Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Cave Spring Cellars Riesling CSV Vineyard 1999-2016

BY IAN D'AGATA | MARCH 12, 2019

I first visited Cave Spring Cellars in 1989 or 1990, and I’ve never stopped going back. It really couldn’t have been otherwise, as I’ve always liked the wine, the place and the people there. A little later, circa 1993 or 1994, my mother, who has never met a good restaurant she didn’t like, got in on the act too, and always seemed to have nothing to do when I was going to Niagara. We made a deal – provided we stopped for lunch at Cave Spring’s winery restaurant, she would do all the driving and I could drink away to my heart’s and stomach’s content. But Cave Spring Cellars’ significance goes far beyond personal memories. Founders Len Pennacchetti and Angelo Pavan (along with other historic Canadian wineries such as Inniskillin and Chateau de Charmes) helped kick-start the Ontario fine wine industry. The two were among the first in Canada to resolutely move forward with the planting of Vitis vinifera varieties, at a time when North American hybrids dominated local vineyards because of the belief that the country was too cold for European grape varieties to survive. Today, after over 30 years in the business, much-acclaimed Cave Spring Cellars produces world-class wines from the likes of Riesling, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc. And one wine in particular, the Cave Spring Vineyard Riesling, ranks with the world’s best in its category.

The beautiful Cave Spring Vineyard

How It All Started

If life had worked out as planned, Len Pennacchetti and Angelo Pavan, childhood friends since the age of five, would have never have become professionally involved with wine. Pennacchetti meant to be an Italian Renaissance history teacher (he earned a Bachelor of Arts from Carleton University in Ottawa and followed that up with a Master of Arts from the University of Toronto). However, he fell in love with wine early, thanks to the family heritage. His grandfather Giuseppe, who emigrated to Canada from the town of Fermo in Abruzzo to work as a mason, loved to tend to his vineyard of Vitis labrusca (a native North American grapevine) and make wine from it. His grandson Len (along with Len’s father, John Sr.) used to help Giuseppe prune the vines and in so doing developed a love for viticulture and vineyards. John Sr. successfully transformed his father’s lifework into a successful concrete business, and by 1973 was able to invest in the Niagara region. He bought farmland at Cave Spring, named by late-18th-century European settlers for its limestone caves and mineral springs. Thanks to its hillside location, warmer microclimate and clay-calcareous soils, Len and his father believed that this specific area had the potential to make wines that were likely to be at least a little bit better than Giuseppe’s hobby wine. They didn’t know it then, but they could not have been more right in their assessment. Today, their Cave Spring vineyard is located in the heart of the Beamsville Bench appellation (a sub-appellation within the larger Niagara Peninsula designated viticultural area or appellation of origin), arguably the best spot to grow grapes in Ontario, especially Riesling. In 1978, the Pennacchettis planted Riesling and Chardonnay, making Canadian wine history, as they were among the first to plant these cultivars in the region. In 1981, Len built a house on his property and began turning what had been a hobby and a passion into what would one day become his life’s work. Then, in 1986, Len joined forces with his lifelong friend Angelo Pavan, a former philosophy student with whom he had attended countless wine tastings over the years, and the two founded Cave Spring Cellars that year. As the two friends often like to joke, in the end it was really all a matter of “vino winning over Vico.” (Gianbattista Vico (1668-1744) was an Italian philosopher of cultural history and law and is considered one of the fathers of ethnology.)

Tom (left) and Len Pennacchetti (right), with Angelo Pavan in the middle

The Estate in Modern Times

The Cave Spring winery is housed in the stone and brick buildings that was formerly the Jordan winery (one of Ontario’s first, established in 1920), in the quaint, bucolic village of Jordan. Though small, the setting is absolutely charming and quaint, with some of the pretty buildings dating back to 1870. A stroll along the streets of Jordan is a walk back in time, and you’ll come away feeling like somebody dropped you into the middle of a Norman Rockwell painting. It’s also a great place to rest and relax after a long day of winery visits. Over the years, the Cave Spring Cellars enterprise has expanded considerably but remains a family-run operation. Len’s wife Helen, his brothers John Jr. and Tom, and the latter’s wife Anne are all heavily involved in the family business. John is in charge of business planning, while Tom (also a philosophy graduate, like Pavan) is vice president of marketing and sales; Anne (née Weis; her family owns the St. Urbans-Hof winery in the Mosel) is the manager of marketing and sales. Realizing the immense potential of Jordan, and believing that wine and food go hand in hand, Len and Helen decided in the 1990s to expand the business to include food and accommodations. And so it was that Helen first ran the estate’s absolutely outstanding On the Twenty restaurant (opened in 1993, it was Ontario’s first winery restaurant and started the regional food movement in Niagara), and then the Inn on the Twenty hotel, launched in 1996 (Twenty Mile Creek runs nearby). In 2003 a spa was added to the inn, and in 2005 the renovation of the Jordan Hotel and Tavern, a local historic landmark, was completed. In fact, Len’s and his family’s efforts on behalf of the town of Jordan and the immediate area did not go unrecognized; the Region of Niagara awarded Pennacchetti the 2007 Smart Growth Community Designer’s Award. Finally, last year, after more than 20 years, the family turned full circle, selling the inn and the restaurant in order to focus once again on the vineyards and the wines.

The quaint main street of Jordan village

Clearly, Cave Spring’s name, legacy and core business hinge on wine. The estate owns 66.5 hectares in two distinct sub-appellations of the Niagara Peninsula, the Beamsville Bench and the Lincoln Lakeshore. Roughly half of the estate vineyards (29 hectares) are planted to Riesling, followed by Chardonnay (10.5 hectares), Cabernet Franc (9 hectares) and Pinot Noir (7 hectares). The estate also grows Gamay, Gewürztraminer, Merlot and Sauvignon Blanc (in the past, it also grew the likes of Chenin Blanc; though the resulting wine was delicious, growing Chenin in the region’s cold climate proved a tough endeavor). Cave Spring Cellars uses almost exclusively estate-grown fruit, but does have two long-term relationships with local growers from whom they source and buy fruit to make wines (for example, they lease the Myer’s vineyard in the Lincoln Lakeshore). Over 80% of all wine made by Cave Spring is white wine, and half of that is Riesling; the estate makes seven different Rieslings at various levels of sweetness, including an Indian Summer Riesling (in the style of a Vendanges Tardives or Spatlese) and a Riesling Icewine.

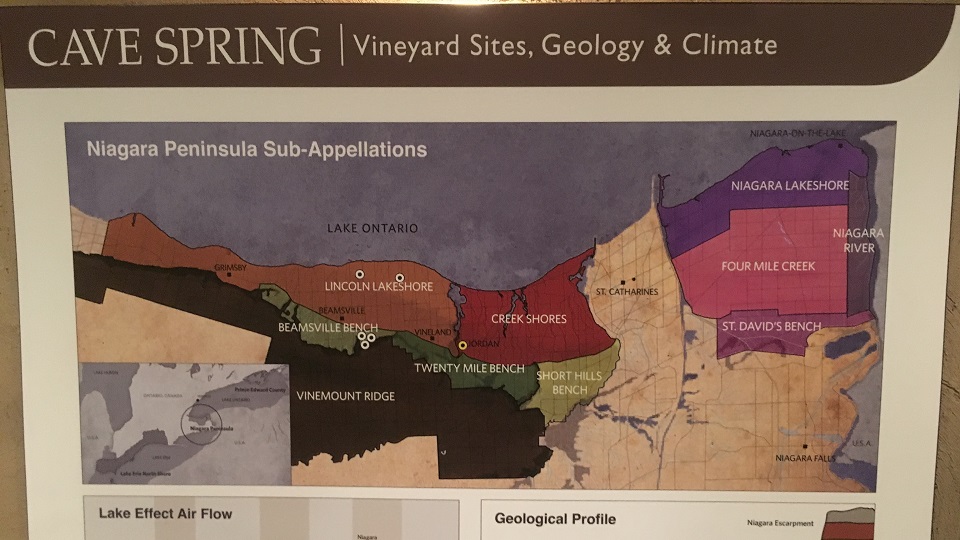

The Beamsville Bench and the zonation of the Niagara viticultural area

The Beamsville Bench and the Cave Spring Vineyard

The Niagara viticultural region has been the subject of one of the best zonation studies I have ever seen. The various Appellations of Origin and their sub-appellations have been extremely well defined on the basis of soil, exposure, growth degree days and other parameters, and there is a clear-cut correspondence between the wines made in each, as well as recognizable differences between similarly made wines from different sub-appellations. For example, the Rieslings of the Beamsville Bench are usually steelier, more mineral and more refined than those of the Lincoln Lakeshore, which are characterized instead by brighter, juicier and more forward floral and fruit aromas and flavors (especially peach). The Beamsville Bench is a gently sloping terrace situated between the Niagara Escarpment rising high behind it (the escarpment is a high mountain cliff that protects the vines from cold northerly winds) and Lake Ontario out in front, only three kilometers away (roughly 1.9 miles), so the vines benefit from the lake’s temperate breezes and its warming influence. The soil is essentially clay-calcareous (for precision’s sake, it’s a mix of escarpment limestone and dolostone, sandstone and shale rich in minerals with little organic content) that lies over moraine and sandstone/shale bedrock, and offers very good drainage. The combination of clay in the deep soil with the natural springs and escarpment water runoff ensures that soil water availability is always ideal in the Bench’s best sites (by contrast, other Ontario sub-appellations are characterized by thinner topsoil, and vines can suffer drought in hot dry vintages). Anyone fortunate enough to take a walk in the Cave Spring vineyard realizes immediately that it’s a remarkably beautiful, secluded, peaceful spot. In fact, it’s one of my favorite vineyards in the world. There is a magic in the place, with the old vines ringed by lush hardwood forests that contribute to the cool microclimate and help with retention of moisture, and there is a constant breeze blowing through, helping alleviate disease pressure in years of poor weather. It’s hard to explain, but standing there in the silence you just get the sense that those old vines can make magic happen.

And they do. The Cave Spring Vineyard (CSV) is 55 hectares large. It has always been a superb spot in which to grow Riesling; in fact, no less a grape-variety-lover than Randall Grahm, when visiting Cave Spring more than 20 years ago, told Pennacchetti and Pavan that Riesling should be their calling card. “Having someone like him say that certainly gave us a huge boost in confidence, at a time when everyone around us was still leaning towards hybrids,” smiled Pavan. “But you know, it was really tough going. It meant standing by our faith in vinifera varieties and holding the course steady even in the face of great adversity, such as the winter kill of 1980 (on Christmas Day, temperatures plunged to –26°C [–14.8°F], damaging many vines all over Niagara). Interestingly, though, we found that Riesling handled that cold spell admirably, thereby reinforcing our conviction that it was the right grape to grow here.”

The Cave Spring Vineyard's unique microclimate, situated in a small clearing in close proximity to the woods

In the beginning, Pennacchetti and Pavan didn’t plan on making a single-vineyard Riesling. Pavan’s trip to the German wine regions in 1999 changed that. After visiting the likes of St. Urbans-Hof, Schloss Vollrads, Bürklin-Wolf, Selbach-Oster and other then-venerable German estates, he started thinking that he too should be making a single-vineyard Riesling. It was, after all, the many fantastic old specific vineyard wines Pavan tasted at the different estates he visited that left a lasting impression and made him want to try his hand at making a similar wine. “I remember tasting a fantastically good 1969 J.J. Prum Wehlener Sonnenuhr Auslese that had me thinking it was eight years old. I couldn’t believe it when they told me it was actually 30 years old! At that time I was making Rieslings back home that could age 10 years, but tasting those German beauties got me thinking that we might also be able to achieve similar ageworthiness in Niagara. And so I started focusing on making a single-vineyard wine that later turned out to be our CSV Riesling. I targeted the single blocks of oldest vines we owned and reduced crops even further to see if I could come up with something special. Luck was on my side, as well as a great vineyard.”

A portion of the CSV’s vines are among the oldest vinifera vines in Canada, planted in 1974 and 1978. Only 5% or so of the vineyard’s best grapes are used to make the estate’s CSV wines (besides the Riesling, there is also a CSV Chardonnay), and these CSV wines are made only in the best vintages. The Riesling CSV is made from the two oldest blocks of vines (ranging from 40 to 44 years of age; one block is the original set of vines planted in 1978, while the other, only 30 meters removed from the first and bought by Pennacchetti from a neighbor in 1996, also boasts very old Riesling vines, planted in 1974 and 1978); in some vintages, grapes from a third, slightly younger, block are used too. The Riesling is planted on mostly SO4 rootstock at an altitude of 135–160 meters above sea level. The orderly rows of vines are oriented north–south, spaced either 0.9 or 1.2 meters between vines and 2.25 meters between rows, with branches bent left and right of the main trunk (in order to reduce Riesling’s natural tendency for apical dominance). Pavan chooses to press his grapes softly with an overnight skin contact; he ferments at 16–18°C, and the fermentation can last anywhere from three to six weeks, depending on the vintage. Pavan has been using indigenous yeasts for the past eight years or so to make the CSV Riesling (by contrast, the more entry-level Rieslings of the Peninsula and Escarpment lines have been made with large portions of indigenous ferments only since the 2015 vintage). Fermentation takes place in stainless steel tanks, and the wine spends roughly five months on the fine lees prior to bottling. Until recently, Pavan has aged the wine in stainless steel, but he has begun experimenting with large oak barrels (such as old 500-liter puncheons); as of the last five vintages, about 20% of the total wine blend is aged in wood.

In my experience, Ontario Rieslings fall squarely between those of Germany and Australia: more structured and tropical than the former, but more graceful and less marked by herbal/diesel notes than the latter. In particular, the CSV Riesling often showcases notes of fresh citrus (especially lime and pink grapefruit) and yellow plum; in warmer vintages, more exotic fruit notes dominate. With age the wines develop a very recognizable note of licorice or anise. Cool-year wines are especially juicy and vibrant, and though a steely mineral, flinty undertone is always present, outright diesel fuel nuances are more apparent in warmer vintages (such as 2002 and 2007).

The wines in this report were first tasted in July 2017 at Cave Spring Cellars along with Angelo Pavan and Len and Tom Pennacchetti. Having bought the CSV Riesling from its very first vintage, I replicated the tasting in Rome in May 2018 with bottles sourced from my own cellar and purchased upon release, adding the 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009 and 2004 vintages for a more complete vertical.

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

Norman Hardie Chardonnay Vertical: 2006-2014, Ian D'Agata, November 2016

Canada’s Maritime Provinces: A New Wine Frontier, Ian D'Agata, October 2016

Tawse Chardonnay Quarry Road: 2006-2013, Ian D'Agata, August 2016