Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Mediterranean Spain: Where to Start?

BY JOSH RAYNOLDS | MARCH 18, 2021

The sprawling area of Spain’s Mediterranean rim starts in Catalonia and sweeps south and west through Penedès, Tarragona, Valencia and Murcia, then west to Andalusia. It also includes, for obvious reasons, the island of Mallorca. The range of wines produced from these sea-influenced zones is staggering, from bone-dry bubblies to structured, world-class reds and some of the most decadent sweet wines in the world.

The greater Mediterranean wine-producing area, especially Catalonia, produced a large number of outstanding wines in 2018, a vintage that tends to show noteworthy energy and balance. Some of the best wines from Spain’s eastern seaboard that I have ever tasted were made in 2018, especially from Priorat and all the way down to Valencia and Murcia. The warm to hot conditions that marked 2017 conspired to give many wines that show the darker side of the fruit spectrum and greater ripeness. That said, many excellent wines were made in 2017. Their heft and tannic structure should ensure positive aging potential. As for 2016, it was an outstanding year overall. Numerous wines are truly top-drawer, showing excellent balance and fruit intensity but seldom overtly ripe or marked dark fruit character. Two thousand and fifteen was also a fantastic vintage, producing wines of serious depth, power and structure with the requisite acidity to keep them lively and precise.

The terraced vineyards of Priorat are extremely difficult to work, but some of Spain's greatest wines are grown there.

Growing Seasons: 2018-2015

Two thousand eighteen has turned out to be a very good to outstanding vintage for regions across its Mediterranean rim. A dry winter was followed by a cool spring, with abundant rainfall, which was a relief as most of the area had been struggling with often severe drought conditions back to 2014. The weather was cool, so the fruit matured slowly through the summer, which was a very good thing for acid retention and keeping tannin levels low. Harvest began for most producers on the late side, as there were no heat issues that would have forced rapid or early picking. The resulting wines, overall, both reds and whites, show plenty of energy and bright fruit, with the balance to age but also expressive character that makes so many of them approachable, even now.

In contrast, 2017 was marked by hot, dry conditions and many of the wines show it. Fortunately for the growers there was a decent amount of rain in the winter so ground water levels were adequate, if not perfect. The spring and summer, though, were hot, sometimes very hot, not to mention dry. The vines struggled to produce fruit, especially young vines. Thanks to, or as a consequence of those conditions, most regions were harvested much earlier than normal, which meant that the grapes didn’t sit through a hot late summer and early fall, with their tannin levels building and their acidity dropping. Those low yields have given reds as well as whites that are on the concentrated side and often forward. But it’s not that simple. Growers who opted to hold off on picking, harvested ripe, sometimes super-ripe fruit, producing wines that show dark fruit character and solid tannic structure. This is by no means a homogenous vintage. For example much of northern Catalonia enjoyed a cool September. It was a year where the wines are defined by decisions made in the vineyards.

Two thousand sixteen has shaped up to be a consistently solid and often excellent year across the area. The winter was mild; the early part of the growing season was often cool and very dry, causing the vines to give lower yields than usual. A warm and often hot late summer accelerated sugar levels but not to an extreme, while acidity levels stayed healthy. Importantly, the berries were small in many cases, which gave the wines healthy concentration and, in the case of the reds, good tannic structure. At the same time there’s an overall energy to the best wines that have more than adequate structure and should age positively for many years based on their balance. The 2016s show less brawn and power than their 2015 siblings and should appeal to wine lovers who prize finesse and vibrancy over mass and brute force.

An outstanding vintage, by any measure and especially for those who like to hold their wines for long aging, 2015 checks all the boxes. Warm to hot weather, with little rain across the Mediterranean coast pushed ripeness along. Cool nights mitigated the heat and helped to keep acidity levels in check with the sugar levels of the fruit. Skins on the grapes were on the thick side so there are definitely tannins in the wines, but not excessively so. The best wines, and there are a huge number of highly successful examples, possess admirable depth and structure, which ensures that they will enjoy a long, positive evolution in the cellar. The fruit profile of the 2015s leans to the dark side, yet few wines come off as jammy or roasted.

Raventos I Blanc's family tree stretches back to 1497, and they are among Spain's elite sparkling wine producers.

Tarragona

The Tarragona DO is home to some of Spain’s most important winegrowing regions, notably the high-altitude Priorat, Montsant and Terra Alta zones. For eons Garnacha (spelled “Garnatxa” by many producers) and Cariñena (sometimes called “Carinyena” and also known as Samsó) have been the traditional red varieties grown here and, most likely, their original birthplace. Cabernet Sauvignon and to a lesser extent Merlot and Syrah were widely planted in the 1970s through the 1990s. Today many, if not most, of the top producers have shifted significantly away from those French varieties in favor of the traditional ones, a move that I enthusiastically applaud. It’s also noteworthy that more and more producers are moving toward using alternatives to small, oak barrels to raise their wines. Three hundred and 500 liters barrels and foudres, along with concrete tanks and clay amphoras are steadily becoming the rule here rather than the exception. As a result many of the wines show far greater purity than they did just a decade ago.

While Garnacha’s ability to produce outstanding wines in Tarragona has long been well-known, Cariñena, only really hits its stride when the vines are old. Vineyards planted to 50+ year-old vines are highly coveted and, no surprise, expensive. The small amount of fruit that is sold by growers who don’t make their own wine can be priced quite high as well.

Costers del Segre

Situated just west and slightly north of Barcelona, Costers del Segre comprises just over 4,000 hectares. It is increasingly being known as a source for high-quality wines. They are made from everything, from the traditional Catalan varieties as well as those from France, mostly Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Syrah, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc. Prices now, for the best wines, are slowly on the rise, but their quality is usually up to the tariff. The famed Torres family, of Penedès and Priorat, has taken a major stake here by establishing a 200-hectare estate, with vines planted on terraces, that’s focused squarely on bringing up the region’s reputation.

With 70 hectares of vines, mostly Garnatxa, the historic Cellers Scala Dei makes some of Priorat's most elegant wines.

Conca de Barberà

Located in the far northern, inland sector of Tarragona and due west of Barcelona, Conca de Barberà is another region whose overall wine quality has been on the rise in recent years. Most of the vineyards here are on relatively flat, gravelly riverbed soils left behind by the Segre river, which flows down from the Pyrenees, providing a good home mostly for Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot, such is the similarity of the terrain and dirt to Bordeaux. The wines here command quite fair prices for what’s in the bottle, especially compared to many New World renditions of Bordeaux varieties. They’re usually made in a forward, user-friendly style, although a handful of bodegas are pushing the envelope and issuing truly excellent wines that show real depth, complexity and the ability to age.

Cava, Outlier Bubblies and Penedès

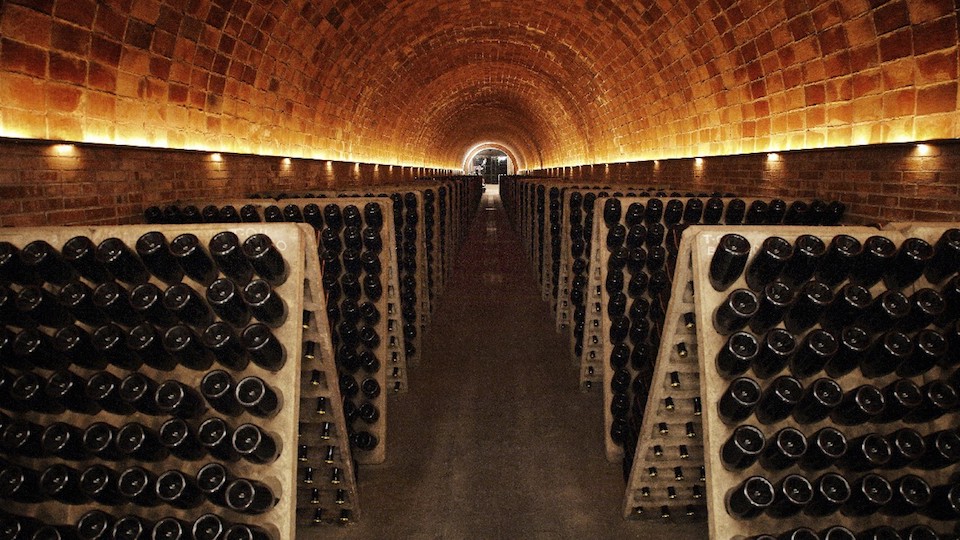

An increasing number of Cavas can now be considered truly outstanding. They are produced mostly from vineyards around the town of Sant Sadurní d’Anonia. Grape-growing is an old tradition here, dating back to at least the 13th century. A number of bodegas trace their family roots back to that period. Sparkling Cava began being made in the mid-19th century, quickly establishing itself as the favored wine style of the region. Today over 18 million cases are released to the market annually. The biggest chunk of it is, frankly, quite boring, if serviceable. Over the last two decades there has been a surge of producers whose intent is to bottle traditional-method, high-quality bubblies that deserve comparison to any sparkling wines in the world.

The local varieties, notably Xarel-lo (occasionally referred to as Pansa Blanca), Perelada and Macabeo (aka Viura and sometimes called Macabeu in the regional dialect), are the historic grapes of the region. These are the base for virtually all of the wines produced here. There’s also the rarely encountered Subirat Parent, almost exclusively used for making sweet Cavas. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir have established a strong foothold as well, while Monastrell, Trepat and Garnacha are grown usually with the purpose to make Rosé Cavas and occasionally still red wines.

More and more Cavas are being crafted in a bone-dry, Brut Nature style. The best producers are all dialing back their dosages, sometimes significantly, which is great news. These are far more vibrant, precise sparkling wines than those that were the rule a generation ago. At that time most Cavas in the export market were on the sweet, clunky and often coarse, rustic side. That did nothing for the region’s reputation. It has and will be an ongoing struggle to convince many wine lovers that Cava should be taken seriously. In response, a group of nine producers left the Cava DO in 2019 to establish a new category called Corpinnat. This requires the wines to be sourced exclusively from organically grown, hand-harvested grapes, to be made in the producers’ own cellar and to be aged in bottle for a minimum of 18 months before release. The trail-blazing Raventos family, of Raventos I Blanc, had already departed the Cava DO in 2012. While not a member of Corpinnat, Raventos’ wines bear the unofficial Conca del Riu Anoia designation.

Back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in many ways Penedès was the region that pushed Spain’s red wines into the international spotlight. Based on Bordeaux varieties but almost exclusively Cabernet Sauvignon, Familia Torres made a huge splash when their 1971, 1982 and 1985 versions of the flagship Gran Coronas Black label (now named Mas de la Plana) took top rankings when tasted blind, in high-profile competitions against some of the top wines of Bordeaux and Napa Valley. For most wine lovers at that time Spanish red wine meant Rioja, full stop. Many of the country’s other red wine-producing DOs hadn’t even been established yet or had minimal distribution, even if they had been producing serious wine for years. Plenty of people were shocked, hopefully pleasantly so, when they realized the massive potential that was at hand for varieties other than Tempranillo and for regions outside of Rioja. Today, Torres is still the pace setter here and, with large production and a worldwide presence, they are a highly effective leader of the zone.

Old bush vines of Monastrell, in Jumilla, produce some of the greatest red wine values in the world.

Valencia

The largest and best-known DO within Valencia is Utiel-Requena, which covers almost 35,000 hectares. It is perhaps best known as the ancestral home of the Bobal variety, producing the region’s best wines. Bobal makes up 6% of Spain’s wine grape production, placing it in a virtual tie for third with Garnacha and behind Airén (not exactly a well-known grape) at 22% and Tempranillo, at 21%. In the right hands Bobal can show real energy and complexity, while it is commonly used as a blending grape, to add dark color and acidity and also to produce grape concentrate for industrial wines.

Alicante covers just over 10,000 hectares also relying heavily on Bobal, mostly for simple wines. Monastrell, on the other hand, grows extremely well here. The best wines made from it can compete, in terms of energy and complexity, with top examples from Jumilla, the variety’s original home. There aren’t many of such wines being made just yet, but the success of a handful of producers, notable Bodegas Enrique Mendoza, will hopefully inspire others to follow suit. This small region is definitely one to watch.

Murcia

For red wines that deliver extreme bang for the buck Murcia is tough to beat. I’ll go far as to say that this is the best area in the world to find over-delivering red wines. So many impressive examples retail in the $10 to $15 price range. Relying mostly on the native Monastrell (sometimes referred to as Mataro, which is related directly to Mourvèdre), an increasing number of producers in the region are making wines that deliver uncanny complexity and sheer fruit impact for the money. Top bottlings can also age well but such is their forward charm that they are usually drunk up soon after release. It’s hard to blame those impatient imbibers.

Jumilla is by far the best known and the largest DO here, comprising almost 19,000 hectares. Monastrell rules the vineyards and most of the wines. Garnacha is also a player, producing some stunning bottlings as well. In the region Cabernet Sauvignon is also planted playing a role in some blends and occasionally bottled as a single varietal wine. While the most highly regarded wines have been experiencing price increase, the vast majority of Jumillas can still be had for a song in the $10 to $12 range (the Gil family and Bodegas Luzón’s are prime examples). The export market is thriving, making the wines easy to find.

With about 4,800 hectares under vine, Yecla’s wines are far less available as those from Jumilla and Monastrell is the dominant presence here. Monastrell in Yecla tends to produce muscular, concentrated and high-octane wines that can sometimes veer into over-ripeness if the producer isn’t careful. These can be rich, full-throttle and satisfying wines but they rarely match the finesse and complexity of those that are commonly found in Jumilla.

Andalusia

Málaga has for long-time well earned a reputation for its sweet Moscatels. It is an extremely difficult area to grow grapes or cultivate anything for that matter. Its extreme slopes spill quickly and treacherously down to the sea. As an obvious consequence, very little fruit is eked from these pampered, hand-tended, old bush vines. The wines produced represent some of the most decadent, complex and unctuous sweet examples in the world. Given the tenacity required to farm the vines and the pitifully small amount harvested, these wines deliver superb value compared to other late-harvest wines from around the world. They aren’t easy to find but they are absolutely worth the hunt.

The Tierra de Cádiz vineyards lie within the greater Jerez region and are mostly planted to what’s generically called Tinto de Cádiz, a catchall for dozens of indigenous and not yet identified red varieties. There’s increasing evidence that Graciano was a native grape here, before traveling north to gain fame in Rioja. That makes sense, as Graciano is naturally high in acid, as are almost all varieties in the Tinto de Cádiz family. The influence of the sea on these vineyards and often cool nights make for good retention of acidity. Many of the best wines show distinct freshness and cut, with their fruit leaning to red and vibrant character rather than towards the dark and brooding.

Of new interest are a small number of intrepid bodegas in Jerez as well as in Montilla-Moriles, experimenting with Palomino Fino and Pedro Ximenez to make serious table wines. Dry, usually innocuous white wines, raised in stainless steel tanks, have been produced here for some time. The newer versions are often aged in concrete or wooden barrels, with stainless steel making only an appearance; often a combination of all three. There are also some pretty wines that are being made after a brief time underneath a thin yeast cap, or flor, as with Sherry. They are bottled quickly to tame the yeasty influence and nutty character, but with enough aging to add great complexity. This is another category to watch, as the possibilities are intriguing. Early results, in their quirky way, have been mostly highly positive. Readers with adventurous palates, take note.

Mallorca

There are now just around 800 hectares of vines in the Mallorca Vi de la Terra DO. Production is, understandably, small. Most of the wines produced here are sold locally, which isn’t surprising given Mallorca’s status as a prime tourist destination for the well heeled. The best red wines tend to be based on or made entirely from the indigenous Callet variety, with the indigenous Fogoneu and Mantonegro, playing complementary roles. While dark-fruited, these reds emphasize energy and freshness rather than power, and tend to be relatively low in alcohol. Needless to say, tracking down the best examples can be tricky.

I tasted most of the wines in this report in New York during the winter of 2020/2021.

You Might Also Enjoy

The Vast Bounty of Central Spain, Josh Raynolds, February 2021

Mediterranean Spain: Diversity and Consistency, Josh Raynolds, April 2019

Spain’s Northern Regions Keep It Cool, Josh Raynolds, March 2019

Exploring Mediterranean Spain, Josh Raynolds, January 2016

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Acústic Celler

- Alberto Orte

- Albet i Noya

- Alta Alella

- Alta Alella-Celler de les Aus

- Altamente

- Altos d'Oliva

- Alvaro Palacios

- Alvear

- Ànima Negra

- Antonio Candela

- Atance

- Bodega La Viña - Anecoop

- Bodegas Abanico

- Bodegas Atalaya

- Bodegas Barbadillo

- Bodegas Bula

- Bodegas Care

- Bodegas Castaño

- Bodegas Crápula & Lanena

- Bodegas del Rosario

- Bodegas El Nido

- Bodegas Enrique Mendoza

- Bodegas Frontonio

- Bodegas Jorge Ordonez-Malaga

- Bodegas Juan Gil

- Bodegas La Cartuja

- Bodegas La Purísima

- Bodegas Luis Pérez

- Bodegas Luzón

- Bodegas Mas Alta

- Bodegas Murviedro

- Bodegas Mustiguillo

- Bodegas Niel

- Bodegas Nodus

- Bodegas Olivares

- Bodegas Ordoñez-Montsant

- Bodegas Orowines

- Bodegas Primitivo Collantes

- Bodegas Puiggros

- Bodegas San Dionisio

- Bodegas San Isidro

- Bodegas Sierra Norte

- Bodegas Sierra Salinas

- Bodegas Tesalia

- Bodegas Trenza

- Bodegas Volver-Alicante

- Bodegas Wineryart

- Bodegas y Vinedos El Sequé

- Bon Mas

- Botas de Barro

- Botijo Rojo

- Buil & Giné

- Can Sumoi

- Carmita

- Casa Castillo

- Casa Gran del Siurana

- Castell d'Encus

- Cava Llopart

- Celler Cecilio

- Celler de Capçanes

- Celler Mas Doix

- Celler Pasanau

- Celler Piñol

- Cellers Can Blau

- Cellers de Scala Dei

- Cellers Tarroné

- Cellers Unió

- Celler Vall Llach

- Cims de Porrera

- Clos Berenguer

- Clos Figueras

- Clos I Terrasses

- Clos Mogador

- Coca i Fitó

- Corasado

- Costers del Priorat

- DiT Celler

- Domini de la Cartoixa

- Edetària

- Ego Bodegas

- Escorlada

- Familia Nin-Ortiz

- Familia Torres

- Feixa Negra

- Fermi Bohigas

- Ferrer Bobet

- Finca Bacara

- Fuenteseca

- Genium Celler

- Gordo

- Hacienda y Viñedos Marques del Atrio

- Hammeken Cellars

- Heréncia Altés

- Heretat Mascorrubí

- Heretat Mestres

- Isaac Fernandez Selection

- Javi Revert

- Joan d'Anguera

- Josep Foraster

- Juvé & Camps

- La Bodega de Pinoso

- La Conreria d'Scala Dei

- Ladrón del Palacio

- La Vinya del Vuit

- Licorella Vins

- L'infernal

- Llenca Plana

- Ludovicus

- Marco Abella

- Maria Casanovas

- Mas Blanch i Jové

- Mascorrubí

- Mas d'en Gil

- Mas Gomà

- Mas Marer

- Mas Martinet

- Mas Sinen

- Mesquida Mora

- Mi Tractor Azul

- Naveran

- Paco Mulero

- Palacio Quemado/Alvear

- Perinet

- Portal del Priorat

- Raventós i Blanc

- Ritme Celler

- Señorio de Barahonda

- Temperamento

- Terroir al Limit

- Terroir Sense Fronteres

- Tocat de L'Ala

- Tomàs Cusiné

- Torelló

- Tranco

- Trossos del Priorat

- U mes U fan Tres

- Va de Bòlid

- Valdespino

- Vendrell Olivella

- Venus La Universal

- Vinos del Viento

- Vino Sexto Elemento

- Vinos Sin Ley

- Vins El Cep

- Viveros Cambra