Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Argentina’s Wines Enter the World Stage

BY STEPHEN TANZER | JULY 25, 2018

Against a backdrop of some recent tricky growing seasons and the constant economic challenge of doing business in Argentina, the country’s best producers are making more refined, aromatically complex and vibrant wines than ever before – bottles that should satisfy even hard-core fans of classic European wines.

My intensive tour of Mendoza during two warm, sun-drenched weeks in April allowed me to spend time with a number of the talented winemakers and viticulturists who have spurred the rapid improvement in Argentina’s wines in recent years. It also gave me another chance to investigate the spectacular terroirs of Uco Valley, which are producing a growing percentage of the country’s classiest wines. The city of Mendoza has witnessed tremendous growth in the new century, sprawling to incorporate nearby villages that were once outside the city proper. Getting out of downtown traffic and into nearby wine districts takes a lot longer than it used to. This is a bustling wine capital today, with new resort-style hotels catering to international tourists bearing stronger currencies. Where food in Mendoza was previously less adventurous and mainly suited for carnivores, far more diverse and ambitious restaurants have sprung up, with the relatively high prices charged by some of them making it clear that they cater mostly to tourists and wine industry visitors.

The timing for my tour in April, at the tail end of the 2018 harvest, was not exactly propitious. Despite the incontrovertible evidence of climate change and a number of freakishly early harvests in Europe since the beginning of the new century, Mother Nature has thrown some nasty curveballs at Argentina’s wine lands in recent years, particularly Mendoza. Argentina has suffered through a string of unusually wet years (2014 through 2017) and a couple of very short crops (’16 and ’17).

In the end, though, I should not have worried. My coverage this year, based on a combination of individual winery visits and group tastings, includes more 90+-point bottles than I have ever found in any past year – an accomplishment that’s only magnified by the fact that the quality of recent vintages has been decidedly uneven. Not only have the most conscientious growers and winemakers learned to deal with challenging weather, but some of the wines they have bottled from these vintages are simply more pleasing to those with European palates than wines from hot, dry years. And I tasted more new releases than ever before from the Uco Valley, which has become Argentina’s most exciting source of vibrant, lower-octane wines, with the best yet to come.

Early signs of autumn at the Zuccardi winery in Paraje Altamira

Uco Valley Is the Future, and Not Just for Malbec

Since the turn of the present century, the center of gravity in Mendoza has shifted southward from the so-called First Growing Region (Primera Zona Vitivinícola), the traditional heart of Argentina’s wine industry where quality wines were first produced on a large scale. This area includes the river bed of the High Mendoza River in Luján de Cuyo (i.e., the Las Compuertas, Vistalba, Agrelo and Perdriel districts) and western Maipú (Cruz de Piedra, Barrancas, Lunlunta and Russell), just southeast of the city of Mendoza and generally featuring flatter, lower-altitude vineyards than those of Luján de Cuyo a bit farther to the south and west. Wines from Luján de Cuyo in particular are best known for their structure and concentration, thanks in part to significant reserves of old vines. This area has long relied on an ingenious and extensive system of irrigation channels, some of them dating back to the 16th century, drawing on water from the Mendoza River, which in turn comes from the melting snow of the Andes.

Even the finest producers who originally established their operations in the First Growing Region have been expanding in recent years by acquiring and planting acreage in the Uco Valley, where vineyards are typically situated closer to the Andes and at higher elevation than the areas closer to the city of Mendoza (the better vineyards in Uco Valley are typically around 1,200 to 1,500 meters above sea level, vs. the ones at 600 to 1,000 meters closer to Mendoza). Led by such trailblazers as Nicolas Catena, the Michelini brothers, Clos de los Siete and its partners, Zuccardi and Salentein in the 1990s, the pace of planting in Uco Valley picked up in the early 2000s and is now a stampede.

Explosion of interest in the Uco Valley is as much a rediscovery as a new development.

According to Daniel Pi, head winemaker for the giant Trapiche firm, prior to the 1980s this region about 30 to 60 miles south and a bit west of the city of Mendoza was best known as a source of red blending grapes with strong color and tannins that were frequently used by producers in the First Growing Area (as well as in the regions of San Martín, Rivadavia, Lavalle and Junín on the eastern side of Mendoza – hotter areas that are known primarily for producing bulk wines) to add structure, color and acidity to their wines. But as domestic wine consumption in the local Argentine market began to shift from reds to whites and as Argentina’s economy collapsed in the late ‘80s, most of the old Malbec and other red grape vineyards were pulled out and replaced by orchards of apples, pears and peaches.

But in the mid and late 1990s, spurred by promotional low-interest rate plans offered by the government and a growing demand for Malbec from international markets, not to mention the arrival of new investors and wine consultants from abroad, plantings in Uco Valley began to increase again. Foreign capital was essential, as this area far from the town of Mendoza was also more expensive to farm and required serious investments in roads and infrastructure. Today, Uco Valley accounts for nearly half of Malbec production from Mendoza – as well as a disproportionate percentage of the country’s finest wines – despite representing only about 20% of the greater region’s total land under vine.

Water from melting Andes snow is critical to the success of vineyards here, and water rights are essential. Happily, recent wetter years have provided plenty of water, but future drought years will no doubt bring water shortages, especially as vineyard plantings continue to expand. For that reason, as well as to make better, more concentrated wines, an increasing number of vineyard owners have recently switched – or are in the process of changing – from flood irrigation to more precise drip irrigation.

Favored Soils and Sites in Uco Valley

Compared to Luján de Cuyo, for example, Uco Valley generally features a higher concentration of stony, more minerally soil, often rich in calcium carbonate (limestone is formed mostly of calcium carbonate), as well as a cooler climate overall, with wide day-night temperature variation making for good acid retention by the grapes. There’s less risk of hail here (although some higher parts of Uco Valley suffered hail losses in 2018), and the region’s sometimes-steep, high-altitude vineyards get very strong UV light, which produces thick-skinned grapes with considerable tannins. That’s a generalization, though, as the three alluvial cones that make up the region feature a wide range of soils. But the sites rich in calcium carbonate clearly yield more vibrant, perfumed wines with lower alcohol levels, healthier acidity, pungent saline minerality and balsamic qualities, and noteworthy flavor definition. Here you’re as likely to find red fruits as black, even in the area’s Malbecs. Uco Valley is the only part of Mendoza to offer some Winkler II growing areas (roughly equivalent in total growing season “degree days” to such cooler wine regions as Spain’s Rías Baixas and New Zealand’s Hawkes Bay), and in some recent vintages even Winkler I equivalents.

Favored districts like Gualtallary and Paraje Altamira, which are actually a good 30 miles apart as the crow flies, are producing some of Argentina’s most exhilarating, vibrant wines – bottles that will shatter the preconceptions many casual wine drinkers have about the Argentine wines and that are likely to age gracefully. But here, too, generalizations about soil, altitude and climate are useless. Gualtallary, for example, features more variation in vineyard altitude than Altamira, with one winemaker noting that temperatures in this particularly dry area “go from Napa Valley to Burgundy.” Indeed, Chardonnay has found a home in the area’s cooler spots, and numerous producers are excited about the potential here for Pinot Noir. Other closely defined districts, such as San Pablo just to the south of Gualtallary and El Cepillo to the southwest of Paraje Altamira and even closer to the Andes, are getting increasing attention from producers, not to mention from wine drinkers. Of course the best is ahead, as average vine age in Uco Valley is still quite young.

SuperUco's low-tech winery in Vista Flores

The Argentine Wine Industry’s Perpetual Economic Challenge

Repeated cycles of inflation followed by devaluation of the Argentine peso create a constant state of volatility, making it very difficult for producers to run profitable businesses and to plan for the future. As Paul Hobbs, a Californian who has been heavily involved in Argentina for the past two decades, not only as a producer, a consultant and a vineyard owner but as an importer of Argentine wines into the U.S. market, put it, “internationally, inflation squeezes a winery’s margin because the rate of increased costs in Argentina outpaces the rest of the world, making it impossible for producers to pass along those cost increases.” In fact, inflation in Argentina has averaged about 25% annually over the past five years. But to give you an idea of the volatility of the economy here, when I was in Argentina in mid-April, the U.S. dollar purchased 20.5 Argentina pesos. Less than two months later, a dollar bought 28 Argentine pesos. Imagine the difficulty of setting budgets under these conditions.

With inflation in Argentina, the cost of producing wine (including labor, dry goods imported from countries with stronger currencies or made locally with commodities whose prices are linked to the U.S. dollar, and grapes) goes up. Producers simply raise prices for their wines in the local market to keep pace with inflation but sales eventually slow as the local economy begins to suffer. Meanwhile, devaluation can make Argentina’s wines more competitive in export markets with stronger currencies– and even increase the level of promotional investment in exports markets, according to Sebastian Zuccardi – but this does not help producers’ margins. In any event, the advantages to producers can be short-lived, as the next bout of inflation continues the vicious circle. Vineyard owners who do not bottle wine are particularly squeezed, as the prices paid for their grapes are often insufficient to cover their farming and harvesting costs. Here, large producers who own their own vines and market their own wines are typically at an advantage.

There has also been a positive aspect to high inflation. Argentine wine sales in the U.S. market, for example, have been flat over the past several years. But while in normal circumstances this would drive export prices down as a way to incentivize importers, the high inflation rate has made it difficult for producers to use price as a mechanism for stimulating exports. This has kept retail pricing for Argentine wines stable, which in turn has had the effect of protecting the brand image of Argentina. Inflation has also prevented the emergence of a Yellowtail-like brand, which could have had an adverse impact on the image of Argentina wines.

Recent Vintages in Argentina

My mid-April tour of Mendoza took place during the final days of the 2018 harvest, and virtually everyone I visited was excited about this vintage, which brought high quality and copious quantities of grapes – the latter a huge relief after short crops in 2017 and 2016. The growing season was very warm and dry – a throwback to more typical weather for Argentine wine – so it remains to be seen which wineries are able to bottle wines with definition and energy. The harvest took place about two weeks earlier than usual. But, said at least one producer I visited in April, the large crop load may have constructively slowed down the ripening process and kept grape sugars from skyrocketing to dangerous levels. The red wines are generally described as intense, powerful and deeply colored, not to mention expressive. We shall see.

After 2016, the smallest and coldest vintage in Uco Valley in decades, growers were hoping for a larger crop in 2017, but spring frosts reduced ultimate yields, sometimes substantially. (More northerly regions like La Rioja and, particularly, Salta bucked this trend, producing healthy crop levels.) The summer was mostly clement – and not overly hot – and the small crop ripened early, benefitting from drier-than-normal conditions in February and March. The harvest started a couple weeks earlier than usual and only the latest pickers were affected by substantial rainfall in late March and April. The year was statistically a wet one, but much of the precipitation came in April, May and October. December and January were very warm and February was drier than normal, often requiring careful irrigation work to prevent a blockage of maturity in the vineyards. Quality-wise, the vintage appears to be very good, as the mostly early-picked fruit came in with good acid balance and concentration and considerable aromatic complexity.

A Succession of Vintages Without Extreme Heat

For years I have complained mightily about high-octane, overripe, low-acid wines from very warm, sun-drenched vintages in Argentina, often given a somewhat coarse character by distinctly unrefined tannins. But in fact, in contrast to so many other wine-producing areas of the world, Argentina has not had a classically hot growing season since 2012 – until the recently completed 2018 harvest, that is. So for several years running (particularly the 2014 to 2016 trio of vintages, the latter two – and especially 2016 – influenced by an El Niño weather pattern), cooked-fruit aromas and glaringly hot wines have been rare at the level of the bottlings I taste each year – and this is all to the good.

However, significant rainfall in ’14, ’15 and ’16 posed a stiff challenge for growers in Mendoza – not just to keep their grape clusters well-aerated but to know when and how to spray against mildew and botrytis and how to harvest vines with heterogeneous grape maturity. Several producers on my April tour mentioned that they made better wines in ’15 after having gained useful experience in ’14, and a few said the same thing about ’16 following ’15.

2016: A Challenging, Wildly Inconsistent but Sometimes Remarkable Vintage

Two thousand sixteen was disastrous in eastern Mendoza but often outstanding in Uco Valley, despite the fact that there was as much rain here as anywhere else in the greater Mendoza region. (In Altamira, where annual rainfall is around 250 millimeters, there were 760 millimeters between the flowering and the harvest.) Two thousand sixteen is a year that is impossible to speak about in general terms. The growing season was as far outside the norm as the atypically cool 2011 season was in eastern Washington State – and a lot wetter. A very snowy winter replenished water reserves and underground aquifers, but rains continued through spring, delaying the flowering by up to a month and leading some growers to fear a repeat of the disastrous El Niño growing season of 1998. Cool temperatures and precipitation continued from fruit set in December through March, which further slowed down ripening. Although producers had to spray repeatedly against mildew and incipient botrytis, the very cool temperatures through most of the summer had the effect of limiting botrytis pressures, particularly in Uco Valley and in other well-drained areas.

The year was generally very difficult in Luján de Cuyo and in other flatter, warmer sites farther from the mountains, particularly those on water-retentive clay-based soils. In these places the harvest was late but compressed, with the humid conditions facilitating the spread of rot. Doña Paula winemaker Marcos Fernandez described 2016 as “a difficult year, except for low-yielding vines on stony soil, which could get their fruit ripe enough.” But he added that there was a lot of botrytis and a strong influence of the cold temperatures at lower altitudes and so Doña Paula only kept their ‘16s from their higher sites. The late-picked Cabernet Sauvignon was especially problematic, and in some cases virtually unusable owing to underripeness, dilution or widespread rot. And lower, warmer, less-breezy sites on the eastern side of Mendoza were often disaster areas in 2016, with rot spreading quickly and most growers having to harvest their fruit before it fully ripened. Some even abandoned their vineyards, as the low prices they receive for their grapes could not justify the necessary investments in vineyard treatments and precise harvesting. Here only the strictest possible selection enabled some producers to make passable wines but often there was no usable fruit at all.

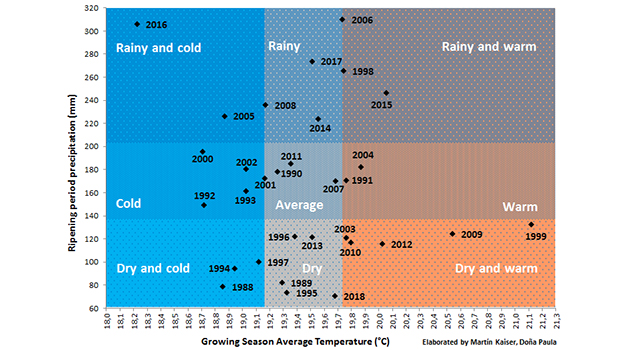

Argentine vintages by rainfall and temperature, courtesy of Doña Paula

But for many windy, higher-altitude vineyards on quick-draining, rockier soils, especially in the Uco Valley, 2016 has turned out to be a fascinating vintage – and not just for Malbec. (A few growers here told me that weather conditions improved later in the harvest.) Here the wines are also leaner and lower in alcohol than normal, but they show excellent intensity owing to the low yields, as well as considerable aromatic complexity and precision and firm structure. In fact, the best reds from the Uco Valley can be quite tight in the early going and give every sign of being eminently ageworthy. Many of these wines are in a distinctly “digestible” European style, and Francophiles who have always generalized about Argentine wines, considering them too ripe and high in octane, will be shocked by these bottles – in a good way. In addition to Malbec bottlings, some of the highlights of my tastings this spring were varietal Cabernet Franc and Malbec-Cabernet Franc blends from the Uco Valley and the 2016 vintage. And of course the cooler growing season of 2016 also yielded some unusually vibrant white wines.

As I mentioned last year, the flow of El Niño air in ‘16 was centered over Mendoza, so Salta far to the north and Patagonia to the south suffered much less from rainfall. Salta in particular had experienced sharp losses from spring frost and thus was more likely to have been able to bring its smaller crop loads to adequate ripeness, even under cooler-than-average conditions. In the end, production in the greater Mendoza region was down by 39% from 2015’s level (the regions of Salta and San Juan were also seriously affected) but Patagonia was virtually unaffected.

A Quick Look Back at 2015 and 2014

These two years were also much wetter than average. Two thousand fifteen, another El Niño-influenced growing season, was generally warmer than 2016 (and 2014). The growing season started off well but the early autumn and much of the harvest were plagued by rainfall, and the wines tend to be fleshy and fruit-driven. But again, steep, stony, well-drained vineyards in Uco Valley were less adversely affected by the precipitation and some growers reported that their wines had moderate levels of alcohol and sound acidity. It was a year that favored Malbec, as some of the late-harvested Cabernet, particularly on water-retentive soils, suffered from botrytis. Still, numerous producers maintained that they were better prepared in ’15 to combat the weather in both their vineyards and their wineries.

Two thousand fourteen was another cool, wet year but with lower precipitation totals than 2015 and, especially, 2016. The start of the 2014 growing season was not unlike that of 2015, but 2014 was distinctly cooler during the harvest period. Paul Hobbs noted that many Malbecs show good concentration despite the rains, but that the late-picked Cabernet Sauvignon suffered from dilution and botrytis. Hobbs did not produce any mid- or top-tier Cabernets at his Viña Cobos in ’14.

Susana Balbo emphasized that, in spite of differences among 2016, 2015 and 2014, all of these years were distinctly cool in the context of Argentina – “three Burgundian years in terms of degree days, with different results: you should expect more powerful wines in 2014, some inconsistency in 2015, and subtlety and precision in 2016.” She added that 2016 was the wettest of the trio and 2014 the least wet. (I should also note that Balbo views 2015 as a slightly cooler growing season than ’14, and she was not the only producer to express that minority opinion in April.)

Malbec Still Dominates in Export Markets

Malbec accounts for only about 18% of total vineyard acreage in Argentina but that number is a bit deceptive, as three of the country’s ten most widely planted varieties are the pink grapes Cereza, Criolla Grande and Moscatel Rosado, which as a group represent nearly a quarter of overall acreage, and a fourth is Pedro Ximénez. All of these varieties are mostly blended and/or used in the production of bulk or jug wines. Among other grape varieties better known to export markets, Bonarda (8.5% of total acreage), Cabernet Sauvignon (7%), Syrah (6%) and Chardonnay (3%) are the most important after Malbec. Mendoza is the principal source of Argentine Malbec, as it is home to 85% of the country’s total Malbec vineyard acreage.

Malbec continues to represent more than 50% of exports to the U.S., as well as the lion’s share of Argentina’s most exciting wines, but the variety is getting more and more competition today. I continue to be a fan of Cabernet Sauvignon in Argentina, particularly from favored classic areas such as the stonier parts of Luján de Cuyo, but also from what Paul Hobbs describes as “alluvial limestone-encrusted granitic rock” in certain parts of the Uco Valley. Cabernet Sauvignon inevitably improves when growers and winemakers take the grape more seriously. Owing to the commercial importance of Malbec, Cabernet has often been harvested after the Malbec crop was, in some instances practically as an afterthought. Certainly, Cabernet Sauvignon is a later ripener than Malbec (and it has had trouble ripening in recent cool, rainy years), but in many cases it was short-shrifted by being harvested too late, with fruit and tannins turning drier. This is no longer the case among the better producers.

Although many insiders believe that Argentina still has great untapped potential for Cabernet Sauvignon, particularly in the Uco Valley, in more recent years Cabernet Franc plantings have been growing at a faster rate, albeit from a much smaller base (still less than half of one percent of total vineyard acreage in Argentina). My tastings this spring indicate that Cabernet Franc has an especially bright future in Uco Valley – and not just as a blending grape.

![]()

The iconic Catena Zapata winery

Clearer Terroir Expressions, More Use of Concrete

Thanks in large part to the discovery and exploitation of favored sites in Uco Valley, there are more wines than ever before from specific growing areas, if not single closely defined sites. Today, single-finca (single-vineyard) wines comprise a disproportionate percentage of Argentina’s best new bottlings, and they typically carry price premiums as well. While stainless steel is still the preferred vessel for vinification (with the exception of numerous Chardonnays made in oak barrels), some producers are now using concrete receptacles of various shapes and sizes. Meanwhile, a growing number of producers, both modernists and traditionalists, have cut back dramatically on their use of small new oak barriques for élevage, opting instead to utilize larger neutral oak barrels and, increasingly, concrete containers – not just in an attempt to minimize the oak variable and preserve terroir character in their wines but also to bottle more vibrant, ageworthy wines. You will find many specific mentions of these developments in my producer profiles and individual tasting notes.

A Few Words on My Tastings This Spring and My Notes

I have attempted to maintain high critical standards in reviewing new releases from Argentina. As is my usual habit, I have provided tasting notes only for wines I rated 87 points or higher, simply listing other “recommended” wines that merited 85 or 86. But many, many more wines missed even this cut, for a wide range of reasons. Many simply do not possess enough material, whether due to excessively high crop levels, the difficulty of ripening fruit in rainy, cool years, or a combination of the two factors. Some wines lacked freshness, while others came across as downright weedy. Others are marred by heavy-handed use of oak (Argentina, like other southern Hemisphere countries, does not always get the highest-quality French barriques) – while some show gritty, drying tannins and little in the way of length. Of the many producers who submitted samples for my group tastings, a good 20 of them failed to make it into my coverage this year, as I did not rate any of their wines as high as 87 points. And with another group of the same size, I noted just a single new bottling.

Moreover, it quickly became clear to me during my visit to Mendoza that some wineries were reluctant to show their 2016s. So in several instances, I reported on ‘15s in my report last summer, while producers presented ‘17s, often just bottled, in April. Similarly, in a few instances producers skipped 2015 in favor of showing their ‘16s. In a number of these cases, I tracked down samples of missing vintages back home after my trip in order to fill in some gaps in my coverage, and to provide guidance on the vintages that are currently in the retail marketplace.

Argentine wine labels continue to be inconsistent when it comes to listing place names. In virtually every instance I have shown the most specific place name(s) available to me, but of course geographical indications are far less meaningful for wines that are blends from disparate sources. And my apologies in advance for small inconsistencies that I may not have caught in wine names. The large majority of my tasting this year was done in Argentina, and some wines for the local market carry labels that are slightly different from bottles earmarked for export markets. In many cases, this is just a matter of “reserva” rather than “reserve” but in some instances in the U.S. market, for example, label differences are more significant, often at the request of U.S. importers. So in many cases I have updated the information provided to me in Argentina to reflect the input of American importers regarding labels.

You Might Also Enjoy

Multimedia: Sebastián Zuccardi on Argentina's Uco Valley, July 2018

Argentina New Releases: Cool Times in the Desert, Stephen Tanzer, July 2017

Vertical Tasting of the Nicolás Catena Zapata 1997-2012, Stephen Tanzer, October 2016

Argentina: The Cool Years, Stephen Tanzer, March 2016

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- 2KM

- Achaval Ferrer

- Agostino Familia

- Aguijón de Abeja

- Alamos

- Alba en los Andes

- Alfredo Roca

- Alma Negra

- Alpamanta Estate

- Alpasión

- Altaland

- Alta Vista

- Altocedro/Karim Mussi Winemakers

- Altos Las Hormigas

- Amansado

- Ambrosía de Tupungato

- Andeluna Cellars

- Angulo Innocenti

- Antonio Mas

- Antucura

- Benegas

- BenMarco

- Bocanada

- Bodega Aleanna

- Bodega Amalaya

- Bodega Argento

- Bodega Atamisque

- Bodega Bressia

- Bodega Catena Zapata

- Bodega Chacra

- Bodega Cicchitti

- Bodega Cruzat

- Bodega Del Desierto

- Bodega del Fin del Mundo

- Bodega Del Rio Elorza

- Bodega del Tupun

- Bodega Elvira Calle

- Bodega Graffigna

- Bodega Iaccarini

- Bodega La Rural

- Bodega Malma

- Bodega Mauricio Lorca

- Bodega Noemía

- Bodega Norton

- Bodega Poesia

- Bodega Polo

- Bodega Raffy

- Bodega Renacer

- Bodega Rolland

- Bodegas Bianchi

- Bodegas Caro

- Bodegas de Arte Claroscuro

- Bodegas Fabre

- Bodegas Salentein

- Bodega Tapiz

- Bodega Vistalba

- Bodini

- Canciller

- Casa de Uco

- Casarena

- Casir dos Santos

- Chakana

- Cheval des Andes

- Clos de los Siete

- Colomé

- Corazón del Sol

- Corbeau Wines

- Crios

- Cuvelier Los Andes

- Dante Robino

- DiamAndes

- Domaine Bousquet

- Domingo Molina

- Doña Paula

- Don Rosendo Wines

- Durigutti Family Winemakers

- El Esteco

- El Porvenir de Cafayate

- Escorihuela Gascón

- Etchart

- Familia Cassone

- Familia Furlotti

- Familia Schroeder

- Finca Adrián Río

- Finca Agostino

- Finca Decero

- Finca Flichman

- Finca La Igriega

- Finca Las Glicinas

- Finca Sophenia

- Flechas de los Andes

- Gauchezco

- Gen del Alma

- Gouguenheim

- Goulart

- Graffito

- Grupo Foster Lorca

- Hacienda del Plata

- Huarpe

- Humberto Canale

- Kaiken

- Kalós Wines

- Krontiras

- La Celia

- Lagarde

- La Luz

- Lamadrid Estate Wines

- La Posta

- Los Clop

- Los Haroldos

- Los Toneles

- Luca Wines

- Luigi Bosca

- Maal Wines

- Manos Negras

- Marcelo Pelleriti Wines

- Marchiori & Barraud

- Mascota Vineyards

- Masi Tupungato

- Matervini

- Melipal

- Melodía Wines

- Mendel

- Mendoza Vineyards

- Michelini y Mufatto

- Miraluna

- Monteviejo

- Navarro Correas

- Nieto Senetiner

- Niven Wines

- Otaviano

- Pasarisa

- Pascual Toso

- Passionate Wine

- Piattelli Vineyards

- Piedra Negra

- Proemio Wines

- Pulenta Estate

- Puramun

- Revancha

- Riglos

- RJ Viñedos

- RPB S.A.

- Ruca Malen

- San Huberto

- Santa Julia

- Sin Fin Bodega

- SoloContigo

- SonVida

- Sottano

- Spielmann Estates

- SuperUco

- Susana Balbo

- TeHo/ZaHa

- Terrazas de los Andes

- Tiano & Nareno

- TintoNegro

- Trapiche

- Trasiego Wines

- Tres 14

- Trivento

- Underground Wines

- Vaglio

- Valle Las Nencias

- Vallisto

- Vicentin Family Wines

- Viña Alicia

- Viña Cobos

- Viña Las Perdices

- Wapisa

- Wines of Sins

- XumeK

- Zolo

- Zorzal Wines

- Zuccardi