Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Rescuing Memories: Philippe Gayral’s Vins Doux Naturels

BY NEAL MARTIN | OCTOBER 10, 2018

Wine is the Anna Wintour of the beverage world – it has always been fashion-conscious. Consider the widespread popularity of Sauternes amongst sweet-toothed Victorian oenophiles, even that old sugar lump Liebfraumilch during the 1970s that caused an entire generation of diabetes. Nowadays, fickle wine-lovers shun dessert wines and prefer to order an Uber than a cheeky Barsac at the end of dinner. No wine category has suffered an ignominious fall like Vins Doux Naturels (VdN): sidelined and forgotten about, virtually written out of history. VdN is the fashion equivalent of the lilac shell suit. Banyuls, Rivesaltes and Maury are veteran actors written out of the vinous soap opera; their characters not killed off in some end-of-series climax, but quietly starved of lines to read so that the audience never notices. In its heyday during the 1950s, more than 60 million litres of VdN was sold domestically, the favorite aperitif for middle class French women. Now production languishes below one million litres.

But you see, I have a penchant for sidelined and forgotten genres of fermented grape juice. Fashion is a circle. When something becomes so untrendy that its name cannot be mentioned in polite conversation without guffaws of laughter, then it has become the epitome of cool, like ripped jeans, cassette tapes and the boys’ name “Neal”. Ipso facto, Vins Doux Naturels is ice cold. Expect a sommelier stampede down to the Agly Valley any moment now.

And you need to start that stampede soon because one day it will be impossible to find mature VdN like the ones I am about to describe. The industry has withered dramatically in recent years, the nub dominated by co-operatives churning out commercial fodder for tourists who want a memento to gather dust in their drinks cabinet. Famous names that once produced immortal wines during the halcyon postwar period have disappeared or fallen into disrepair. Of course, there remains the excellent Mas Amiel, probably, the most high profile of producers, although their Maury production focuses more on recent vintages. To really discover the joy of VdN, you need to go back in time.

Philippe Gayral pictured in June this year at the London tasting.

Speaking of which, back in 2013 I received an invitation from Farr Vintners requesting my palate at a Vins Doux Naturels tasting tutored by one Philippe Gayral. I had never heard of him. Did I really want to give up my morning, tasting a wine that nobody cared about? Then again, I fancied dishing out desultory scores. Why not flex the 100-point system a bit? Could be a laugh...

That inaugural tasting was an epiphany. These time-buckling wines were absolutely delicious, occasionally profound in terms of complexity and nectar to the senses. How could I have been so naive, so wrong? Why were these wines not flying off shelves and why did nobody write about them? That was soon rectified with a series of pieces that I continue here on Vinous. I will keep expounding the virtues of these wines until my annual Vins Doux Naturels report attracts more traffic than Bordeaux en primeur (and the way en primeur is going, never say never...)

Remind Me, What Are Vins Doux Naturels?

Imagine a slightly timeworn estate of disheveled grandeur in let’s say, the Agly Valley in Roussillon, that has been passed from one generation to another. Down in the cellars under enormous ancient oak beams there is a team of laborers, country men with calloused hands and roll-up cigarettes in mouths, fathers and sons working amongst old wooden vats where through evaporation, angels take their share each year. The fortified wine might be transferred into small vessels unless topped up by another vintage (although only by 15% and once in its lifetime) and, perhaps, they end up in glass bonbonnes, baking under the sun. Over decades each wine will take its own course, some remaining rich and viscous like a Tawny Port, others drier and oxidative in style, not unlike Verdelho Madeira. It just depends on the amount of oxygen ingress over a long period of time.

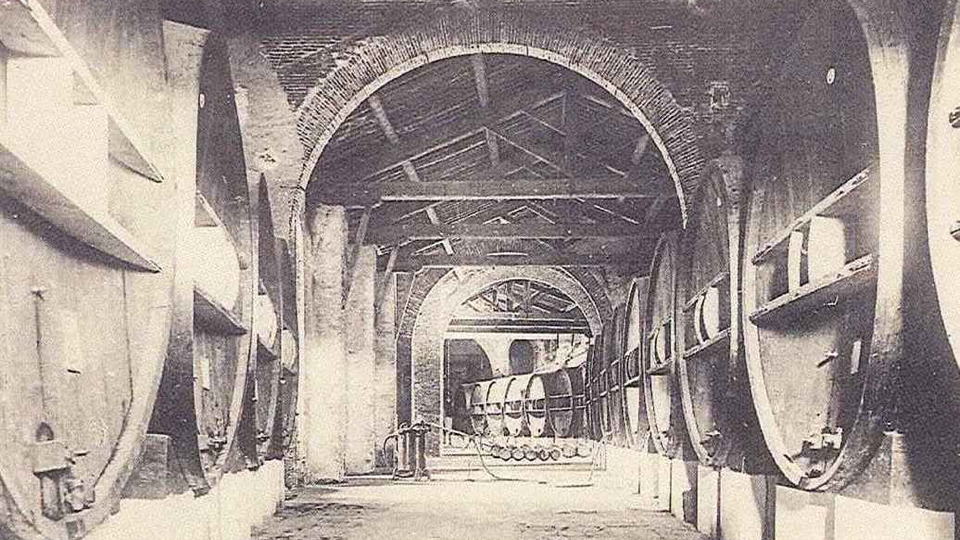

An evocative photograph taken at the co-operative in Maury, the exact date unknown - it probably offers a better idea of what this article is about than my verbiage. This is almost certainly the co-operative that is the source for the 1959 Maury to be released under Gayral’s L’Archiviste label.

Vins Doux Naturels are created by the addition of spirit in a process called mutage before the completion of fermentation, not dissimilar to Port although, generally, the wines are slightly less fortified and land at around 16°/17° alcohol. Gayral once told me that a famous doctor, Arnaud de Villeneuve, invented mutage in the 13th century, the same doctor who lends his name to one of the main universities of medicine at Montpellier. Today, many VdNs are based on Muscat d’Alexandrie or Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, though Gayral eschews the variety to focus exclusively upon the Banyuls, Maury and Rivesaltes appellations. Depending on the vintage, the optimal bottle age for these is around 50 years although my notes attest they can easily last longer. Gayral suggests that Rivesaltes needs a minimum of 20 years before the tannins soften sufficiently, while 30 years for Maury or Banyuls are optimal. I asked him to describe the differences between Rivesaltes and Banyuls...

“Banyuls and Maury consist purely of Grenache Noir and were traditionally made by small producers with small yields on schist terroirs, so they tend to be more concentrated and powerful and with more persistence and freshness due to the acidity. Rivesaltes tended to be produced by larger wineries and co-operatives and originated from vineyards planted with red, grey and white grape varieties of varying ages, often within the same parcel. The best VdNs are more complex than Banyuls or Maury. With Rivesaltes you find various styles of wine according to terroir and winemakers, whereas Banyuls and Maury tend to be more similar. In terms of production, at least prior to the mid-eighties, Banyuls and Maury are both more artisanal. They were often hand harvested and run by non-professional winemakers, doctors, postmen and fishermen and so forth. They would work from Monday to Friday in their normal day jobs and turn into winemakers for the weekend. Rivesaltes tended to be made by wealthier wineries working for the main brands of VdN such as Vabé, Manor, Rapha and Bartissol.”

The old vat-room of Domaine la Sobilane. Date unknown.

Gayral believes that Grenache Blanc and Grenache Gris, Torbato (known locally as Malvoisie du Roussillon) and Maccabéo are perfectly suited towards the dry, hot climate of Rivesaltes, especially around Les Aspres and Crest d’Agly. Here, he opines that Grenache Rouge would suffer from a lack of backbone. These wines are one of the few where white and red cohabit inside the same bottle, often around one-third of a blend consisting of white varieties to impart more complexity to Grenache Noir.

A Man On A Mission

Philippe Gayral is a man on a mission: to hunt down forgotten vats and barrels of Rivesaltes, Banyuls of Maury. He ostensibly rescues memories of bygone Roussillon, purchasing ancient barrels that pass muster and distributing them to a niche audience from the UK to the USA, Scandinavia to Japan. Gayral is an avuncular, self-effacing man whose main profession is teaching at French business schools and universities. He was in charge of the SICA des Vins du Roussillon co-operative from 1997 to 2002. Gayral then became the leading distributor of domestic VdN. During his buying trips he would stumble upon some unsold vats of ancient and, to all intents and purposes, mothballed wine. Invited to taste them, he was entranced by these abandoned lots, unable to comprehend the indifference towards them. “On one occasion, around the beginning of 1999, I was in the High Agly River near Maury. I discovered the proprietor had sold three barrels of excellent 50-year old Rivesaltes in bulk at the lowest possible price,” Gayral recalls. “On that day I resolved to save these wines from vanishing because they have witnessed history, from the First World War up to the 1970s.”

Over the last decade, he visited all the estates registered by French customs that were in possession of vintages older than 1975. “They were mainly unsold wines that were kept to improve other lots if necessary, known as “bonificateur”. Sometimes these lots were anniversary or kept for the birth year of a child. Occasionally the proprietor did not have a clue about the history of the barrels that nobody had touched for decades.”

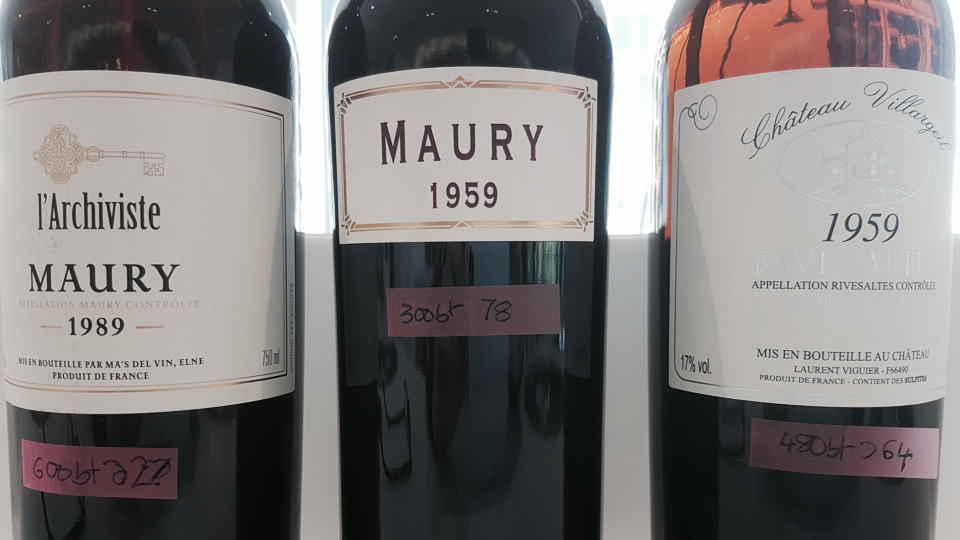

Bonbonnes, or glass demijohns, lined up under the baking sun to create Vins Doux Naturels. This is probably Domaine Pietri Geraud.

When I write that Gayral is saving these wines from extinction, I am not being glib. One of his most moving moments was at Château Sisqueille, which housed several barrels relating to various generations of the family. Before the Second World War, the property encompassed 2,300 hectares from Perpignan to the Mediterranean coast. Now the estate lies under tarmac as part of an affluent Perpignan suburb. Gayral bought the last remaining barrels days before Marie Sisqueille sold the château. She confided that she took solace from the fact that bottles would carry their name even though the estate was about to vanish. Readers will also see notes under the L’Archiviste label, which Gayral uses when the proprietor prefers not to divulge their identity or if he dislikes the name of the estate. Together with his wife, Sandrine, Gayral continues to produce young VdN, including one made with his friend Stéphane Gallet from Mas Amiel. “We decided to make non-oxidized style so that you can drink it sooner than traditional versions,” he tells me. “We have quite few wines remaining before the mid-1970s but much more from 1974 to 1985. Many of them are not yet bottled.”

I will give a short summary of some of the estates featured in this article, as I personally find them interesting.

Château Prieuré du Monastir del Camp

Allegedly, Charlemagne founded Château Prieuré du Monastir del Camp in 785 when he returned with his army from the Battle of Panissars against the Saracens, which explains why it was originally called “Monastry of the Camp.” Soldiers from Charlemagne's camp looked for a water source and built the priory where it was eventually found. A church and convent were built later, between 1090 and 1116. In 1786, just before the French Revolution, Louis XVI sold the estate to the Jaubert de Passa family, who remain owners to this day. They became one of the main Roussillon producers of wine, mostly VdN. After the Second World War, the present owner’s father decided to keep some wines as a “Réserve” for virtually every vintage, approximately 5% of the harvest except for bad or hail-affected vintages. Gayral chanced upon these 15 foudres or demi-muids spanning vintages from 1967 back to 1945. They are almost unique insofar that they show a complete collection of vintages from the same estate, offering a rare chance to analyze the influence of vintage on a single VdN. Gayral opines that they are emblems of great VdN during the 1950s, now considered the peak.

Domaine du Boaça

Boaça was first mentioned as far back as 876 as “villa buacano cum ecclisia sanoti martini” and records indicate that in the 10th century, wine and hydromel were produced on the same site. A 14th century castle was modified many times before finally being destroyed in 1974, whereupon the owner, Marquis de Boaça, decided to sell his whole property to a developer. Extant wines in oak foudres were then acquired by the “Co-operative of Canet en Roussillon” but since they were not that involved in VdN, they were simply kept in their vessels.

Château Mossé

Château Mossé is located in Sainte Colombe de la Commanderie, a former stronghold of the Knights Templar in the 11th century. The château itself was established in 1884 by the great-grandfather of the current owner, Jacques Mossé, in the foothills of Mt. Canigou, in a lieu-dit known as Aspres, which means arid or dry in Catalan dialect. The vines lie on very sunny slopes where the soil is chalk and schist, one of the best terroirs for VdN. After the First World War, Jacques Mossé’s father, Georges, began to maintain a reserve of barrels. From these, Gayral bottles the VdN, the vintages dating from the early 1930s up to the 1960s.

Château Villageil

Théodore Boubay, born in 1901 to a winemaking family, made the wines in the 1950s at Villageil. The red wines were bought by the cooperative while the VdN were withheld and vinified at home in a mixture of oak and concrete tanks, plus demijohns. In 1958, in the midst of the Algerian war, Boubay was too old to be conscripted. He stayed at the property and enjoyed a great vintage, keeping a proportion of the harvest back to tide him over for what he felt was an uncertain future. The VdN is a blend of Grenache Noir and Malvasie.

The Wines

The Vins Doux Naturels were tasted with Philippe Gayral at the offices of UK importer, Farr Vintners, and supplemented by a re-tasting of other vintages to form a comprehensive set of notes. I will not describe each wine individually, but offer my own general observations.

One of the major verticals was from Domaine la Sobilane, almost a complete run from 1969 back to 1946. They are one of the few that upheld quality well into the 1960s.

Firstly, there is no question that the sweet spot for VdN is the 1940s and 1950s, the postwar period when VdN was at its zenith. Therefore, most of the notes originate from wines made during that era, the passage of time allowing the tannins to soften and fascinating secondary aromas and flavors to emerge. Unlike many styles of wine, VdN is difficult to nudge in a particular direction during its drawn-out maturation. Each wine and, indeed, each barrel has a will of its own, charting its own evolutionary course depending upon the original wine, blend and vintage, more importantly, the level of contact with oxygen throughout many years sitting in a foudres, demi-muids or bonbonnes. Of course, the owner might transfer a wine from one vessel to another at any moment, thereby altering the trajectory towards a more or less oxidative style. Personally, I prefer the slightly more oxidative VdNs (readers should peruse the tasting notes for indications on this).

At its finest, VdN is a sweet fortified wine with irresistible red plum or mulberry fruit, traits of clove, stem ginger, marmalade, brown/Moroccan spices and dried orange peel. Most are quite viscous, though not to the same degree as say, a German Beerenauslese or particularly sticky Sauternes. Often the acidity cuts right through the richness to create wines that rarely feel heavy or fatiguing. Factor in the oxidation and you often end up with a fresh and lively VdN that forms the perfect denouement to a dinner.

My most recent tasting includes the 1959 Maury, one of the best of dozens of VdNs I saw with Philippe Gayral. It is scheduled to be released at the end of this year or early next year.

Intrinsic quality aside, I will repeat my assertion that hardly any category of wine matches VdNs for value. They are fairly indestructible, so in broaching old vintages, it is not like playing Russian roulette à la Burgundy. Crack a bottle open, you can leave it in the fridge and pour a nightcap over a period of time. I should also impress upon you that whilst VdNs are available and relatively inexpensive, this state of affairs will not last. I see Philippe Gayral every year and each time he warns that finding these hidden treasures inevitably becomes more and more difficult. At some point he will have mined everything findable and connoisseurs might look back and wonder why they did not grab a few bottles when they could. “Of course, it is harder and harder for the wines before 1975 to 1980,” he tells me. “I have about 550 cases in my collection from before 1975. Some will be kept for decades in order for next generation to have, “archives” to these rare and traditional wines. With respect to Château Sisqueille, the bottling was done 10 years ago and the wines are nearly all sold. I still have mainly Domaine La Sobilane and Château Villargeil. Everything from the 1940s to the 1960s has been bottled, likewise everything from the 1940s to the 1960s for Domaine Casenobe, Riveyrac and L’Archiviste.”

Of course, the question is whether modern-day VdN will reach the heights of those from the 1940s and 1950s. These days, wineries focus on recent vintages that appease an audience that wants to buy and drink today. Few producers or consumers volunteer to cellar such wines for a long time in order to create these decade-old Rivesaltes, Banyuls and Maurys, so their supply essentially ceased many years ago. There is no incentive. These older wines exist only because estates simply forgot about them or put them aside for their family anniversaries, birthdays and other special occasions. In an alternate timeline, Vins Doux Naturels would still be the favourite aperitif of sophisticated French women, restaurant customers would order a glass of Maury or Rivesaltes before the taxi home, and cellars around Perpignan would be replenished by selected barrels to be aged over decades for future generations to enjoy.

But fashion changed and modern day palates moved away from this style of wine. During the 1960s and 1970s, many co-operatives abandoned Vins Doux Naturels and shifted production to dry red wines. But trends do not strip a wine of the virtues that it was born with or acquired over many years of maturation. No other category of wine offers such a combination of deliciousness, complexity, history and affordability. Treat yourself...while you still can.

You Might Also Enjoy

Vintage Port – The 2016 Declaration, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: 1948 Taylor Fladgate Vintage Port, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira – Recent Releases, Neal Martin, March 2018

Cellar Favorites: 1870 & 1970 Centenario Colheita Tawny Port, Neal Martin, February 2018