Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

2025 Champagne:New Releases (Updated Dec 2025)

BY ANTONIO GALLONI | APRIL 8, 2025

Additions - December 30, 2025:

A. Bergère, A. Margaine, A. R. Lenoble, Adrien Renoir, Alexandre Bonnet, Alfred Gratien, Aubry, Barbichon & Fils, Barons de Rothschild, Benoît Marguet, Bertrand-Delespierre, Besserat de Bellefon, Boizel, Brimoncourt, Castelnau, Cattier, Charpentier, Christophe Baron, Clos Beau Site, Crété Chamberlin, Daniel Moreau, De Saint Gall, Dehours & Fils, Devaux, Dhondt-Grellet, Diebolt-Vallois, Domaine Hélène, Domaine Vincey, Dominique Cousin, Doyard, Drappier, Duval-Leroy, Elise Godin, Emeline de Sloovere, Eric Rodez, Famille Moussé, Fleury, Forget-Brimont, Franck Bonville, Gaiffe-Brun, Gamet, Gaston Chiquet, Georges Vesselle, Girard-Bonnet, Gonet-Médeville, Guy Larmandier, H. Billiot Fils, H. Goutorbe, Jacquart, J.L. Vergnon, Jérome Blin, Jules Brochet, La Rogerie, Lafalise-Froissart, Lamiable, Lancelot Pienne, Lanson, Leclerc Briant, Legras & Haas, Lelarge-Pugeot, Louise Brison, M.G. Heucq, Madame S, Madeleine Brochet, Mailly, Marc Hébrart, Marie Tassin, Matthieu Godmé-Guillaume, Michel Arnould, Michel Gonet, Nicolas Maillart, Odyssée 319, Palmer & Co., Pascal Henin, Payelle Pére & Fils, Pehu-Simonet, Perrier-Jouët, Pertois-Lebrun, Pierre Baillette, Pierre Gimonnet & Fils, Pierre Paillard, Piper-Heidsieck, R. Pouillon & Fils, Rémi Leroy, Rene Geoffroy, Roger Coulon, Savart, Tarlant, Telmont, Thierry Fournier, Ullens, Valentin Leflaive, Vilmart & Cie, Waris Hubert, Wirth Michel

My annual March trip to Champagne is always one the highlights ofthe year. Many producers are preparing to launch their new releases. At the largerhouses, this is the time when winemakers are finalizing their blends and deciding whether or not they are going to bottle their tête de cuvées. With spring around thecorner, thoughts start to turn to the young vintage and what it might bring.

This year, things were different. Very different. Deepconcern over the global economy and the United States’ tariff policies, nowinstated, cast a pall on every tasting. With the experience of 2020, someproducers had already sent a significant portion of their projected 2025 salesvolume to the U.S. Even so, the mood was distinctly subdued. That’s a shame,because Champagne continues to be one of the most dynamic regions in the world.

Jérôme Prévost contemplating the state of the world in betweenwines.

The Grandes Marques – The Changing of the Guard

One of the biggest trends in recent years in Champagne hasbeen the reawakening of the grandes marques following a period in which growerChampagnes gained massively in prominence with professional buyers andconsumers alike. The sheer number of growers multiplied by the many wines theyeach make, along with the flat number of grand marques, led to a situationwhere grower Champagnes vastly dominate over large houses in terms of the sheeramount of real estate they command on restaurant lists, still the most covetedof placements. This has not gone unnoticed.

One of the first grandes marques to reinvent itself wasRoederer, as I have written in many previous articles. Roederer’s push intoorganic and then biodynamic farming was not only innovative, but it alsoinspired other producers to do the same. Under the leadership of longtime Chefde Caves Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, Roederer has become the largest farmer ofbiodynamic vineyards in Champagne. The flagship Cristal and Cristal Rosé areamong the most contemporary Champagnes, while a bevy of new wines haveincreased the offerings considerably.

Krug Chef de Caves Julie Cavil, flanked by tastingcommittee members Isabelle Bui and Jérôme Jacoillot at Krug’s new winemakingfacility in Ambonnay.

The younger generation is following suit. At Dom Pérignon,Chef de Caves Vincent Chaperon once again presented a range of vins clairsto start the tasting, each accompanied by detailed maps of the correspondingplots. Last year, I toured several vineyard sites with the entire viticulturalteam. Chef de Caves Richard Geoffroy, Chaperon’s predecessor and mentor, rarelyshowed vins clairs. I don’t remember him ever mentioning a vineyard inall the years I tasted with him. Not once. That is not a criticism, it’s simplya reflection of how different generations of Chefs de Caves think about theirroles. Chaperon has also decided to start bottling Dom Perignon in years wherequality is high but volumes are low because he wants to document each vintage.That is another departure from the past. The 2017 Dom Pérignon, the lastvintage vinified by Geoffroy, will be a tiny release that is projected to lastin the market for just a few months. It is the smallest production ever for Dom Pérignon. Chaperon has bottled Dom Pérignon in everyvintage from 2018 to 2024, except for 2023. More importantly, there is a newfeeling of energy at Dom Pérignon today that is palpable.

At Krug, Chef de Caves Julie Cavil has added youngercolleagues to her tasting committee with the goal of canvassing the views ofseveral expert tasters. The new Krug winery in Ambonnay is a major step up fromthe cramped quarters in Reims and a bold investment for the future. This year,Krug introduces a Clos d’Ambonnay Rosé, the first wine they have added to theirrange in about 20 years, since the release of the 1995 Clos d’Ambonnay.

In Reims, Ruinart recently opened a gorgeous hospitalityfacility where guests can taste without an appointment and purchase a selectionof Champagnes along with other items. In addition to their own Champagnes, Ruinartpours wines from two grower domaines in a rotating selection to enhance theguest experience at their tasting bar. The idea that a grande marque, or anywinery for that matter, would show other producers’ wines alongside their ownin their hospitality center shows both tremendous yet understatedconfidence and an openness to the world that is so refreshing. The previousgeneration of Chefs de Caves only concerned themselves with grande marqueChampagne, and in some cases, with their wines only. This new vision reflectsthe contemporary attitude that Chef de Caves Frédéric Panaïotis has brought toRuinart. It’s hardly a surprise Panaïotis is making some of the most excitingwines in Champagne today.

Tasting vins clairs at Selosse, where wines oftenapproach the texture and weight of still wines in other regions.

Growers on the Move

On the grower front, the proliferation of young domainescontinues to be nearly impossible to keep up with. That makes Champagne one ofthe most vibrant regions in the world. Many of the established grower domaineshave now passed or are in the process of passing to the next generation. From apure wine standpoint, grower Champagne continues to shine light on thepotential of specific vineyard sites and micro-regions. This is even more trueof areas that have historically been regarded as less important, that have beencontracted out to larger houses, or where there have never been many benchmarkdomaines or wines to evaluate in the first place. Growers continue toexperiment with some of the more obscure permitted varieties to creates newwines, the best of which are compelling. Various offshoots of sustainablefarming continue to gain traction, including holistic concepts that encouragehealthy and vibrant ecosystems beyond just the vine, such as regenerativefarming and vitoforestry, where trees are planted within vineyards.

From a practical standpoint, grower domaines often strugglefrom being small and subscale. The administrative and bureaucratic requirementsthat are imposed on wineries today are especially daunting for smaller,family-run estates. Moreover, purchasing land and achieving growth areincreasingly difficult. Last but certainly not least are issues aroundinheritance taxes, which in France are especially punishing. Pretty much everygrower domaine would like to make and sell more wine.

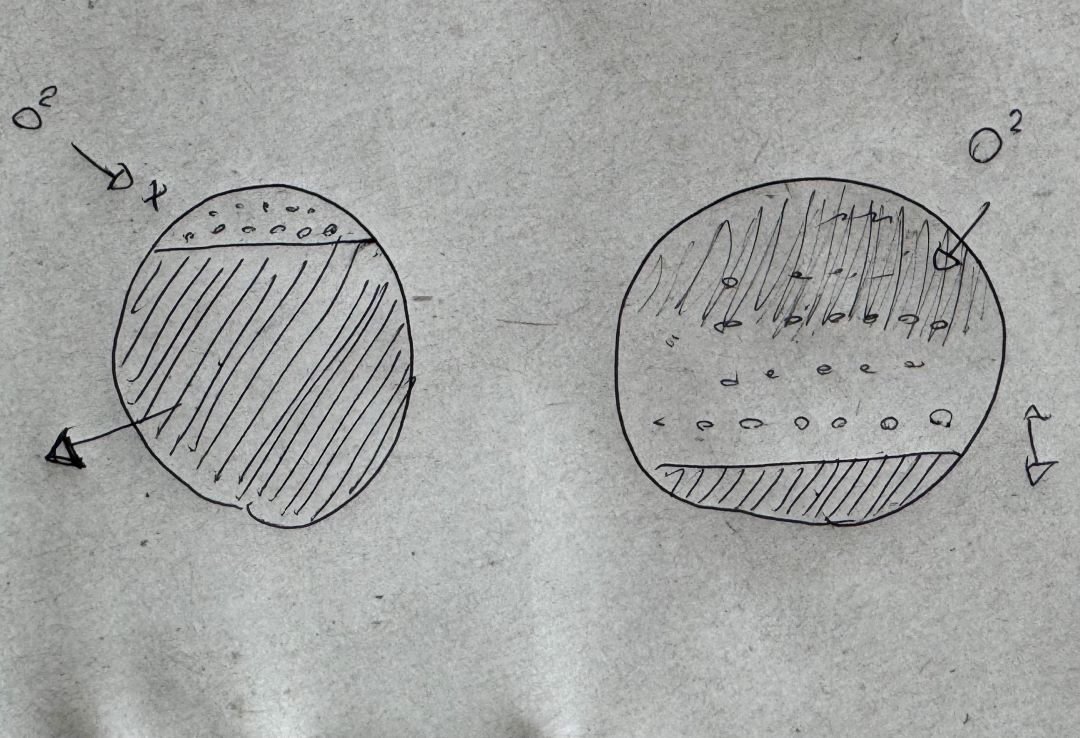

Alexandre Chartogne’s framework for Champagne divideswines into those that are composed of mostly mineral matter (left) and thosethat are predominantly organic (right) and are therefore more vulnerable todecomposition. Mineral wines are vinified and aged with minimal oxygenation.The goal is to preserve that mineral character. Chartogne believes that organicwines are less interesting and more likely to age relatively quickly. His goalis to transform some of their organic matter to mineral though gentle oxidationduring élevage. As a result,these wines (the Meuniers, for example) see more oxygen during their time in barrel.

2024: First Thoughts

Tasting vins clairs is a very good way to get an ideaof the new vintage, especially in a challenging year like 2024 where sectorsexperienced widely different conditions. That said, I have found thatextrapolating these tastings into an idea of what the finished Champagnes will belike to be a tenuous exercise at best because so much takes place with blendingand long aging on the lees, when the young wines transform into Champagne.Moreover, producers only show a small selection of their base wines, and theseare naturally going to be the best in the cellar. Nevertheless, I never miss anopportunity to taste vins clairs, as these tastings are highlyeducational.

In 2024, the main theme was rain, rain and more rain. Averagerainfall during the growing season was around 700 mm. Some regions saw close todouble that. Mildew was a constant threat throughout the year. The mostdramatic period was around September 23 and 24, in which as much as 80 mm of rain fellin two days. Naturally, well-draining sites, such as those on chalk, werefavored. The northern Montagne de Reims, which includes Mailly, Verzy andVerzenay, saw considerably less rain than the southern Montagne de Reims.

“The clear winner of the year is Meunier because of itsshort vegetative cycle, which adapted well to the conditions of 2024” Chef deCaves Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon explained at Roederer. “We used 30% Meunier inthe Collection, the most ever.” Lécaillon bottled both Cristal and Cristal Rosé.“We essentially had a window of ten days of favorable weather to pickeverything. Before then, it was not ripe, and after, it rained,” Chef de CavesVincent Chaperon explained at Dom Pérignon. “It all comes down to the capacityof sites to drain, as was the case in the northern Montagne de Reims and well-drainingsites in Aÿ, which did better than Bouzy, for example. We are less happy withour Meuniers.”

Innovation is a constant theme at Henri Giraud. Barrelson the top row of this image were built with sandstone heads.

“It was extremely difficult in the vineyard,” Chef de CavesJulie Cavil explained at Krug. “Between mildew and yields that were down closeto 50%, we really struggled in the vineyard. This is the widest range we haveever seen between what we experienced in the vineyard and then what we sawlater in the wines.”

For 2024, the maximum permitted yield in Champagne was10,000 kilos per hectare, a touch lower than in previous years because oflighter demand in global markets. Most producers reported yields down 40-50%from that number. There are some exceptions. Father-and-son teamLaurent and Thomas Champs reported a full crop at Vilmart. Even with lower yields, most Chef de Caves I spoke at the larger houses bottled their tête de cuvées. I tasted only a fewsamples from the Aube, which was hit especially hard with a devastatingcombination of frost, hail and rain that lowered production to virtuallynothing in the most affected areas.

Tasting vins clairs with Vincent Laval at the new barrelcellar just a few steps away from the old cellar, which is now used for aging.

2022: A Step Forward

This year, readers will start to see the first non-vintageChampagnes based on 2022. I have been critical in the past of some recent drier vintages, such as 2015 and 2020, where so many wines are markedby a pronounced vegetal character. I am happy to report that, so far, I do notsee those issues in the 2022-based wines so far, despite considerable heat stress in certain sectors.

For further context, by now it is no secret that Champagnehas struggled in some warmer years with wines that often show a vegetalcharacter that suggests underripe fruit. This is one of the modern dilemmas inChampagne. When I asked producers about this in their young 2015s, most of themeither pushed back or were not very happy to hear my comments. But time is thegreat equalizer. And over time, it became clear that many 2015s indeed had avegetal character. A few years later, vintage 2020 offered a sort of replay,except by then, producers had more widely accepted the idea that warmvintages might be more challenging than they seemed initially. Research is underwayto understand if these issues are related to a mismatch of sugar versusphenolic ripeness or perhaps to the appearance of certain kinds of mushrooms. Itend to think it is more a question of the former. One thing is certain:Choosing harvest dates in Champagne in the past was almost always done usingtechnical lab data. In other regions, top winemakers know that, while technicaldata may offer support, the best way to know when to harvest is by tasteanalysis. This approach has been slower to arrive in Champagne but now seems tobe more widely used. Perhaps that explains the relative success of 2022. I amcurious to taste more wines as they arrive onto the market.

Coda: Vintage 2022 – Latest Thoughts as of November 2025

I have had an opportunity to taste many more 2022-base Champagnes since the main body of this report was published in April 2025. I am happy to report that many of the 2022-base Champagnes are gorgeous, especially considering the challenges some growers faced in achieving full ripeness in recent years, such as 2015 and 2020. It’s much too soon to know how 2022 will present in vintage Champagnes and têtes de cuvée. For now, the generous, radiant style of the year seems especially well suited to entry-level and NV bottlings, where an extra kick of textural richness makes the wines so easy to drink and enjoy. Perhaps even more importantly, so far I don’t see the worrisome vegetal notes that characterized so many 2015- and 2020-based NV and vintage Champagnes.

These two 2017s from Pierre Péters say it all when itcomes to how different sites respond to challenging weather, in this case,late-season rains. Chétillons, with its chalky soils, was clearlyfavored over Montjolys, where clay-based soils are more water-retentive.

On Disgorgement Dates

Listing disgorgement dates, base vintages and other technical information has long been our practice. Younger readers may not remember the time, not too long ago, when NV Champagne labels provided the consumer with very little, if any, information about the wines. Champagne was labeled like Coca-Cola. It’s still that way for the most industrial Champagnes. The average person had no way to tell one year’s release from any other release of the same wine. Reviewing these wines critically was highly problematic, as there was no way for consumers to know if they were buying the wine that was actually reviewed.

Along the way, producers and importers began listing disgorgement dates. Growers led the way. This was the first step in differentiating releases. Large houses were initially very resistant. Many grande marque CEOs and Estate Managers flat-out told me they refused to provide this information. “Our clients don’t care about this,” the head of one of Champagne’s most exclusive houses told me. My response was simple. I would not review wines that did not provide some sort of basic information for the consumer. That did not apply just to grower wines or NV Champagnes, it also included iconic wines like Krug’s Grande Cuvée and Laurent-Perrier’s Grand Siècle.

Over time, Champagne producers became more sophisticated. Many of them, again led by growers, began to provide even more information, including base vintage, blends, dosage levels and other details. Krug adopted the Edition series for their Grande Cuvée. For the first time, Grande Cuvée became an allocated Champagne, a far cry from the days when Krug struggled to sell their production. This was not that long ago. Krug IDs on back labels appeared a short time later, providing consumers with more information than ever before. Laurent-Perrier followed with Iterations for their Grand Siècle. Roederer introduced back labels with codes and then created the new numbered Collection series when they phased out the Brut Premier bottling. Occasionally, I would hear complaints, mostly from the wine trade and producers, specifically that buyers only wanted the specific disgorgement I had reviewed. That struck me as a bit hard to believe, given that most houses, even smaller domaines, are disgorging throughout the year.

This brings us to the present. Champagne, especially at the grower level, remains a hot to very hot category. Vinous has readers in more than 100 countries around the world, split evenly between the United States and the rest of the world. Obviously, I taste one disgorgement of each wine, but many disgorgements enter the market. Readers should expect wines disgorged within the same calendar year to be materially similar. For that reason, reviews may now indicate that wines are disgorged throughout the year. Lastly, while disgorgement dates are important—mostly as a differentiator of various releases—the more critical piece of information is the base vintage. That’s what I would like to see on more labels.

About this Article

I tasted all the wines in this report during aweek in Champagne in March 2025, with follow-up tastings in New York in November and December 2025. Anne Krebiehl MW contributed additional reviews.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Vinous Icons: Roederer – Four Decades of Cristal & Cristal Rosé, Antonio Galloni, November 2024

Champagne: The 2024 Spring Preview and Fall Additions, Antonio Galloni, March 2024

Champagne: 2023 New Releases, Antonio Galloni, November 2023

The 2022 Champagne New Releases, Antonio Galloni, May 2022

Champagne: 2021 New Releases, Antonio Galloni, November 2021

2016 Champagne: Harvest Report, Antonio Galloni, April 2017

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- A. Bergère

- Adrien Renoir

- Alexandre Bonnet

- Alexandre Lamblot

- Alfred Gratien

- A. Margaine

- Antoine Chevalier

- A. R. Lenoble

- Aubry

- Ayala

- Barbichon & Fils

- Barons de Rothschild

- Benoît Déhu

- Benoît Marguet

- Bérêche et Fils

- Bertrand-Delespierre

- Besserat de Bellefon

- Billecart-Salmon

- Boizel

- Bollinger

- Brimoncourt

- Castelnau

- Cattier

- Cazé-Thibaut

- Cédric Bouchard-Roses de Jeanne

- Charles Heidsieck

- Charpentier

- Chartogne-Taillet

- Christophe Baron

- Christophe Baron

- Christophe Mignon

- Clandestin

- Clos Beau Site

- Crété Chamberlin

- Daniel Moreau

- Dehours & Fils

- Delamotte

- De Saint Gall

- Deutz

- Devaux

- Dhondt-Grellet

- Diebolt-Vallois

- Domaine Hélène

- Domaine Les Monts Fournois

- Domaine Vincey

- Dominique Cousin

- Dom Pérignon

- Doyard

- Drappier

- Duval-Leroy

- Elise Godin

- Emeline de Sloovere

- Eric Rodez

- Famille Moussé

- Fleur de Miraval

- Fleury

- Forget-Brimont

- Francis Boulard & Fille

- Franck Bonville

- Gaiffe-Brun

- Gamet

- Gaspard Brochet

- Gaston Chiquet

- Gatinois

- Georges Laval

- Georges Vesselle

- Girard-Bonnet

- Gonet-Médeville

- Guiborat

- Guillaume S.

- Guy Larmandier

- H. Billiot Fils

- Henri Giraud

- H. Goutorbe

- Jacquart

- Jacques Selosse

- Jacquesson

- Jérome Blin

- Jérôme Prévost - La Closerie

- J. Lassalle

- J.L. Vergnon

- Jules Brochet

- Krug

- Lafalise-Froissart

- La Grande Dame

- Laherte Frères

- Lamiable

- Lancelot Pienne

- Lanson

- Larmandier-Bernier

- La Rogerie

- Laurent Perrier

- Leclerc Briant

- Legrand-Latour

- Legras & Haas

- Lelarge-Pugeot

- Louise Brison

- Madame S

- Madeleine Brochet

- Mailly

- Marc Hébrart

- Marie Courtin

- Marie Tassin

- Matthieu Godmé-Guillaume

- M.G. Heucq

- Michel Arnould

- Michel Gonet

- Moutard

- Mouzon-Leroux

- Nicolas Maillart

- Odyssée 319

- Palmer & Co.

- Pascal Agrapart

- Pascal Henin

- Paul Bara

- Pauline Collin Bérêche

- Payelle Pére & Fils

- Pehu-Simonet

- Perrier-Jouët

- Pertois-Lebrun

- Philipponnat

- Pierre Baillette

- Pierre Gimonnet & Fils

- Pierre Moncuit

- Pierre Paillard

- Pierre Péters

- Piper-Heidsieck

- Pol Roger

- Rémi Leroy

- Rene Geoffroy

- R. H. Coutier

- Roederer

- Roger Coulon

- R. Pouillon & Fils

- Ruinart

- Salon

- Savart

- Taittinger

- Tarlant

- Tellier

- Telmont

- Thierry Fournier

- Ullens

- Valentin Leflaive

- Veuve Fourny & Fils

- Vilmart & Cie

- Vincent Cuillier

- Vincent Laval

- Waris Hubert

- Wirth Michel