Giordano

- Paolo Scavino

- Pecchenino

- Philine Isabelle

- Pianpolvere Soprano

- Pio Cesare

- Podere Rocche dei Manzoni

- Poderi Aldo Conterno

- Poderi e Cantine Oddero

- Poderi Luigi Einaudi

- Renato Corino

- Roberto Voerzio

- Roccheviberti

- Silvano Bolmida

- Trediberri

- Vietti