Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Buy Some, Try Some: Beaujolais 2022-2024

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 17, 2025

Thirty-one.

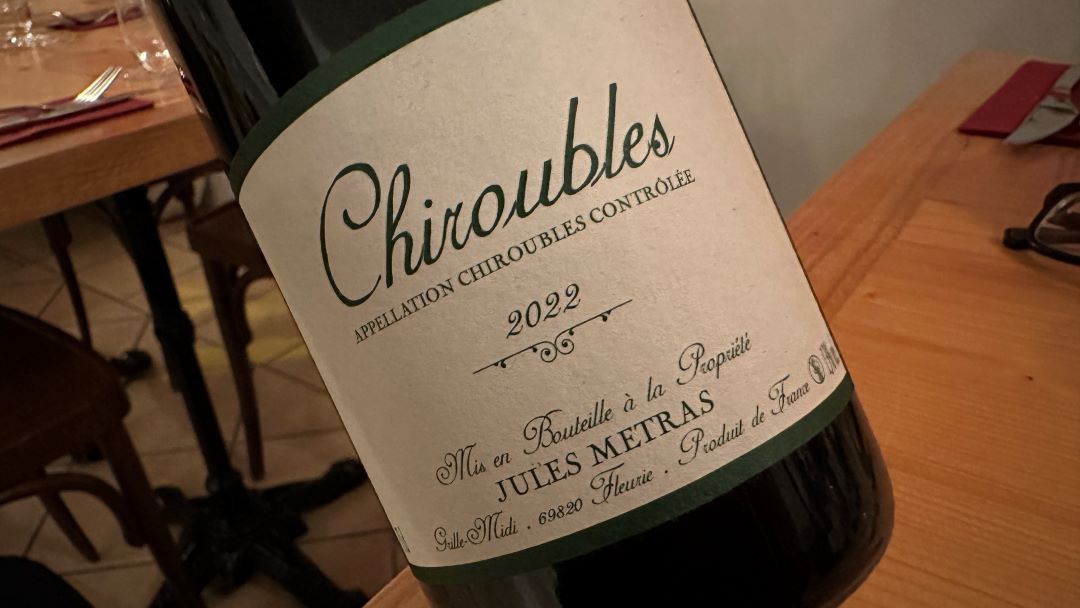

A Chiroubles from Jules Metras glistens like a cut ruby. The nose onomatopoeically “pings” with Morello cherries and wild strawberries. It makes me think of a young child, arms out wide, spinning round and round in circles without a single care in the world. It tastes life-affirmingly vibrant and citrus-fresh. It shimmers with nascent energy, yet there is genuine complexity, with a crystalline finish rendering it impossible to resist another sip.

The price? Thirty-one euros.

That’s the restaurant price.

So, if there is a Beaujolais-shaped hole in your heart, then it’s time to fill it. Maybe you need a wake-up call, and I’m only too happy to provide it. Do you give Beaujolais a steer for the heinous crime of being unbeatable value-for-money, because, and I hate to use the “c” word, it’s too cheap, just like that Chiroubles? Cheapness equates to low quality…doesn’t it?

C’mon. You’re cleverer than that.

Beaujolais has reinvented itself over the last two decades. It’s time to expand your horizons beyond the Pinot Noir that you begrudgingly shell out for each year, much of it now too expensive to drink. Your tastebuds will be eternally grateful, and so will your bank account.

As usual, I visited Beaujolais in early March, when the serried rows of goblet vines that look as if they’ve been screwed into the hillsides are rubbing the sleep from their eyes as the new season dawns. Vines were more dormant than usual since the first three months of 2025 had been colder than normal. It was a “proper” winter, to quote one vigneron, beneficial for killing bugs and viruses and for allaying fears of a late spring frost wreaking havoc after a tumultuous 2024 saw lower yields (albeit not to the devastating degrees of some parts in the Côte d’Or or Chablis). On the other hand, winemaker Mee Godard drove home the financial precipice she faces: “Some of my vineyards were damaged by frost,” she rued. “I still picked the fruit, but if it happened again, I might not.” In other words, the cost of labour means she would lose money on each bottle, even though Godard justifiably charges more for her wines than many of her peers.

Vines were just emerging from an unusually long dormancy when I visited in March.

My days in Beaujolais followed the same pattern as in previous years: tasting at Inter Beaujolais’ offices in order to cast the net wide, numerous producer visits in the afternoons, and dinners where I met new winemakers and got the lowdown on the region. This report focuses on 2023s that are in bottle and hitting shelves, augmented by 2022s, bottled 2024s that undergo a brief élevage, and unfinished samples from barrel. I hope to augment these 500+ notes with more in the coming weeks, since some producers “evaded capture.” Readers should note that I included Beaujolais wines made by Burgundy-based producers, such as Thibault Liger-Belair, Louis Boillot and Lafarge (Lafarge-Vial), in January’s Burgundy 2023 report.

Without further ado, let’s examine the growing seasons.

The Growing Seasons

Two thousand twenty-three was a season cut from a similar cloth to the “solar” 2022 vintage that witnessed the hottest August since 1959. Edouard Parinet at Château du Moulin-à-Vent dubbed 2023 a “bizarre” vintage. Budbreak took place between April 4 and 9, around the same time as in 2021. Clement and warm weather in the final week of May predicated an even flowering in the first week of June, though mi-floraison was just over a week later than normal. Mid-June saw some outbreaks of black rot on nascent bunches. July was a degree warmer than usual. Hot conditions led to hailstorms on July 9, with localised damage two days later. There was also some botrytis at the beginning of that month.

Véraison took place between July 24 and August 1. The weather then changed with a cool spell at the beginning of August—1.8°C below average—before it swung the other way with temperatures reaching the high 30s. This triggered more hailstorms on August 13 that were particularly acute in Régnié and Morgon. The mercury remained high, 3.2°C higher than average in the first week of September and hotter than it had been in July. The heat exacerbated evaporation and served to reduced berry size, particularly in younger vines that suffered more stress. More storms affected northerly appellations on September 12, with hail again on September 13 in Morgon. Fortunately, many had completed picking by that time.

Georges Descombes, the unofficial fifth member of the famous “Gang of Four,” pictured during my first visit in Beaujolais.

Harvest commenced around August 28 for Chardonnay and around August 31 for Gamay. Some pickers brought their planned harvest date forward due to rapidly escalating sugar levels. “We tried to pick as quickly as possible,” winemaker Sonja Geoffray told me, “But it still took two weeks, so there was quite a difference in ripeness levels.”

The number of bunches per vine was 13% higher than the 33-year average, the same as 2022. Bunches tended to have more berries per bunch, yet berry weight was 27% lower than normal due to the aforementioned evaporation in August and early September (the lowest after 2003, 2015, 2020 and 2022). In total, yields were 14% above the 33-year average.

It is interesting to compare the analysis of berries provided by the research centre SICAREX. At 13.0%, alcohol levels for 2023 are around half a degree less than in 2022, though higher than the 2021 average of only 11.6%. Tartaric acid is slightly down in 2022, but there is a little more malic and pH levels are a little higher, comparable to 2015 and 2018. Some winemakers such as Lapierre conducted slightly shorter carbonic maceration.

Beaujolais’s 2024s constitute my first encounter with 2024s amongst the regions that I cover for Vinous, with Bordeaux to follow imminently and, later in the year, Chablis and the Côte d’Or. Two thousand twenty-four already has an unenviable reputation as a wet and hail-struck season in which Mother Nature refused any reprieve. Rain was incessant; according to Louis-Benoît Desvignes, there was 1,100 mm, which is around 400 mm more than average. Many winemakers bemoaned the constant difficulties of treating the vines during infrequent and brief spells of dryness, lest rain wash away hours of hard work. Many of Beaujolais’ vineyards are steep, more so than the Côte d’Or, making them impossible to work by tractor. Not for the last time, winemakers put on brave faces with claims of “pleasant surprises.” Of course I empathise, but I must uphold objectivity and, whilst I have no doubt that some wines will defy expectations, it is not going to be a season fecund with great wines. I keep an open mind, as ever.

Beaujolais accommodates a variety of approaches, from large-volume commercial enterprises to artisanal natural wine producers. On the left, four of the leading low-intervention winemakers, from front to back: Julien Sunier, David Beaupère, Antoine Sunier and Paul-Henri Thillardon. On the right, winemaker Sonja Geoffray at Château Thivin in Côte de Brouilly.

The Wines

The 2022 and 2023 vintages make interesting bedfellows. The hot summer in 2022 challenged winemakers to apply restraint in both the vineyard and the winery and begat opulent, powerful, slightly higher-alcohol wines. Inevitably, the cream rises to the top. I find that Gamay relishes warmer climes more than Pinot Noir, though push Gamay too far and you lose the vital freshness that defines great Beaujolais.

The 2023 vintage was a different test altogether. As Richard Rottiers stated, much depended on how soon you picked following the late-August heatwave. Like others, Rottiers had planned to harvest around September 7, but once he inspected his vines and observed rapidly escalating sugar levels, he brought picking forward by a week. This decision bifurcates quality in 2023 between those who managed to capture freshness and marry it with the season’s ripeness, and others who either chose to wait or could not obtain harvesters earlier, thereby risking overripeness that denudes wines of terroir expression and renders them flabby and ponderous.

Where winemakers got it right—and hooray, there are plenty of them—the result is a treasure trove of outstanding Beaujolais that equal or surpass their 2022 counterparts. The 2023s are often suffused with more drinkability and elegance: site-driven Gamays. According to a long-term soil study, Beaujolais has approximately 300 different soils, including metamorphic, sedimentary, volcanic, pink granite, blue schist and golden Pierre Dorées (As a rule of thumb, you find granite underlying northerly appellations and more clay/limestone formations in the south). The best 2023s ably translate this geological tapestry.

I adore this photograph of Philippe Viet and his neighbour, Mee Godard, in Villié-Morgan. It conveys the bond often found between winemakers in Beaujolais.

As I tasted through the region, I perceived two Beaujolais. Perhaps that is because, in order to gain an accurate and unfiltered reflection of the region instead of a limited purview of elite, I do not ignore co-operatives and stalwarts. Moreover, this approach helps me discover new producers. Beaujolais is oft described as a dynamic wine region and that’s true, but on the other hand, there exists a swathe of subpar wines foisted on unsuspecting/undiscerning consumers, reinforcing negative impressions. Jean-Marc Lafont, Inter Beaujolais’ new president, told me that he is “interested” in these under-performers—after all, quality-driven producers can look after themselves. A few socks need pulling up.

Concrete eggs are increasingly popular alternative vessels to foudres and concrete vats. This row is installed at Louis-Claude Desvignes’ winery.

While significant strides in viticulture have allowed winemakers to exploit the potential of their land and ancient vines, there is work to do with respect to updating wineries. In particular, more producers would do well to invest in smaller fermentation vessels for more bespoke vinification and maturation. Plus, as a couple of winemakers pointed out, Beaujolais needs to enable longer élevage. Most bottle their wines before the following harvest because that is the accepted practice, or more often, because there is insufficient space in the winery. However, the best terroirs and cuvées would arguably benefit from a second winter in barrel, foudre or tank. That is a question of both space and money. Producers in Beaujolais can’t expect the same flood of income that is possible in neighbouring regions. Whereas a wine might sell for hundreds of euros in the most propitious parts of the Côte d’Or, here…well, a cherubic Chiroubles can cost just 31 euros.

Domaine du Romarand came to my attention in tastings for last year’s report, so this year, I paid my first visit to architect-turned-winemaker Anastasia Kritikou. She poses here in front of the original vertical wooden press that she still uses.

Yet, it cannot be denied that Beaujolais’s almost old-school mentality and aesthetic is part and parcel of its charm. Sure, you can install a hipster concrete egg or two without expelling those ancient foudres or concrete vats, now de rigueur. Step by step, Beaujolais is moving forward. Mindful of what is transpiring in some parts of the Côte d’Or, Beaujolais winemakers are aware of the pitfalls of hurtling forward too quickly and losing some soul in the process. I remember when, around 15 years ago, some entertained the idea of closer links with Burgundy, which was then rocketing to stardom. Nowadays, Beaujolais takes pride in its independence. It is proud of Gamay, and not to forget Chardonnay, which currently comprises 4% of vineyard land (some producers are aiming to triple that figure. Whereas carbonic maceration, full or semi, was synonymous with Nouveau and considered a kind of fermentation “shortcut,” it is now viewed as part of the region’s DNA—a technique that, again, distinguishes Beaujolais from Burgundy. Furthermore, Beaujolais is proud of its history, not least as the birthplace of low-intervention winemaking and the influential “Gang of Four.” It is a region rich with local culture and tradition, such as the decennial Les Conscrits celebrations.

Much of this has not translated to the broader market, and consequently, there are vestiges of prejudice against the region and its wines. Rock up with a delicious Morgon instead of a Morey-Saint-Denis and, sadly, some “connoisseurs” will look down their noses at you, ignorant that a few decades ago, the Beaujolais would have been as expensive as the Burgundy. Just the night before writing this, a 2019 Côte du Py was a revelation to seasoned oenophiles with no inkling that Beaujolais could achieve such heights.

It’s easy to convert people…They just have to drink the wine.

Côte du Py…Or Is It?

I usually update readers on the current issues surrounding Beaujolais, which in the past have included applications to the INAO for Premier Cru status by Fleurie and Brouilly. Unsurprisingly, given France’s notorious bureaucracy, there has been little progress in the intervening 12 months. I suspect the file was carried from one desk to another, but not much else. So, I advise reading my last report for details. Trust that I will update you when there is any movement, but don’t hold your breath.

As I mentioned before, if the application proves successful, it will leave Beaujolais’ most well-known and arguably most prestigious appellation, Morgon, without any Premier Cru vineyards. This would imply inferiority. Imagine if Vosne-Romanée had no Premier or Grand Crus. On the other hand, Pomerol’s châteaux have never been classified, and not only does it remain an esteemed appellation, but it avoided the imbroglio that has beleaguered Saint-Émilion.

This hill constitutes Côte du Py in Morgon, home to some of Beaujolais’ finest wines and a Premier Cru in all but name.

In recent months, some producers in Morgon have received unannounced visits from INAO inspectors. The INAO is clamping down on the alleged “misuse” of all six climat names, not least Côte du Py. Producers might claim that they have labelled their wines by climat since time immemorial and that this is how customers know their wines, however, the INAO is becoming more stringent. Essentially, they insist that only wines from vines located in the lieu-dit are permitted to use that name. Apparently, the INAO is considering Premier Cru recognition for vineyards that are 100% within the lieu-dit of the cadastral, 100% of the lieu-dit plus part of another, then also part or parts of lieux-dits. Even though authorities have not decided upon the criteria to be used, it is prudent to “tidy up” present labelling nomenclature.

The problem with somewhere like the Côte du Py is that there are plenty of wines labelled as such made from vines outside the titular lieu-dit. In fact, Côte du Py covers a much wider area and multifarious terroirs. To be honest, when Jean-Marc Burgaud showed me a map of the 250 hectares that winemakers can currently label as Côte du Py, I understood why the INAO decided to crack down. If new laws stipulate that the vines must come from the lieu-dit, those 250 hectares would shrink overnight to 59 hectares. Why now? Well, nothing has been said officially, but I speculate that this pre-empts any future application for Premier Cru status. Defined geographical boundaries reduce ambiguity, hopefully obviating objections that inevitably rise, like those that arose from Pouilly-Fuissé’s application.

The effect has been immediate. Jean-Marc Burgaud renamed his Morgon Corcelette to Morgon La Roche from the 2024 vintage onwards. I heard of instances where the INAO offered a grace period of one year, but domaines risk punitive fines if they continue to break the rules beyond then. Most will have no choice but to revert to the name of the lieu-dit, which might lack the cache and familiarity of “Côte du Py” (or others). Burgaud owns a considerable five hectares within the lieu-dit, so he will be relatively unaffected. There are options: Burgaud mentioned the possibility of blending lieux-dits together and inventing a “fantasy” name. I wonder whether customers will actually know the difference. As it stands, how many can rattle off all of Beaujolais’ village crus, let alone its multitude of lieux-dits? Though any transition period might disrupt producers and merchants alike, my view is that this clarification of vineyard sites will be positive in the long run. A great wine is a great wine however it’s labelled.

The Market

Though completely different, there are parallels between the wines of South Africa and Beaujolais. Both overdeliver. Both are underpriced. That does not pertain to every grower, of course, but these two regions are surfeit with great wines at prices suitable in more straitened times. This places them in a similar conundrum: Do you increase prices in order to gain respect and kudos, enable reinvestment into your winery, secure a livelihood for your family and tide yourself over during an inclement season? Or do you take note that overpricing your wine has long-term consequences that are currently bearing down on Bordeaux Grand Cru Classé, the Côte d’Or, California and Champagne and keep prices steady?

For Beaujolais producers, the answer is the latter. Again, much like their counterparts in the Cape, there is much less financial motivation than elsewhere. Winemaking is not simply a route to becoming a celebrity or a cult favourite. There is purity in their endeavour, which has been occasionally sacrificed in places where fetching high prices appears to be the ultimate aim. As such, this means that demand for Beaujolais is holding steady because restaurants can afford to list these wines and, crucially, customers actually order them. I guess it is up to the likes of myself to alter negative connotations towards Beaujolais.

Final Thoughts

I can bang on about Beaujolais ‘til the cows come home. The fact is, you have to drink it to believe it. You need firsthand experience with growers like Foillard, Viet, Godard, Lapierre, Desvignes, Thivin, Burgaud, Sunier, Dubois, Rottiers and so on. As consumers and restaurants tighten purse strings, Beaujolais is entering the conversation, being taken more seriously and nestling alongside classic wine regions (or even usurping Burgundy) on restaurant lists. Beaujolais is cool. It has a cache that slipped through Bordeaux’s fingers when the Bordelais were too busy looking for the next windfall. Some parts of Burgundy might not have learned from that mistake either.

At the same time, it is naïve to assume there is no stigma against the Beaujolais name. To some, it connotes Beaujolais Nouveau, a kind of unsophisticated alternative to Burgundy, not to be taken seriously…After all, DRC and Rousseau would never practice carbonic maceration, even though it is evident within the wines of some celebrated producers. Even Beaujolais Nouveau can be reinvented as a parochial, joyous celebration instead of something that once defined and tarnished the region. When you mention “BN” to its most celebrated growers, most see it as part of Beaujolais’ tradition. A modest Nouveau party every third Thursday in November is no bad thing.

There remains work to be done at the entry-level side of business, and this year’s tasting reconfirmed that there is too much substandard Gamay. The crucial difference is that, unlike in Burgundy, you are likely to pay very little for it. Upgrading to serious Beaujolais like that €31 Chiroubles is patently not going to break the bank, and the good news is that there are many Beaujolais wines just like it—more with each passing year.

Go buy some, try some, to misquote a great George Harrison song.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright,but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

But Seriously: Beaujolais 2021-2023, Neal Martin, April 2024

Cellar Favorite: 2014 M & C Lapierre Morgon Marcel Lapierre Cuvée MMXIV, Neal Martin, April 2024

Cellar Favorite: 1971 Hospices des Moulin-à-Vent Moulin-à-Vent, Neal Martin, November 2023

The Future Is Beaujolais: 2020-2022 Releases, Neal Martin, May 2023

Back For More Beaujolais, Neal Martin, August 2021

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Alex Foillard

- Annick Bachelet

- Anthony Thévenet

- Antoine Sunier

- Arnaud Combier

- Aurélie et Fabien Romany

- Cédric Vincent

- Château Bellevue

- Château Bonnet

- Château Cambon

- Château de Corcelles

- Château de Javernand

- Château de la Bottière

- Château de la Greffière

- Château de la Prat

- Château de la Terrière

- Château de Lavernette

- Château de l'Eclair

- Château de Poncié

- Château de Pougelon

- Château de Rougeon

- Château des Jacques

- Château des Moriers

- Château des Pertonnières

- Château des Ravatys

- Château des Tours

- Château du Durette

- Château du Moulin-à-Vent

- Château Grand'Grange

- Château Grange Cochard

- Château Thivin

- Cyril Coperet

- Domaine André Colonge et Fils

- Domaine Anita

- Domaine Anne-Sophie Dubois

- Domaine Azarra

- Domaine Baron de l'Ecluse

- Domaine Benjamin Passot

- Domaine Berthier

- Domaine Bertrand

- Domaine Calot

- Domaine Chevalier Métrat

- Domaine d'Argenson

- Domaine David-Beaupère

- Domaine de Bel-Air

- Domaine de Boischampt

- Domaine de Briante

- Domaine de Chênepierre

- Domaine de Colette/Jacky Gauthier

- Domaine de Colonat

- Domaine de Croifolie

- Domaine de Gry-Sablon

- Domaine de la Bêche

- Domaine de la Chaponne

- Domaine de la Croix des Charmes

- Domaine de la Grand'Cour/Jean-Louis Dutraive

- Domaine de la Grosse Pierre

- Domaine de la Laveuse

- Domaine de la Madone

- Domaine de la Pirolette

- Domaine de la Prébende

- Domaine de la Ronze

- Domaine de la Tour du Bief

- Domaine de la Voûte des Crozes

- Domaine de Rochegrès (Albert Bichot)

- Domaine de Roche-Guillon

- Domaine de Romarand

- Domaine des Braves

- Domaine des Chaffangeons

- Domaine des Gaudets

- Domaine des Maisons Neuves

- Domaine des Marrans

- Domaine des Nugues

- Domaine des Perelles

- Domaine des Roches du Py (Guénal Jambon)

- Domaine des Souchons

- Domaine du Chapitre

- Domaine du Crêt d'Oeillat

- Domaine du Penlois

- Domaine du Petit Pérou

- Domaine Dupeuble Père & Fils

- Domaine Dupré

- Domaine du Thulon

- Domaine du VieuxBourg

- Domaine Fontalognier

- Domaine Franck Chavy

- Domaine Gaget

- Domaine Gilles Coperet

- Domaine Gilles Paris

- Domaine Grégoire Hoppenot

- Domaine Joncy

- Domaine Julien & Sébastien Pacaud

- Domaine Labruyère

- Domaine Le Cotoyon

- Domaine Les Capéroles

- Domaine Les Garçons

- Domaine Les Roches Bleues

- Domaine Longère

- Domaine Mee Godard

- Domaine Oedipoda

- Domaine Passot Collonge

- Domaine Patrice Arnaud

- Domaine Perroud

- Domaine Perrusset

- Domaine Philippe Viet

- Domaine Raphaël Chopin

- Domaine Richard Rottiers

- Domaine Rochette

- Domaine Romanesca

- Domaine Ruet

- Domaine Saint-Cyr

- Domaine Striffling

- Domaine Thillardon

- Domaine Valma

- Domaine Zephyr

- Dominique et Rémy Passot

- D. Piron

- Emmanuel Follet

- Famille Chasselay

- Famille Coperet

- Famille Dutraive

- Famille Gauthier

- Famille Girin

- Famille Mélinon

- Famille Morin

- Famille Sornay

- Frédéric Berne

- Frédéric Sornin

- Georges Descombes

- Georges Duboeuf

- Jean Foillard

- Jean-Marc Burgaud

- Jean-Michel Dupré

- Jean-Paul Brun

- JF Pegaz

- Jules Metras

- Julien Sunier

- Laurent Gauthier

- Les Souriants

- Les Vignes de l'Imprévu

- Louis-Claude Desvignes

- Lucas Dutraive

- Lucien Lardy

- Ludovic Montginot

- Maison Le Nid

- Marcel Lapierre

- Mélanie et Daniel Bouland

- Nicolas Boudeau

- Nicole & Romain Chanrion

- Olivier & Alexis Depardon

- Olivier Pezenneau

- Pascal Aufranc

- Patrick Tranchand

- Pauline Passot

- P. Ferraud & Fils

- Pierre-André Dumas

- Pierre-Marie Chermette

- Robert Perroud

- Sandrine Henriot

- Sébastien Besson

- Steeve Charvet

- Sylvain Martel

- Terre Rouge Vignes et Vins

- Thibault Ducroux

- Thierry Janin

- Thomas Collonge

- Trenel

- Vignobles Jambon

- Yohan Lardy