Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Friuli-Venezia Giulia: In Search of an Identity Part II

All Eyes on Orange

BY LAURA BRUNO | OCTOBER 02, 2024

Macerated white wines were at the forefront of my mind on the way to Friuli.

I was fascinated by the production method, seemingly rich history and personalities behind their execution. To my knowledge, these were the defining wines of Friuli-Venezia Giulia—cult classics characterized by their idiosyncratic style and exclusivity. I championed macerated wines in the early stages of my career. I preached to guests and colleagues the historical significance of making white wine as it always used to be.

A

handmade sign straddling the Italian/Slovenia border advertises an “Orange Wine

Tasting".

I would acknowledge but discount claims of flawed production in the name of 'rock and roll': if you don't like it, you don't get it. My passion for the wines fueled my excitement to visit what I saw as the mecca of their production. No less than a day into my travels, I learned that macerated white wine from Friuli had a much different story than the one I’d been told and had been retelling. What I thought was a tale of history and tradition is actually one of art, accident and masterful marketing.

The hype surrounding macerated wines from Friuli has created some of the tension plaguing the producers I wrote about in my last piece, Friuli Venezia-Giulia: In Search of an Identity. As the dust settles around orange wine and its producers in Friuli are still riding a high, we should have an objective conversation about the inception and production of the style that has unintentionally become the face of Friuli and the darling of the natural wine world.

Overhead

view of the rolling hills of Oslavia within Collio.

Modern Day: Oslavia

Friuli-Venezia Giulia is a patchwork of cultures and traditions fragmented by a war-torn past. Oslavia, a non-governmentally recognized village in the eastern foothills of Collio, is a Slovenian enclave. Fewer than 200 people call Oslavia home, yet it is the epicenter of macerated white wine production. The area has a clear, unapologetic tie to Slovenia despite residing entirely on the Italian side of the border.

The terroir in Oslavia is similar to the rest of Collio. The area has Ponca soils (a mix of marl and sandstone), sees intense rainfall, and is directly influenced by the Mediterranean Sea and the nearby Alps. In contrast to the rest of Collio, Oslavia has a notably windy microclimate and topography that mimics an amphitheater. The air feels different in Oslavia than in the rest of Collio. It is the most culturally aligned area I have visited throughout my trip. That alignment extends beyond culture and into wine production.

Within Oslavia, a group of recognizable producers has formed a society aptly named the Associazione Produttori Ribolla di Oslavia, a collection of seven wineries dedicating either all or a significant portion of their production to the preservation of Ribolla Gialla through maceration. In contrast to the rest of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the association has a singular mission, aligned values, a champion grape and a concise identity. Not all, but many of the major players in the orange wine movement are members of this association. Blockbuster producers such as Radikon, Fiegl, Prinčič and Gravner are active. Major non-member producers like Damijan and Franco Terpin also focus on similar vinification.

A halo

hanging over fermenters at Damijan.

The group loves Ribolla Gialla and bonds over a shared perspective that maceration is key to best expressing the varietal. Outside of Oslavia, many disdain the grape. It can be difficult to ripen and can lack character. Ribolla has fallen further out of favor due to high-yielding plantings in the lowland plains, where Ribolla Gialla production has been watered down to fuel demand for cheap bubbles. Producers in Oslavia dismiss the grape’s floundering reputation, instead championing the variety as significant and speaking passionately about their work. They see their plantings as an act of historical preservation. They believe the grape’s misrepresentation comes from a mismatch of terroir. Producers in Oslavia feel that their township’s unique composition of Ponca soils is a superior landscape, providing ideal conditions for bringing Ribolla Gialla to life.

The mission sounds incredible: a Slavic minority fighting within a larger wine-producing region to solidify Ribolla Gialla's dominance as an essential and precious indigenous variety. It’s a noble cause pursued through even more noble means: embracing the ‘ancient’ winemaking technique of maceration.

Through the adoption and implementation of maceration, producers capture precisely what the rest of Friuli is missing: a shared identity. While there is drastic variation in style from producer to producer, the shared ethos of production acts like a binding thread. Achieving this strength of identity is complex. Direction and focus can take centuries to forge. Imagine my surprise when I learned macerated wines in Oslavia do not have a long, hallowed history. In fact, the “legendary” producers of the category all have a relatively brief timeline of macerating and focusing on Ribolla. This whole practice was something of an overnight sensation, starting just 28 years ago in 1996.

Polyculture is at play in the vineyards at the Gravner Estate.

What Happened in 1996?

"Josko Gravner made the best white wines in all of Italy…before he started macerating." – a sentiment many winemakers expressed during my visit.

Despite belonging to the Slavic minority, Josko Gravner was the face of the Italian side of Collio—garnering praise from winemakers regardless of ethnicity. Gravner was one of Italy's most influential wine producers throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and he was holistically beneficial for Friuli-Venezia Giulia. He achieved mass acclaim for his whites after introducing the use of barrique in fermentation and aging. Gravner’s success also correlated with a movement toward more sanitary vinicultural practices, which created an opportunity for the region to be taken seriously for its production, establishing its role in the larger scheme of Italian wine.

That all changed in 1996 when torrential rains wiped out 95% of Gravner's and the surrounding wineries’ production in Oslavia. He was left with virtually no fruit. Carrying a reputation taller than the Alps at the backdrop of his estate, Gravner had a decision to make. Poor vintages and unexpected weather threats always loom over wineries. When crops are damaged, harmed or completely lost, these circumstances necessitate difficult choices. Gravner could have purchased fruit from other wineries outside of Oslavia to supplement his loss, but he did not. Instead, he chose to work with the crop that nature offered despite its flaws. He tried macerating his white wines with barely any fruit to work with. Innovation is often born from necessity.

The shift in Gravner's production had radical repercussions. A winemaker once heralded for his lush, rich, barrique-aged whites had produced an acidic, cloudy, challenging wine. With Gravner's status in the area, other producers of the shared Slavic minority followed suit, macerating their equally diminished crop, done simply out of belief in Gravner.

A single

chair in a sea of amphorae at Gravner.

Upon release, the 1996 vintage was poorly received in Italy. Gravner's reputation for white wine was shattered. Over the next handful of vintages, Gravner and many producers in Oslavia continued to experience less-than-ideal growing conditions. He and others pursued maceration to make the best of low yields. Gravner would, in the coming years, take a trip to Georgia, where he became enchanted by amphorae. Inspired, Gravner and his counterparts in Oslavia began experimenting. Despite their efforts, the wines spiraled into relative obscurity in the early 2000s. That script would flip in 2005 when famed wine writer Eric Asimov from The New York Times visited the region. His praise for the novelty of Gravner's production lit a spark that would skyrocket interest globally for the niche wines.

Asimov, in his article “New Wine in Really Old Bottles”, writes:

"But he was not satisfied making wines like everybody else. Mr. Gravner began to experiment with techniques considered radical by the winemaking establishment. The hazy, ciderish hue of the resulting white wines, so different from the usual clear yellow-gold, persuaded some that the wines were spoiled. But one taste showed they were fresh and alive, with a sheer, lip-smacking texture."

Just like that, Gravner was a star again.

The piece created an undeniable buzz. Asimov praised Gravner and his contemporaries for being natural, singular and visionary. The article was published at a time when Gravner’s wines were misunderstood by his Italian colleagues. Now Friuli had a new spotlight, still pointed at Josko Gravner, and including the cohort of winemakers following in his footsteps.

The wines garnered immediate attention in the United States, especially within sommelier circles, and Gravner began exporting his wines, increasing visibility in major markets. The popularity of other macerated producers skyrocketed as well. Radikon, Damijan and others enjoyed more attention in the press, which improved business. The popularity of the wines outside of Italy gave credence to a style rejected within Italy. Production continued, and soon, these macerated wines became some of the most sought-after in the world. Without conjecture, the popularity of Josko Gravner and others in Oslavia sparked a movement for skin contact production around the globe. Gaining inspiration from generations of production in Georgia, Gravner was not the first to macerate in amphorae, but he became the poster child of maceration, amphorae and natural wine.

The timing of Asimov's article was auspicious. While the industry in Italy criticized the wines for their apparent technical flaws, their “natural” energy enchanted other major global markets. In the early 2000s, environmental consciousness was a major driving force for consumers, particularly in the United States. Concerns over climate change, farming practices and humanity's impact on the planet were at the forefront of many progressive minds. As a result, wine lovers were increasingly drawn to “natural” or “low intervention” wines, even if it came at the cost of taste.

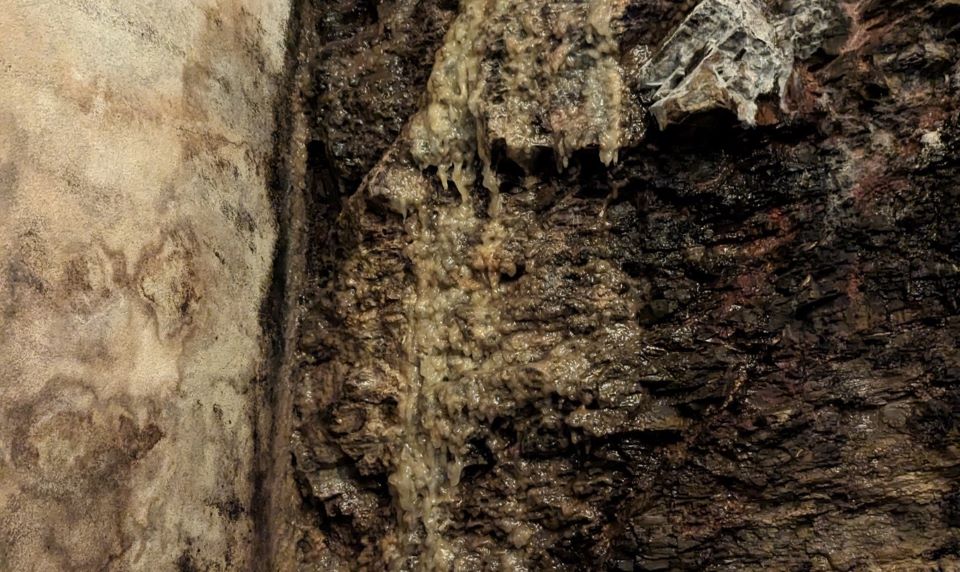

Stalagtites

form on a moist wall of Ponca at Radikon.

Afterglow or Aftermath

The ability and willingness of Oslavian producers to band together around the shared success and acclaim of this wine style is a masterclass in marketing and commercialization. In 2010, they swiftly formed the Associazione Produttori Ribolla di Oslavia. The wineries worked in tandem, preaching a collective identity while producing wildly different expressions of macerated Ribolla Gialla. The group toes a line between appearing as mavericks and wise old owls. The messaging is clear and loud—so loud that, to many, Friuli is associated solely with orange wine production despite its relatively minimal presence.

Today, the macerated movement in Friuli is certainly not without criticism. The process of maceration results in difficult wines that many dislike and regard as flawed. But even more concerning than the wines' quality is the shadow their popularity casts over the rest of the region. A roaring success born from a freak storm has now created a confusing landscape in Friuli. Many non-macerating producers recognize this confusion as a net negative on the region's ability to establish identity. A common sentiment I heard was that macerated wines made in Friuli, and more specifically Oslavia, were not representative of the land but more representative of the men who made them. Neighboring critics believe that maceration masks terroir to the point of vanishing, washing away a sense of place in pursuit of personality or perhaps even ego.

Wines that speak nothing of their origin are not an ideal face for a region in an identity crisis.

While tasting, I considered the sentiment of the non-macerating producers. Are the wines devoid of terroir? I investigated whether the criticism was justified or an extension of cultural alienation and/or jealousy.

The gracious tasting lineup from Radikon.

Tasting the Wines

I had multiple opportunities to taste macerated wines throughout my trip. As previously mentioned, I have long championed the category, even in the face of glaring technical flaws. Issues such as volatile acidity, oxidation and Brettanomyces are common and, in most cases, define the wines. These characteristics can be hard to swallow and become even more difficult to appreciate when coupled with tannin and phenolics from skin contact. Some producers embrace these flaws, and some work tirelessly to minimize them. My experience with macerated wines is not as monotone as many would assume.

Damijan

The trek to the Damijan estate was long and rugged. After a bumpy car ride through the forest, a stunning ultramodern estate emerged on top of a hill. The winery sits on what was an old battlefield. Halo-shaped and architecturally breathtaking—it was so pristine that it looked like no one had ever stepped inside. Tamara Podversic, Damijan’s daughter, walked me from barrel to barrel and spoke with a deep fascination about the winemaking process. She noted that the vines would determine the crop and that her control and influence could only extend to the operations in the winery. This comment starkly contrasted my conversations with non-macerating producers, many of whom took a more authoritarian approach to vineyard management.

We tasted directly from the barrel for our entire tour. I shared Tamara Podversic’s fascination. The general style at Damijan is to produce bottlings with deep aromatic intensity. Some varieties did not take to maceration with grace; others reached new heights of expression. The 2017 Ribolla Gialla was the standout. The wine has an evident influence from botrytis. The nose conjures Sauternes: crystalized honey, saffron and freshly grated ginger mingling around a core of orange citrus and stone fruit. The texture is full. I caught myself almost chewing on the wine. The palate has substantial bitterness and grip, as expected and anticipated with macerated whites. Acidity is present, mainly in the form of controlled volatility. The wine is not racy or refreshing, but borderline satiating. Its weight impacted me both physically and mentally. Like other wines in Friuli, the Ribolla Gialla has glaringly elevated alcohol—a quality some drinkers might find distracting. The wine feels like a large bass drum being struck with expert timing at a low BPM. Consistent in its depth and tone. Vibrating with every hit. It's a beautiful baritone wine.

Other bottlings of interest included 2020 Kaplija, a blend of Chardonnay, Friulano and Malvasia. Kaplija has the most acidity and is the most balanced wine of the bunch. It is the only wine at Damijan that could join a dinner table to enhance food, not overshadow it.

Lastly, their 2021 Pinot Grigio is an unexpected treat. A surprising hue of magenta struck me right between the eyes as it funneled through the barrel into my glass. The wine is less serious than the others we tried. I relaxed with this juicy, friendly offering. However, it does not shy away from tannin or volatile acidity and is worth seeking out.

Martin

Fiegl, President of the Associazione Produttori Ribolla di Oslavia, shows the

township's unique terroir.

Gravner

The Gravner estate, similar to Damijan, looks like a museum. Everything is artfully placed and displayed. I feared one wrong step would disrupt the methodical layout. Words at Gravner were few and far between. The estate offered a tour and tasting but declined to answer the questions I had prepared for them. I was guided by Gravner’s daughter Mateja from the vineyard to the winery. There was an increased focus on their land, which I had anticipated. Mateja Gravner said her father’s continued production of skin-contact whites fermented in amphorae was in pursuit of stripping the wine down to highlight vineyard practices. The land is picturesque. Biodiversity abounds, with polyculture influencing each plot. Ponds, flowers, various crops and birds cohabitate with the vines, creating a unique and rare ecosystem.

Harshly juxtaposed with the vineyard's colorful, fantasy-like appearance is the winery. The main portion of the facility is deep in the moist, cold earth. The winemaking area is simply a rustic room housing amphorae. In the middle of the space sits a single wooden chair, which, if radiocarbon-dated, may be the oldest chair in history. The contrast between a lively, budding vineyard and a stark, dungeonesque winery was not lost on me. This was Gravner’s point of transcendence. The earth dictated his wines, minimizing the intervention of man.

The winery produces very few wines, and its catalog is set to become even smaller as Gravner and his daughter narrow their production exclusively to Ribolla Gialla and Pignolo. How does the unique production approach manifest in the glass? Do the wines reflect the vineyard's liveliness or the winery's austerity?

We tasted two vintages of Ribolla Gialla: 2020 and 2017. The wine is tightly wound and buttoned up. Its distinctive amber hue makes it eye candy in the glass. Fruit is present on the nose but not in traditional form. Here, golden apples, bitter oranges and white peaches are crunchy but oxidized and bruised. Savory, dried herbs—rosemary and thyme—play an essential role, along with a hint of mild, wild marigolds. The wine smells yeasty, slightly lactic and has noticeable volatile acidity. The palate is refreshing at first, then bracing and lastly, grippy. It is like experiencing three wines all at once. Similar to my feelings at Damijan, the wine is a meal in itself. Overall, I find the Ribolla Gialla savory and, like its makers, stoic. The idea of a parallel cultural cuisine goes unconsidered in its production. The wines are not designed to be an accessory to a meal, making them more akin to marble statues than an agricultural byproduct. Aesthetic, structured and standing alone.

Mateja opens

the doors to the cellar at Gravner Estate.

Radikon

My visit to Radikon was highly anticipated. It is perhaps the most controversial macerated wine estate worldwide. When flaws regarding skin contact and natural wines are mentioned, Radikon is on the mind. In the United States, buyers in coastal markets fight over minuscule allocations of 500ml bottles to add to their selection—a true embodiment of cult status. Despite its rank, many in the industry are unenchanted by the rarity and think the wines are bad.

When I arrived at the cellar, the family was busy with travelers—something I had not seen at any other winery. Saša Radikon, the winery’s owner and operator, greeted me. Radikon took over after the passing of his father, Stanko. The Radikon family had and has some of the most profound ties to Josko Gravner, more than any other producer in Oslavia. Stanko Radikon had played a pivotal role in the early 2000s maceration boom. He stood next to Gravner the entire way out of intense loyalty, admiration and friendship. Radikon’s vineyards are farmed with sustainability at the forefront. Saša Radikon's smile while running his hands through the vineyards was infectious. He loves the land, the vines and his life.

After a walk in the vineyards, Radikon took me into the winery. It was rustic in the truest sense. The space was dark, the floors and barrels weathered, and moisture filled the air and ran down a grand wall of Ponca, forming stalactites. This was the first macerated winery I had been to that did not look like a showroom. The wines were almost all held or fermented in large, old wood. The air in the winery was thick. You could practically see it flowing in and out of the barrel's pores, making contact with the wine and then escaping. Topping off is not a common practice at Radikon. The grapes are left to express themselves in touch with the air.

I tasted a generous array of bottlings. Admittedly, I was slightly nervous to press Radikon about his challenging wines. Due to the unapologetic style, I assumed there was little room to discuss criticism. To my pleasant surprise, he had no issue discussing it. Radikon acknowledged and, in some instances, agreed that volatility had bested some wines in past vintages. Radikon mentioned that he has been and continues to make a concerted effort to produce more approachable and palatable wines for aspiring enthusiasts. That effort is on full display with the new RS bottlings.

Sasa

Radikon walks through the winery’s library collection.

Conceived by Radikon, the RS line is designed to be enjoyed at a younger age by producing wines with less skin contact and controlling oxidation more closely. The wines are also bottled in a more consumer-recognized size of 750ml, a deviation from the winery's historical commitment to 500 and 1000ml units. The willingness to adapt and capture more consumers was an unexpected twist in Radikon’s persona. I asked Radikon if he cared that many people didn’t like his wines. He very politely dismissed critics, noting they didn't have to. Radikon, like many other macerated producers, exports 70-80% of their production, while non-macerating producers average 15-20% exportation. Radikon feels confident in his ability to sell his wines, remarking that if every other market stopped purchasing them, he “could sell his entire production to Japan.” I learned that Japan has become a key center for natural and skin-contact wine distribution. It makes complete sense that macerated wines were more prominent in export markets than traditionally produced wines. Without domestic cultural ties, the wines are flown and shipped off to foreign lands, integrated with cultures that want to appreciate them.

At Radikon, I tried nine wines: a mixture of RS and main label bottlings: 2021 Slatnik, 2021 Sivi, 2018 Ribolla Gialla, 2018 O….., 2018 Jakot, 2008 Ribolla Gialla 3781, 2021 RS Rosso, 2007 Merlot, and 2011 Pignolo.

The RS whites are more approachable than the current release 2018 Ribolla, 2018 O…. and 2018 Jakot. However, I do not think they are a major departure from the brash style that carried Radikon to fame. The current release of the main label wines is the most challenging of the macerated whites. My nose often boxes against technical flaws to find some semblance of fruit or varietal character. Radikon acknowledged that drinking the wines too early could yield a… less-than-enjoyable experience. He was right. Age helped. The best white wine is the 2008 Ribolla Gialla 3781. With time, a more mellow set of aromatics plays out. Bruléed peach, pickled watermelon rind, fermented honey and slightly over-toasted walnut make kind introductions. The wine is not devoid of volatile acidity, but at least it is not center stage.

Like it or not, that is the house style. Radikon’s ethos is 'take it or leave it.' There is something to be appreciated about the distinctive nature of the wines, but how long will people overlook off-putting sensations and aromas in the name of low intervention and nature? Perhaps the creation of the RS line is partly an admission that it will not be for much longer. When wine becomes this cerebral, it can be difficult to envision enjoying more than one glass. A likelier scenario: sipping, assessing and reveling in its novelty for an hour, then placing the cork back to revisit later.

I would be remiss not to mention Radikon’s red wines. The 2021 RS Rosso and 2011 Pignolo are both fine wines, but the Merlot from the main label is the unsung hero of the lineup. The estate's winemaking finds a home with the grape. Like the white wines, the Merlot has many flaws, but it presents in a manner that is more intriguing than off-putting. I have had the pleasure of trying many vintages and have always found them captivating after a lengthy decanting to release some energy, displaying hoisin, balsamic reduction, desiccated black plum and cowhide. If you have an opportunity to taste an example from the early to mid-2000s, take it.

Paolo

Vodopievic outside of his home.

Vodopivec, Fiegl & Keber

I visited other wineries that produce and/or focus on macerated white wines. Paolo Vodopivec in Carso DOC is a notable example. Following in the path of Gravner, he too has a winery that appears like a movie set where he makes earnest and clean macerated wines. His focus is solely on Vitovska. The wines have pulse and verve and are worth seeking out for their approachable and classic style.

Kristian Keber also produces a skin contact wine from his holdings across the Slovenian border, separately from his family's production. In true Keber style, the wine blends Ribolla Gialla, Friulano and Malvasia. It’s a fun and energetic wine worth revisiting with age.

Lastly, Martin Fiegl, the acting president of the Associazione Produttori Ribolla di Oslavia, makes a skin contact Ribolla Gialla that is affordable, approachable and a relatively clean expression compared to his counterparts.

Art or Food?

After completing my tastings, I re-considered the critiques levied at macerating producers. Regarding the wines lacking terroir, I am largely in agreement. That said, the wines were never designed to tell the story of a place. As I mentioned, they were initially conceived as an experimental attempt to mask the story of their area's poor vintage. Of the wines I tasted, the style is the star, and the origin is an extra.

More curious is the tale of these producers’ philanthropic uplifting of Ribolla Gialla. These producers chose a grape that many wineries had written off for its lack of character as their champion varietal. Why? The grape, even when macerated, has no deeply distinguishable varietal character.

No lightbulb ever went off. I never started recognizing a ‘Ribolla Gialla quality’ in each wine. It became difficult to understand if this collection of producers truly felt that macerating was best for expressing Ribolla Gialla or if Ribolla Gialla was the quietest and most available grape to express their macerating. If you were to blind taste me on the Ribollas from Gravner, Damijan and Radikon, I could not find a common descriptor that denoted varietal character. I could, however—with certainty—note which wine belonged to which man.

Does

that make the wines any less consequential?

To me, it does not. It does, however, raise a question, one I posed to every producer on my trip:

"What makes a wine good, and can wine be bad?"

The knee-jerk response is, “Yes, wine can be bad.” Wine is “bad” when it is technically flawed to the point of being scientifically off-putting to the human palate. Wine is “good” when it has a sense of place, communicates to a culture and, most importantly, is consumed in its entirety. That answer is valid, thoughtful and, in many ways, true. If these were the objective parameters a wine needed to meet to be good or bad, almost every macerated wine I tasted would be bad.

I simply don't agree that they are.

The above sentiment is a fine thought progression if the wine is judged like food. But unlike food, wine is not just an agricultural product. It is the interpretation of an agricultural product. Wine appears more like art and less like a consumable when viewed through this lens. We accept art as subjective, and what is considered good art is not always pleasant or easy to digest. The macerated wines are produced like a painting—the grapes a pigment, and the winemaker their destiny-definer. As a finished piece, they tell the artist's story more than they do the origin of the materials. With the total context of the production trend in mind, I find it difficult to compare their quality to other wines in the area.

That is the point; these wines are solo acts.

An enclave of producers alienated (by choice or not) both culturally and viticulturally from their peers has no reason or incentive to contribute to the broader story of Friuli. The lack of cultural alignment calls into question the longevity of the category. As the bottles are exported and fawned worldwide, the wines are in danger of fading out of trend. Without a substantial culture to cling to and a challenging style, these wines have nowhere to go when the next cool thing globally comes along. If or when they do, macerating producers’ tense relationships with other wineries around them may become a glaring issue.

Views from inside Vodopivec.

Zooming Out

Many macerated producers noted tension and a lack of comradery with non-macerating wineries. It isn't easy to understand which side contributes more to the balkanization. Is the divide a result of disruptive winemaking or a larger commentary of a minority's resistance to assimilate? Moving forward, the rift between the two camps is Friuli-Venezia Giulia’s biggest and most inevitable problem. Individuals on both sides fuel and foster an environment of micro-disagreements that continue to keep their parent appellation from flourishing as a united front. A commonality could be achieved through the embracement of the region's diversity. However, unity can only be achieved if understanding and acceptance are practiced.

Large vs. Small

Macerating vs. Non-Macerating

Indigenous vs. International

Slavic vs. Austrian vs. Italian

Zooming out, Friuli is in a problematic state at large. Up close, individual factions have found success. With an eye toward the future, Friuli's messaging must become more cohesive. If mutual respect for each other’s choices can be extended, then Friuli will stand out as one of the most textured wine regions in the world. To accomplish this, all of Friuli’s disparate camps would need to do a lot of group therapy.

Friuli feels like looking through a kaleidoscope—beautiful and fragmented. If you stare too long, you will become disoriented and distracted from the fact that you are looking at a piece of art.

© 2024, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or re-distributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright, but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Friuli-Venezia Giulia: Both Sides of the Spectrum, Eric Guido, April 2024

Friuli Venezia-Giulia: In Search of an Identity, Laura Bruno, January 2024

Pride and Tradition: The Friulian Way, Eric Guido, April 2023