Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Treasures of Italy’s Southern Adriatic and Ionian Coasts

BY ERIC GUIDO | JULY 08, 2021

We look to northwest Italy for floral, nuanced reds that mix power with structure and poise. We turn to the northeast for richer, darker wines. In the center, we’re treated to the stimulating acidities, tart cherry-berry fruits and regal structure found throughout the Sangiovese belt. On Italy’s islands, we find a diverse mix of wines, yet all seem to take on a Mediterranean flair. However, it’s only in the south, along the bottom of Italy’s boot, where we find such a harmonious blending of ripeness, richness, power and sheer value. From whites and reds that provide early appeal and a pleasurable experience any night of the week, to wines that boast legendary structures that will carry them over a decade or more, all can be found from the heel to the toe and in between.

Harvest in the Titolo vineyard of Elena Fucci.

Calabria: The Original Enotria

While Calabria, the region that forms the sole, instep and toe of Italy’s boot, isn’t as prolific a producer of fine wines as most other regions, there is one DOC that is especially deserving of attention, and that is Cirò. The Cirò classico area is centered around the towns of Cirò and Cirò Marina, the entire growing zone runs down toward the Ionian coast from the foothills of the Sila Mountains. Cirò is produced primarily with the Gaglioppo grape, Calabria’s pride and joy, with its rich dark red fruits and spice, but also grippy tannins that require taming or long-term cellaring. In dryer years, such as 2012 and 2017, these tannins can come across as extremely harsh.

On the warm yet well-ventilated plains of Calabria, closer to the sea, Gaglioppo yields wines that are much easier to understand and might remind readers more of a fruit-forward Pinot Noir, though here it loses its gravitas. Traveling higher into the hills things change drastically, and you find wines of power, depth and longevity. Here the vines fight for survival, stressed for water on the sun-baked hills, yet they are balanced by the coastal influence of two seas and the dramatic diurnal shifts created by the Sila Mountains. The trick is achieving harmonious balance between fruit and tannins, which is best acquired through very gentle macerations and long aging. As an example ‘A Vita ages their Calabria IGT for two years prior to release, and their Cirò Classico and Superiore for three to four years. Unfortunately, not every producer has the resources or even the desire to deliver a more mature and palatable wine upon release, and many consumers are left scratching their heads over the severity often found from a current-vintage bottle. Even when released late, the wines are still structured.

When it comes to white varieties in Calabria, you can look to Greco Bianco (also found in Lazio, but different from the Greco of Campania). Greco Bianco is most often found in the form of Cirò Bianco, where it must make up at least 80% of the blend. To this day, the standard-bearer continues to be Librandi, a large producer that turns out over 200,000 cases of wine each year. I have no doubt that we will begin to see more of Greco Bianco, as many producers in Italy’s south have begun to understand the importance of their white varietals.

The historical “Storico” vineyard of Basilisco, with its eighty-year-old vines, located in Barile.

Basilicata: Up From the Ashes, But Will It Last?

We can’t talk about Basilicata, the arch of Italy’s boot, without focusing on Vulture. Of course, there are some excellent producers of Primitivo in Matera, closer to the border of Puglia. Vulture, instead, is famous for growing quality Aglianico (renowned for its role in creating Taurasi in Campania, a region that also borders Basilicata.) Volcanic soils run through Basilicata’s five delimited growing zones: Maschito, Ripacandida, Barile, Ginestra, and Rionero. Each of these locations is influenced by two seas bordering Basilicata on each side and a large range of altitudes and degrees of elevation, creating one of Italy’s greatest terroirs for Aglianico.

Vulture was placed on the map almost 50 years ago by a small number of great producers who breathed life into the region and understood how to properly market its wines. This renewed energy was felt throughout Vulture, spurring new interests and projects. Yet, with that initial surge in popularity came problems. Before long, dirty and lazy winemaking and the desire to make Aglianico’s inherent tannic clout more palatable through the overuse of new, yet often not very good, oak became rampant. Add a general sense of disorganization and a lack of clarity in communication and you have a recipe for disaster. That said, I firmly believe that today, Vulture is indeed producing world-class wines at a level that has never been seen before – but it hasn’t been an easy road.

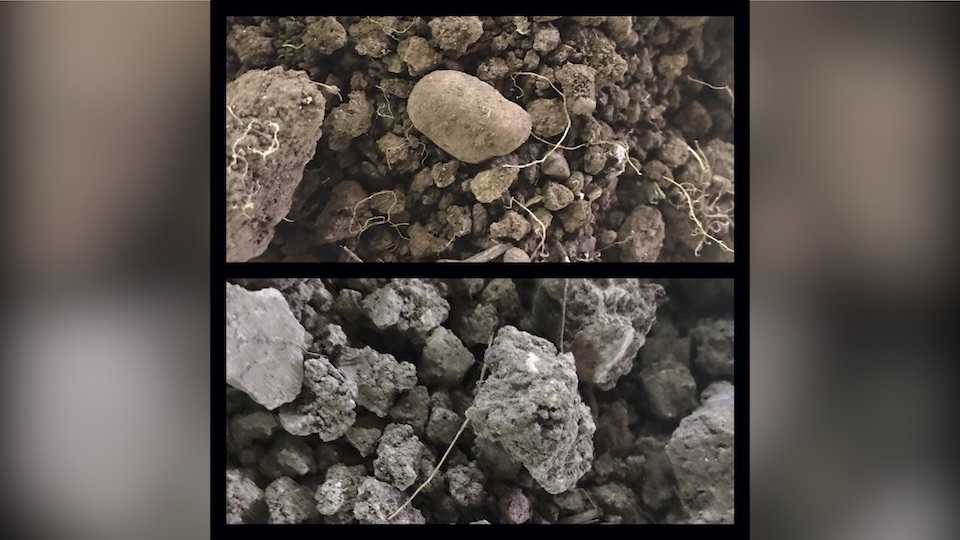

The diverse volcanic soils of Maschito verses Ginestra in the Grifalco vineyards.

My first serious introduction to the region was at a formal tasting seven years ago. Unfortunately, the wines were hit or miss. Out of a tasting of 23 wines, only three stood out. Most were large-scaled, some dirty, some reeking of oak, and often poured from bottles heavy enough to strain your wrist. I was encouraged to return to this tasting year after year, as producers were receptive to honest suggestions and opinions. Each time, I noticed steady progress in the right direction. A handful of quality-minded producers took on leadership roles out of their love for Vulture and its culture and history. The second year, I found cleaner wines and a much higher success rate; the third year, even more still, and suddenly an understanding from the producers that the names of the places and vineyards that the wines emerged from were important. In the fourth year, there were maps, satellite images and photos of vines taken within craters, and the poorly made wines were in the minority. Over the course of only a short time, a fine-wine movement had not only swept across Vulture, it had practically taken over – and it continues to this day.

Vulture is not out of the woods yet, and this article alone is evidence of that. The gathering of samples has been difficult, only a paltry collection of ten producers' portfolios were represented – luckily, some of the best. The good news is that an organized effort is underway to bring much deeper coverage to Vinous readers next year. Aglianico del Vulture will receive the respect it deserves, if for no other reason than that many of the producers are already creating wines that go beyond all expectations and still represent remarkable value.

Vulture continues to rise to the occasion.

Puglia: A Land of Unprecedented Value

Puglia offers a large and diverse selection of grape varieties to please many palates. When you add relatively low average prices and high quality often found in the bottle, it’s a wonder that more people aren’t drinking and talking about Puglia.

Located in the heel of Italy’s boot, Puglia is home to Primitivo. Wines made with Primitivo grapes from the Manduria growing region offer ripe, spicy intense fruit. These are reds that can be made in either a fresh and quaffable style or in a darker, heartier version, often with a dollop of oak. Manduria stretches along the coast (the inner part of the heel), where vines thrive on gently sloping plains that work their way down toward the water. This is a hot, dry part of Italy, moderated by the sea. While I’ve yet to find the depth of the best Zinfandels (both grapes are clones of the Croatian variety, Crljenak) being produced in California these days, many of Puglia’s top Primitivos aren’t far off.

Negroamaro, instead, is an herbal, earthy, and at times rustic, dark-red- or blue-fruited variety. In my opinion, Negroamaro doesn’t receive the respect or attention it deserves because of its own aromatic qualities that are oftentimes musky or volatile. This combined with its delicate yet sometimes sharp and tannic feel on the palate makes you think the wines won’t mature well over time. Looking at what Cosimo Taurino, Apollonio and Leone de Castris are doing with the variety shows that it can mature into a plush, earth-driven and floral red. I myself have begun to look to producer over location for the best source of Negroamaro. The Salice Salentino DOC is certainly a very good place to start, yet many good wines are produced under the much larger Salento IGT or the more localized Brindisi or Copertino. Negroamaro is also used to make interesting Rosatos with structure that permit short-term cellaring.

The third most important grape in Puglia is the lifted yet juicy, fruity, floral and spry Uva di Troia, also referred to as Nero di Troia. It yields wines that often possess the energy of a pretty young Beaujolais and the fleshy fruit of a southern Côtes du Rhône. It’s a mix that is quite pleasurable but also powerful. Traditionally, a very common blending partner for Uva di Troia would be Montepulciano, but today, we find pure varietal and truly exciting examples coming out of the Castel del Monte DOC. Other varieties worth mentioning and slowly gaining traction with producers are Susumaniello (now seen often in varietal form), Bombino Nero and Malvasia Nera; for a juicy white wine, try Minutolo or Verdeca.

A snowy Maschito vineyard shot, not long after harvest.

Burning Slow Versus Burning Bright: The 2018 and 2019 Vintages

Based on what I’ve tasted so far, 2019 looks like a promising vintage. Although turbulent weather and spring rains interfered with budding and caused late flowering, things turned around in June, gently pushing the growth cycle back on track. More rain arrived heading into July, which built up water reserves in time for the warm summer months ahead, yet never did the region experience any drastic spikes in temperature. Throughout the season, diurnal shifts between day and nighttime temperatures were ideal, keeping the fruit on the vines in perfect health. Due to the issues at the beginning of the season, quantities are down 10-15% throughout the boot. While most of the 2019 wines in this report were young reds and whites, I was able to taste the newly released Aglianicos from Elena Fucci, Grifalco, Cantine del Notaio and Macarico. If these wines are any gauge of the overall quality on Vulture, readers are in for a real treat.

A mix of Italy's sumptuous reds.

The 2018 vintage has proven to be a good vintage for Basilicata and Calabria. The year benefited from a cold winter with snow throughout December, February and even into March. This was followed by average springtime temperatures and a good amount of precipitation through April and May. On Vulture, rain lasted well into June, which is important, as the volcanic soils of the region absorb moisture deep underground and slowly release it to the vines during the hot summer months. September through October maintained warm daytime but also cool nighttime temperatures, with ideal diurnal shifts resulting in healthy harvests. The issue within Puglia came in the form of rain, which lasted throughout the harvest. I believe that 2018 will prove to be a slow-burn sort of vintage, especially on Vulture, where the wines will enjoy a long and broad drinking window, but never reach the heights of the best vintages.

© 2021, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or re-distributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright, but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Sicily: The Island Nation, Eric Guido, June 2021

Abruzzo and Molise: More Than Meets the Eye, Eric Guido, April 2021

Where the Wild Things Are: Welcome to Sardinia, Eric Guido, March 2021

In the Sweet Spot: 2001 Brunello di Montalcino, Eric Guido, March 2021

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Apollonio

- ‘A Vita

- Basilisco

- Bisceglia

- Botromagno

- Cantele

- Cantina di Venosa

- Cantine del Notaio

- Ceraudo

- Claudio Quarta

- Conti Zecca

- Cosimo Taurino

- Cupertinum

- Elena Fucci

- Giuseppe Calabrese

- Grifalco

- I Pastini

- Ippolito

- Koine'

- La Marchesana

- Leone de Castris

- Librandi

- Macarico

- Masseria Cuturi

- Masseria Li Veli

- Masseria Surani

- Masserie Pizari

- Matané

- Morella

- Musto Carmelitano

- Parco dei Monaci

- Paternoster

- Pietraventosa

- Polvanera

- Produttori di Manduria

- Rivera

- San Martino

- Santa Lucia

- Schiena

- Schola Sarmenti

- Statti

- Tenute Rubino

- Terre degli Svevi - Re Manfredi

- Terre dei Vaaz

- Tormaresca

- Trullo Flaminio

- Vigneti del Vulture

- Vigneti Reale